American Literature: Our Own Neglected Canon

- ELIZABETH KANTOR

One notable thing about American literature is that, for such a big country, weve specialized in small literature.

|

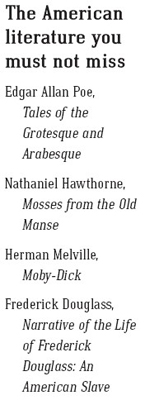

American literature is not Allen Ginsberg, Toni Morrison, and Dan Brown. PC English professors naturally gravitate toward American writers who share their disdain for America, Western civilization, and Christianity. But our best literature combines what’s uniquely American with what’s of universal value. While it has to be admitted that America has not produced a really world-class literature, there are American writers who have much more to offer than anti-Christian paranoia, victim ideology, and the clichéd incoherence of the Beats. A few of our writers have created really important literature—literature that’s worth anyone’s time and attention, and that we, as Americans, should know.

![]()

Big country, short attention spans

One notable thing about American literature is that, for such a big country, we’ve specialized in small literature. Two of our three greatest poets (Robert Frost and, even more so, Emily Dickinson) are known for their fine short works. While twentieth-century American critics and writers developed a sort of obsession with “the great American novel,” our best fiction is almost all short.

American writers have had big ambitions, but attempts to create monumental works often haven’t turned out as well as projects of limited scope. In the nineteenth century Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and the other “fireside poets” turned out reams of workmanlike but mostly second-rate verse. And Walt Whitman wrote his sprawling Leaves of Grass, a collection of poems that add up to a kind of epic of the selfaffirming ego. These include the well-known “Song of Myself,” “I Sing the Body Electric,” and “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed”— the elegy for President Lincoln that, in Joseph Bottum’s telling phrase, “spreads Whitman like margarine across the nation.” There’s wheat in Whitman’s poetry, but there’s plenty of chaff there, too.

|

|

Meanwhile, Emily Dickinson was writing her tiny jewel- (or dagger-) like lyrics. Ezra Pound’s epic-length Cantos are impossible to follow; some of his shorter poems—especially “The River Merchant’s Wife: A Letter”—are deeply moving. Edgar Allan Poe went so far as claim that there was no such thing as a long poem.

We’ve got a big country, but we’ve got short attention spans. If “the great American novel” has to be epic-sized (to match the wide open spaces of our country) then Moby-Dick is the obvious choice. But it’s a sort of standing joke—Woody Allen built a feature-length film around it— that hardly anyone actually reads Melville’s huge novel all the way through. Hawthorne’s stories are wonderful, and his novels get longer and longer, but not better and better. The Scarlet Letter, early and short, is the best; The Marble Faun, the last and the longest, is the worst. Henry James’s novels aren’t American enough to qualify—he lived in Europe and England for most of his adult life. And Faulkner is so very regional that it’s hard to think of his novels as embodying the American experience. All things considered, the top contenders for “the great American novel” have to be two very short books: Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. The short story, not the novel, is the quintessential American literary genre.

Maybe our attention spans are short because the American experience is less about perseverance than it is about fresh starts. Whatever the European discovery of America meant for the American natives, for Europeans it meant a chance to start over again. Landless younger sons and transported debtors, religious dissenters seeking to establish a society according to the dictates of their consciences, artisans looking for better compensation for their work—all these folks could get a second chance in America. And some of them got a third, and a fourth. America was a big, open place: it was much easier, here, to leave your mistakes behind you and start again.

It’s a fascinating question, what a fresh start can do for you, and what it can’t. The awareness of the frontier always out there had some wonderful effects on the American character. It seems to have protected us from the cynicism that’s the prevailing note in the modern European character. But you can’t always solve your problems by getting away from them. As the psychologists point out, you can leave your job, or your hometown, or your marriage—but you always take yourself with you. Americans have continually had to realize that fact, and the best American literature explores that discovery.

