He heard the music of the spheres

- DOUGLAS LEBLANC

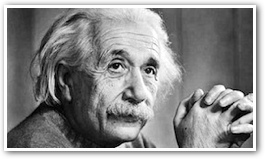

Walter Isaacson's new biography reinforces the notion of Albert Einstein as a humble scientist, especially in his relation to God and faith.

|

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) |

While interviewing Walter Isaacson on Wednesday's Fresh Air, guest host Dave Davies raised the point that Albert Einstein has become an icon of unattainable genius. True, but he's arguably the one scientist who most strongly attracted the affection of Americans. Whether because of his wonderfully untamed hair, his doleful eyes or that photo in which he sticks out his tongue, Einstein also became an icon of the scientist as approachable, and maybe even humble, human being. What other acclaimed scientist could have inspired Walter Matthau's oddball role in the film I.Q.?

Time's excerpt from Isaacson's new biography reinforce the notion of Einstein as a humble scientist, especially in his relation to God and faith.

Early on there is a glimpse of spiritual precociousness, even as the family maid called him "the dopey one":

"Consequently, when Albert turned 6 and had to go to school, his parents did not care that there was no Jewish one near their home. Instead he went to the large Catholic school in their neighborhood. As the only Jew among the 70 students in his class, he took the standard course in Catholic religion and ended up enjoying it immensely.

"Despite his parents' secularism, or perhaps because of it, Einstein rather suddenly developed a passionate zeal for Judaism. 'He was so fervent in his feelings that, on his own, he observed Jewish religious strictures in every detail,' his sister recalled. He ate no pork, kept kosher and obeyed the strictures of the Sabbath. He even composed his own hymns, which he sang to himself as he walked home from school."

Later came disenchantment:

"Through the reading of popular scientific books, I soon reached the conviction that much in the stories of the Bible could not be true. The consequence was a positively fanatic orgy of free thinking coupled with the impression that youth is intentionally being deceived by the state through lies; it was a crushing impression."

But later still came his connection with the God of Spinoza. Isaacson offers a pithy summary of an interview Einstein granted to George Sylvester Viereck, a son of Germany who eventually showed a troubling enthusiasm for Nazism:

In fact, Einstein tended to be more critical of debunkers, who seemed to lack humility or a sense of awe, than of the faithful. "The fanatical atheists," he wrote in a letter, "are like slaves who are still feeling the weight of their chains which they have thrown off after hard struggle. They are creatures who — in their grudge against traditional religion as the 'opium of the masses' — cannot hear the music of the spheres. |

"Viereck began by asking Einstein whether he considered himself a German or a Jew. 'It's possible to be both,' replied Einstein. "Nationalism is an infantile disease, the measles of mankind."

"Should Jews try to assimilate? 'We Jews have been too eager to sacrifice our idiosyncrasies in order to conform.'

"To what extent are you influenced by Christianity? 'As a child I received instruction both in the Bible and in the Talmud. I am a Jew, but I am enthralled by the luminous figure of the Nazarene.'

"You accept the historical existence of Jesus? 'Unquestionably! No one can read the Gospels without feeling the actual presence of Jesus. His personality pulsates in every word. No myth is filled with such life.'

". . . Do you believe in immortality? 'No. And one life is enough for me.'"

Most striking is Einstein's attitude toward atheists:

"'There are people who say there is no God,' he told a friend. 'But what makes me really angry is that they quote me for support of such views.' And unlike Sigmund Freud or Bertrand Russell or George Bernard Shaw, Einstein never felt the urge to denigrate those who believed in God; instead, he tended to denigrate atheists. 'What separates me from most so-called atheists is a feeling of utter humility toward the unattainable secrets of the harmony of the cosmos,' he explained.

"In fact, Einstein tended to be more critical of debunkers, who seemed to lack humility or a sense of awe, than of the faithful. 'The fanatical atheists,' he wrote in a letter, 'are like slaves who are still feeling the weight of their chains which they have thrown off after hard struggle. They are creatures who — in their grudge against traditional religion as the 'opium of the masses' — cannot hear the music of the spheres.'"

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Douglas LeBlanc. "He heard the music of the spheres." Get Religion.org (April 12, 2007).

Reprinted by permission of GetReligion.org and Douglas LeBlanc. The original posting of this article is here.

The Author

Douglas LeBlanc began covering religion in June 1984 as religion editor of the Morning Advocate in Baton Rouge, La. Since then he has worked as an editor for Compassion International, Episcopalians United (now Anglicans United), and Christianity Today. His work has appeared in Christian Research Journal, The Weekly Standard and The Wall Street Journal. Douglas is a lifelong Episcopalian but also, by choice, an evangelical Protestant. He welcomes email here.

Copyright © 2007 Get Religion