![]()

The mystery of evil

The great theme of American literature is the mystery of evil. Here we are, on a brand new continent. We left our problems behind in our past, when we freed ourselves from the yoke of the despots of Europe. We established a truly righteous society of Christian saints. Or at least we escaped our troubles by leaving New York for Missouri, or Iowa for the Dakota Territory. Or if evil wasn’t behind us, it was out there somewhere—in the wild woods with the Indians, in the forces of nature we had to contend against to cross the wide new continent, or in the vastness of the untamed ocean.

But the continually renewed insight of great American literature is that evil is not just “out there,” and you don’t leave it behind when you move on. Cruelty and suffering will keep reappearing, and their existence can’t be forever blamed on the clinging corruption of the old things. One great work of American fiction after another dramatizes the (always late, always surprising) discovery that evil is really here, inside us, in the human heart. As William Faulkner explained in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, the only things worth writing about are “the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself.”

In Moby-Dick Captain Ahab pursues the great white whale, which cost him his leg, across the untracked ocean, as if one wild beast were the locus of evil in the world. But it becomes obvious that the real evil is in Ahab’s own self-destructive obsession.

Edgar Allan Poe’s stories plumb the extremities of sin and crime to which human beings will sink, and explore how their crimes transform them. “The Cask of Amontillado” focuses on the act of murder itself: we watch the narrator carry out a particularly exquisite act of revenge on his enemy. “The Tell-Tale Heart” concerns itself with the murderer’s guilt, the only thing that keeps him from getting away with his crime.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s works are also about sin and guilt— The Scarlet Letter , of course, but also dozens of stories. “Young Goodman Brown” is one of the best. No murders are committed—in fact, Hawthorne leaves it unclear whether anything worse than a walk in the woods actually occurs. The story is set in early colonial Massachusetts, when Puritan rectitude was still the general standard.

As the story begins, Goodman Brown is bidding goodbye to his new wife, Faith, as he sets out on a journey. It’s obvious that he’s doing something he shouldn’t: “What a wretch I am,” he says to himself, “to leave her on such an errand. . . after this one night, I’ll cling to her skirts and follow her to Heaven.” He travels through the woods, wondering whether “a devilish Indian” may be “behind every tree,” or “the devil himself” “at my very elbow.” Pretty soon the Devil does show up, and it’s clear that the young man has arranged to meet him in the woods.

|

Goodman Brown almost turns back, but the Devil persuades him to talk things over. He has an answer for the argument Goodman Brown has fastened on for going home: “My father never went into the woods on such an errand, nor his father before him.” But they did, the Devil assures him—and gives examples of actions he claims to have inspired in the young man’s ancestors. Goodman Brown is further disconcerted by the appearances of several of his respected elders along the forest path, whose appearance helps wear down his powers of resistance.

The one last sure thing Goodman Brown clings to—the goodness of his wife—is torn from him when he hears her voice above the woods. “There is no good on earth;” he decides, “and sin is but a name.” Maddened, Goodman Brown rushes toward the place of initiation, where he sees Faith, like himself, a convert waiting to be baptized into the satanic church. Once they’re marked by the Devil, they’ll be privy to each other’s secret sins. “What polluted wretches would the next glance show them to each other,” the young husband wonders, “shuddering alike at what they disclosed and what they saw!” Just before the deed can be done, Goodman Brown cries out to his wife to “look up to Heaven, and resist the wicked one.”

He never knows whether she obeyed his warning. The instant Goodman Brown cries out, the Devil’s church vanishes, and he finds himself alone in the woods. Goodman Brown’s last-minute refusal can’t save him entirely from the consequences of his experiment with evil. He can’t know for sure whether the forms he saw in the forest were illusions of the Devil, an ugly dream of his own, or the real shapes of his teachers, neighbors, and wife. But the fact that he saw them changes the rest of his life. Goodman Brown sees hypocrisy and secret wickedness behind all the piety and humble happiness of his Puritan village. He’s apparently avoided the Devil’s baptism, but he’s cursed with the belief in—if not the actual knowledge of—his fellow man’s wickedness. His suspicions poison everything for him; he dies an embittered and hopeless old man.

There’s good psychological insight in Hawthorne’s story, which has special resonance today, when there’s an online community for every perversion devised by the mind of man. The knowledge, or even the suspicion, that others share your secret sin undoubtedly weakens your own resistance to it, for exactly the reasons Hawthorne sets out in his story: the community of co-conspirators is attractive, and its existence makes virtue and innocent happiness seem like illusions.

![]()

The possibility of escape

The mystery of evil continued to exercise the American imagination as the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth. After the frontier experience came to an end, Americans found new places “back there” or “out there” in which to locate evil. The capitalist robber barons were the problem. Or the trouble was the bankers back East: Mankind was being crucified on a cross of gold. Or, on the other hand, our progress toward a well-ordered and healthy society was impeded by trashy riffraff who overburdened our new social services, and whose out-of-control breeding had to be gotten under control.

But increasingly, in the twentieth century, the locus of evil was thought to be culture itself—not just the European past, with its corrupt monarchies, but the very existence of a civilized tradition, felt as the dead hand of the past weighing on the present. The traditional conventions and expectations of society (whether of the old New York families in the Social Register, or of the neighbors in a small town in the Midwest) were felt as an intolerable burden. Americans would shake free of this stifling inheritance. We would shake off tradition and invent new, scientific ways of solving social problems and educating future generations.

All these different strains of thought left their marks in the American literature of the twentieth century. Happiness seems to be impossible without some kind of escape—whether from the neighbors or from the past. Edith Wharton’s novels paint life among the old New York families as a stifling trap; Sinclair Lewis’s Babbit and Main Street do the same thing for middle class life in Middle America.

|

Hemingway’s heroes are always on the run from something (which might just turn out to be themselves). They’re on their own, out in the wild, hunting or fishing. Or they’re serving in foreign wars. Or they’re Americans abroad, living in Europe—anywhere they might be able to hold together an integrity that’s somehow impossible under the conditions of ordinary civilized life in their native America. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is about the emptiness at the heart of the American dream, the futility of the never-ending quest—“tomorrow we will run faster, stretch our arms farther”—for a happiness that is already lost in the past.

|

Interestingly, the most successful regional American literature is the product of the part of our country with the most stifling, tradition-fraught culture. The South has always been the most backward-looking and Anglophilic part of America. It was for a long time the least progressive part of the nation. Southern culture was rural and agricultural while the North was urbanizing and mechanizing. The “Southern aristocracy”— which in some places made up pretty much the entire literate population— nurtured delusions of European grandeur. They carefully reckoned their descent from the titled families of England and the Continent. Heredity had enormous meaning for Southerners, both for good and for ill.

The South was also the place it was hardest to pretend that evil was all somebody else’s doing. It’s ironic, really, that the Purtians’ descendants in New England (Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman) were able to forget about our fallen human nature faster than the heirs of the gentlemen adventurers who brought a more relaxed version of Protestant Christianity to Virginia. After all, original sin was a bedrock belief of the Calvinist Puritans.

But Massachusetts Puritanism also included a powerful strain of what came to be called “American exceptionalism”—Alexis de Tocqueville’s phrase for Americans’ belief that we’re special, that God has chosen America to be His in a particular way. This “exceptionalism” originated in the Puritans’ Calvinist belief that they were among the elect whom God had chosen for salvation. But the facts on the ground were probably even more significant than the different religious histories of the different regions. White Southerners knew they were implicated in what’s been called America’s original sin, the great contradiction at the heart of America’s foundation— chattel slavery, justified on the basis of race.

As slavery was outlawed in the states outside the South, the “peculiar institution” came to be the defining fact of Southern culture. Inequality and bondage were day-in, day-out realities for Southerners, who lived with slavery, and then through the war that ended it, and then in the long shadows of both. The best Southern literature is about race, in a way that no great English literature— not even Othello —really is.

Mark Twain, from Missouri, a border state, has a hybrid sensibility. He’s part cando, practical Yankee with no patience for medieval aristocratic pretensions— like the hero of his novel, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. But he’s also the native son of a slave state.

![]()

Why we should still read Huckleberry Finn (despite the ugly racial epithets)

Huckleberry Finn is a grand adventure about a journey down the great Mississippi River. It’s also a psychologically realistic portrait of a boy running away from his brutal father and a man running away from the brutal institution of slavery. The Yankee in Twain delighted to poke fun at the absurdities and hypocrisy of Southern culture, infatuated with its delusions of nobility. “The King” and “the Duke” in Huckleberry Finn, sometime Shakespearian actors and full-time con men who trade on their supposed noble blood and their victims’ cultural pretensions, are hilarious. But the Southerner in Twain could make the institution of slavery really live in his fiction.

In fact, in the character of Jim, the runaway slave, Twain reproduced some truths of a slave’s existence—the way the slave’s inferiority was taken for granted, and his real and horribly abused intimacy with the very people who denied his humanity—so vividly that Huckleberry Finn has fallen afoul of our modern censors. Jim’s ignorance is felt to be an insult to the intelligence of modern-day descendents of slaves. The words the characters in the novel use about Jim’s race seem to be violent offenses to human dignity, better not even mentioned in the classroom.

The problem that Huckleberry Finn poses to modern audiences is, in a particularly stark form, the same dilemma that all our culture sets for us. Which is the best way to handle the traces of human evil in the culture we’ve inherited from the past? “Multiculturalism” and political correctness suggest two conflicting answers.

There’s the way of multiculturalist propaganda: the crimes of the past are continually brought to our attention so that we can remind ourselves of the wickedness of our culture, and be on guard against any recurrence. This self-flagellating blame-America-first attitude is a far cry from the robust self-confidence that’s been typical of our American culture. And it inevitably leads away from American literature (whose hopelessly tainted authors can’t be trusted) to the study of social history.

There is something recognizably American in the other PC approach— the notion that if only we can cut ourselves off from the hopeless guilt of Western civilization, if only we can scrub our language clean of masculine pronouns and eradicate every last Confederate memorial from our public parks—then we’ll get beyond our hegemonic, African-enslaving, Indian-killing past into a bright new egalitarian future. From this point of view, it’s best to forget all about Huckleberry Finn.

There’s no question about what either attitude does to the study of literature—it kills it. And the death of our literary heritage might be worth it, if either perpetual self-flagellation or dropping the whole Western canon down the memory hole could ensure that no injustice on the scale of black slavery in America would ever occur again. But what if the ultimate source of that evil is not some special circumstance unique to the American South, or even to Western civilization? What if the real source of slavery and racism is in “the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself,” which are always going to be with us, no matter how we try to escape them? Then neither perpetual self-recrimination nor historical amnesia is our cure.

|

“Never again” is, by itself, never good enough—because there’s always an argument, the next time, about whether the new evil is the same thing we’ve sworn never to tolerate again. The injustice always reappears in a different form. The very parade of self-condemnation or the elaborate distancing of ourselves from the injustice of the past—by which we think we guarantee our innocence—can itself become the occasion, or even the excuse, for the next injustice.

But enforced ignorance is an even worse choice. Attempts to cut ourselves off from the knowledge of human nature that’s available in the history and literature of our culture are bound to be counter-productive. People did the appalling things that our most painful literature portrays not primarily because they were Southerners, or Americans, or colonial imperialists tarnished by the hegemonic culture of the West. They did them because they were human beings. Human culture is the record of the long struggle to understand the human condition, and human nature—which will always be with us no matter how many fresh starts we get. Knowledge of that culture is a necessary weapon ( not a liability) in the never-ending struggle for human dignity.

![]()

Literature from the Deep South

William Faulkner, the best-known Southern (and possibly the greatest American) writer, was born and bred and lived for most of his life in Mississippi: the poorest, most backward, least egalitarian state in the United States. Faulkner’s ancestors were early settlers and landowners in the Deep South; his grandfather was a colonel in the Confederate Army. Faulkner wrote a series of interconnected novels spanning more than a hundred years of fictional time, about the inhabitants of the mythical Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi.

Faulkner’s characters, like real Southerners, are defined partly by the histories of their families. The Sartorises and Compsons are shabby Mississippi gentility like Faulkner’s own family. The Snopses are sleazy white trash—early on, barn burners who resort to vandalism and animal cruelty to cover up their flight from their sharecropping debts; later on, up-and-comers who flourish in the New South economy in which the Compsons and Sartorises can’t make it.

Like the French novelist Balzac, Faulkner lets the same characters show up in different novels—in one as the hero, then in a kind of cameo appearance in another. But unlike Balzac, Faulkner uses modern narrative techniques to tell his stories. His fiction marries the experimental narrative techniques of James Joyce to the native storytelling tradition of the American South.

The Sound and the Fury and Absalom, Absalom are often said to be Faulkner’s two best novels. Parts of both books are narrated by Quentin Compson, who’s a Harvard freshman in 1909-10; he commits suicide in the spring of 1910. Absalom, Absalom is largely a story that Quentin Compson tells his Harvard roommate, a Canadian named Shrevlin McCannon. The pretensions of Southern culture are an explicit theme of the book. Quentin’s Harvard education is one of those luxuries that shabby genteel Southerners cling to, to reassure themselves that they’re really the artistocrats they believe themselves to be.

The story Quentin tells Shreve is about Thomas Sutpen and his children. The hardbitten Thomas Sutpen appears mysteriously in Jefferson, Mississippi, in 1833, acquires 100 square miles of land by tricking or coercing an Indian chief, marries the daughter of a Methodist storekeeper, and has a son, Henry, and a daughter, Judith. In 1859, Henry brings a friend, Charles Bon, home from the University of Mississippi to visit his family for Christmas. Judith falls in love with Charles. The next year Thomas Sutpen forbids Judith to marry Charles. Henry, siding with his friend, leaves home. Henry Sutpen and Charles Bon serve together in the Confederate Army for four years. In 1865, they return to Sutpen’s Hundred, Charles still intending to marry Henry’s sister. But Henry shoots and kills Charles in front of Sutpen’s house.

|

Elements of Greek tragedy, Biblical history, and Southern Gothic are freely blended in Absalom, Absalom. But at its heart the novel is a mystery—not a whodunnit, but a why-he-dunnit kind of story. Why did Henry Sutpen, who defied his own father for Charles’s sake, in the end shoot Charles rather than let him marry Henry’s sister? Quentin tells Shreve several possible versions of the story. They speculate on why Henry had to stop the marriage.

Quentin and Shreve imagine Henry, living through the War with Charles, discovering the truth about the man his sister loves. That truth has several layers. First, that Charles has a relationship—even a quasimarriage— with an “octoroon” (a woman of one eighth African descent) in New Orleans. Then, more shockingly, that Charles is Thomas Sutpen’s own first son, by a woman he married in Haiti. Quentin and Shreve imagine Henry, trying to accommodate himself to an incestuous marriage between his sister and his half-brother by telling himself stories about a French duke who married his sister and was excommunicated by the pope.

But the real answer to the mystery is none of these. Henry is determined to let Charles Bon marry Judith, even incestuously, until he meets his father in the final retreat of the Confederate Army. What his father tells him changes Henry’s mind: “ it was not until after he was born that I found out that his mother was part negro. ” It’s the miscegenation, not the incest, that Henry won’t stomach.

But Charles is determined to force his way into his father’s family, even if he dies in the attempt. As he explains to Henry, he would have abandoned his claim on Judith if at any time their father had sent him word— not even to ask him to leave her alone, but simply to acknowledge his paternity.

Thomas Sutpen is equally determined: He can’t acknowledge Charles Bon in any way. His ambition for his family depends on the color bar that’s the fundamental law of Southern culture: one drop of “negro blood” is an absolute disqualification from any kind of social status. Sutpen has to reject his own son to satisfy the craving for acceptance that’s been driving him since he was rejected as a boy—sent away from the door of the plantation house where his trashy family were sharecropping in Virginia.

Henry sees things the same way. When Bon says Henry will have to kill him to keep him from marrying Judith, Henry says he can’t, because Bon is his brother. “ No I’m not,” answers Charles, “ I’m the nigger that’s going to sleep with your sister. ” That’s why Henry shoots him.

After the murder, Sutpen tries again (and then again) for yet another fresh start. Sutpen’s final try ends in his own death, when Wash Jones, odd-job man living on the Sutpen place, kills him because he rejects Jones’s trashy granddaughter (after Sutpen lashes out in disappointment that she’s given birth to a girl, instead of the son he needs to establish a Sutpen dynasty and forever erase the image of himself as the rejected boy of his Virginia childhood).

At the end of the book, Shreve asks Quentin a final question: “Why do you hate the South?” And Quentin answers (“quickly, at once, immediately”): “I dont hate it.” But of course he does. Southern literature is great for the same reason that Southerners feel more trapped than people from other places in America. It’s awful to have to live with your mistakes, instead of moving on and forgetting them. But there’s something attractively real about Southern culture and Southern literature. What Quentin has, and feels as a burden, is a heritage that a Yankee (or a Canadian like Shreve) is naturally fascinated by—even, in some sense, envies.

Southerners have had to live with each other, in a way that a lot of other Americans haven’t even tried doing. Instead of making a fresh start, Southerners lived with their sins, and with the people they hurt and were hurt by, for generation after generation—sometimes stewing in resentment and prejudice, sometimes taking revenge—but actually living with the descendents of the people their ancestors knew: descendents of slaves lived cheek by jowl with the descendents of slavemasters. The result is, at least Southern writers are aware that fresh starts, like the one Thomas Sutpen was trying for, cost something. You can’t just erase everything you (or your ancestors) did before you decided to start again. Old sins have long shadows: in the Bible, in Greek tragedy, in Southern Gothic. Pretending you can simply move on is another rejection—of the responsibilities you carry from the past, and of the people that past binds you to—which pulls you back into the cycle of tragedy again.

![]()

“A hillbilly Thomist”

If the theme of Faulkner’s fiction is that you can never really get a fresh start, the theme of Flannery O’Connor’s is that you can—but only at an enormous price. Faulkner’s religion, insofar as he had one, was the stoicism that Walker Percy, another Southern writer, claimed was the real religion of the South. O’Connor was a Catholic—she called herself a “hillbilly Thomist”—who found in her native Bible Belt the perfect setting for stories in which God’s grace pierces through human defenses to offer self-satisfied, stiff-necked human beings one last chance to repent.

If Faulkner’s fiction is Southern Gothic, O’Connor’s is Southern grotesque. The grace O’Connor wrote about was not a comfortable thing. The New Testament passage from which she took the title of her second novel could be the motto for the whole body of her work: “From the days of John the Baptist until now, the kingdom of God suffereth violence, and the violent bear it away.” O’Connor was brought up in the narrow American Catholicism of the mid-twentieth century, but her religious education took her in an odd way. Having been taught, for example, that her guardian angel accompanied her everywhere, she used, as a child, to lock herself in a room and whirl around wildly in a circle trying to hit him. The Divine grace that O’Connor’s characters encounter is the furthest thing possible from a pious platitude; its ultimate source is something that’s more grotesque even than the events of an Edgar Allan Poe story, but that was present in one form or another in every Catholic home and every Catholic school in the 1950s: a Man nailed to a cross, dying in bitter agony.

Flannery O’Connor’s stories typically end with a gruesome act of violence. In “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” a serial murderer shoots a grandmother. In “Greenleaf” a woman is gored by a bull. In Wise Blood a man blinds himself with lime. In “The Lame Shall Enter First” a man finds the body of his son who has hanged himself; he makes this discovery at the very moment when he’s realized that he loves the boy, and that he’s been neglecting him in a vain attempt to reform a thankless juvenile delinquent. If there’s no physical violence in a story, there’s a heart-rending loss or some other horrifying revelation.

|

In “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” a young white man, Julian, is riding the bus with his mother when a black woman gets on with her little boy. Julian’s mother is mortified to discover that the black woman is wearing the very same hat she is. And Julian is mortally embarrassed by his mother’s attempts to condescend to the black family: she offers the black child a penny; the black woman responds with violent resentment. Julian is humiliated by his association with his embarrassingly out-of-date mother. She’s sacrificed for her son—“her teeth had gone unfilled so that his could be straightened”—but the education she’s given him has only turned him into a resentful small-time intellectual snob who despises her all the more because he needs her so much. He wishes he could make the black people on the bus understand where his real sympathies lie, that he, unlike his mother, has solidarity with the just aspirations of the black race. To prove the point, he makes a production of asking a black man on the bus for a light, only to realize that he doesn’t have any cigarettes. It’s only when his mother has a stroke in the midst of Julian’s self-righteous harangue that he suddenly remembers how much he needs and even really loves her.

Unhappy young intellectuals who are miserably uncomfortable in their parents’ world (some of them suspiciously like Flannery O’Connor herself) are staple characters in O’Connor’s fiction. O’Connor wrote to a friend that “Everything That Rises Must Converge” amounted to saying “a plague on everybody’s house.” In other words, she was criticizing both traditional Southern racism, in which Southern whites feel comfortably superior to blacks, and the new Southern liberalism, in which Southern liberals feel comfortably superior to their parents and their less enlightened neighbors. Both states of mind are just different versions of the tendency to locate evil somewhere else —or, as O’Connor saw it, different ways of being satisfied to live without repentance, closed off to grace.

In The Violent Bear It Away O’Connor gives us another modern liberal Southerner—a schoolteacher named Rayber who’s eager to cure his young nephew, Tarwater, of the religious fanaticism he’s been trained up in by their ancient uncle, who believed himself to be a prophet and was raising Tarwater to be a prophet, too.

The boy Tarwater has a strong revulsion to this vocation. It absolutely makes him sick to think about the Heaven the old man used to tell him about. He imagines himself sitting on a green hill stuffed full of loaves and fishes—to the point of nausea. After the old man dies, Tarwater runs away from the cabin where they lived, setting it on fire rather than bury the old man’s body. He goes to the schoolteacher uncle, hoping to find a life more to his liking in the city.

But the sociology that his schoolteacher uncle lives by isn’t strong enough to compete with the Divine grace that’s seeking a foothold in Tarwater’s life. Some of the novel’s funniest scenes show the schoolteacher’s sanitized modern worldview clashing with the old prophet’s uncompromising vision. For instance, the old man says just what he thinks (in Old Testament language) about the schoolteacher’s finding his sister a boyfriend. And the teacher writes the old man up in a magazine as a case study in self-deluded religious fanaticism, and gives him the article to read. The teacher’s up-to-date mental hygiene is really just a retreat from realities he can’t face—including his overwhelming irrational love for his retarded son. The novel ends with several appalling acts of violence, as is only to be expected in a Flannery O’Connor novel. O’Connor is bent on showing us the cost of salvation, which is the only real fresh start available to us. The further we get from understanding original sin, that most essential truth about human nature, the more violent the intervention of grace—and the literature, for that matter—has to be, to get our attention.

![]()

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Elizabeth Kantor. "American Literature: Our Own Neglected Canon." chapter eight from The Politically Incorrect Guide™ to English and American Literature (Washington D.C.: Regnery Publishing Inc., 2006): 167-185.

The Author

Elizabeth Kantor, the editor of the Conservative Book Club and a writer for Human Events. She holds her Ph.D. in English from the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and an M.A. in philosophy from Catholic University in Washington D.C. Dr. Kantor is the author of The Politically Incorrect Guide™ to English and American Literature.

Copyright © 2007 Regnery Publishing, Inc.