How the Church Has Changed the World: The Ordinary Man

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

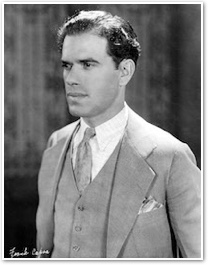

Everyone knows the name of Frank Capra from his most celebrated film, "It's a Wonderful Life".

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

Frank Capra

Frank Capra1897-1991

Here are a few things you might not know.

He came to America as a little boy with his Sicilian family, crammed in a stinking hull. When they arrived in New York Harbor, his father Salvatore pointed to the Statue of Liberty and said that its light was the greatest the world had seen since the Star of Bethlehem.

Salvatore died in a gruesome factory accident when Frank was in his teens.

Like most everybody who went into films in the twenties and thirties, Frank Capra knew what it was to be dirt poor, to be black with machine oil, to scramble from one job to another, to sing with tramps around a fire, and to bend the knee with your neighbor in worship.

He was not a pious young man. He knew divorce also; but his second wife brought him back to the faith he never quite lost.

He was first in his class at Caltech. Had he not been a director he would have been an astrophysicist.

He opposed "mass entertainment, mass production, mass education, mass everything. I was fighting," he said, for "the preservation of the liberty of the individual person against the mass." We hear echoes of the Catholic philosopher Gabriel Marcel who, in Man Against Mass Society, said that where "technique" advances, man recedes. To uphold the dignity of the human person, the Church must stand against the might of the mass phenomena, all that would reduce us to quantity or material or utility.

Let's move the camera in.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

Frank Capra was the essential American patriot, but he was not blind to how America regularly betrayed herself. He shed upon our sins the glaring light of moral analysis.

A young hayseed, Jefferson Smith (Jimmy Stewart), is appointed to a vacant seat in the Senate. He finds himself in a world that is half mad: reporters who act as hustlers and trick him into embarrassments; politicians who put partisanship above the common good and simple human decency; byzantine rules and procedures designed, it seems, to ensure that nothing gets done; and phony statesmen, including his boyhood hero (Claude Rains) bought and sold by the great money-changer in his state (Edward Arnold).

Mr. Smith would have escaped the capital without consequence, were it not for a land-deal brokered by the rich man and the senator. The deal involves a river, a Boy Scout camp, and a proposed dam. Smith's people oppose the deal, and when Smith stands against the powers, they slander him and try to ruin him; and they are formidable opponents. He is, like many a Capra hero, at the point of complete collapse, ready to give in to the darkness. He visits the Lincoln Memorial; he tries to pray to God for help; he is encouraged by a woman who first despised him as a fool, but who has come to believe in him and love him (Jean Arthur).

I was fighting," he said, for "the preservation of the liberty of the individual person against the mass."

So he uses the rules of the machine against the machine. He begins a filibuster, holding the floor indefinitely by speaking. He reads from Scripture, from the Constitution, from speeches of American statesmen. Armies of ordinary people back home have been printing broadsides of support — but the powers send out thugs to beat up the boys and destroy the papers. Scouts throng the galleries of the Senate. Mountains of letters arrive, worked up by the powers, that condemn him. He presses on, hours and long hours, till his body gives way and he falls unconscious.

I won't give away the ending. One pure, determined, innocent man against the massed forces of the inhuman: Thomas More against king and parliament, John Vianney against the dismal wake of the French Revolution, John Paul II against the Soviet machine and the cruelty of a hedonistic West.

Collective and capitalist anthills

Capra was suspicious of high-stake capitalists, like the monopolist Mr. Kirby (Edward Arnold, again) in You Can't Take It with You, and the scheming Potter (Lionel Barrymore) in It's a Wonderful Life. When he portrays them as decent men, like the self-made millionaire in It Happened One Night (Walter Connolly), they are impatient with the elites around them, and keep their working-class tastes in people and amusements.

Yet he was also a conservative Republican who detested President Roosevelt and the welfare state. How should we understand this?

At one point in It's a Wonderful Life, Mr. Potter, who owns everything in Bedford Falls but the mom-and-pop Building and Loan, insinuates that the sentimentality of its director has worked against what everybody wants, an industrious and "thrifty working class." We see the emptiness of this rhetoric when young George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart, the essential American Joe) is shown what his town would have become had he never lived. It is "Pottersville," full of strip joints, neon lights, wasted wealth, alienation, drunkenness, and misery. Some thrift.

Capra's Building and Loan towers above both anthills. It's run on a shoestring. It depends on the personal trust between the managers and the people of the working class, whose capital is not monetary but moral. It is communitarian. Each man's money helps build his neighbor's house, without passing through the sticky hands of regulators and bureaucrats. George averts the disaster of a run on the bank, covertly fomented by Potter, by reminding everyone of that trust. On the brink of the mass hysteria that Capra abhorred, they become human again; and the action they refrained from is given true expression at the end of the film, when they come together not as a mob, but as a big noisy gathering of family, friends, townsmen, and fellow worshipers in song.

The human family

The family is the seedbed of human community and real wealth. In You Can't Take It with You, the patriarch of a family of oddballs (Barrymore, playing the avuncular wise man; see his skipper in Captains Courageous), is called "Grandpa" by a whole block of renters and small businessmen, who look to him for advice. They depend on him to thwart the industrialist who wants to buy up the block and drive them off. In one scene, losing his patience, Grandpa tells the industrialist to his face that he is a failure as a man and as a father. The truth takes root in the man's soul. He is saved in the end by being reintegrated into the human race, and that means a real family, as we see him reunited with his son (Stewart, who else?), the son's fiancée (Jean Arthur), and a rout of gloriously silly human beings gathered around Grandpa's table. The industrialist was hounded by factotums and yes-men. Grandpa is surrounded by real people. His generosity allows them to join him in living "like the lilies of the field."

Yet Capra, as a friend of mine says about Charles Dickens, was in love with goodness.

Families require not prudishness but purity, and in a Capra film, purity is electric. Consider the famous "Walls of Jericho" in It Happened One Night. Clark Gable is a reporter helping a runaway socialite (Claudette Colbert) to return home. That means they have to hitchhike together, sleep in a field under some hay, ride a bus full of people singing "The Man on the Flying Trapeze," and check into a cabin at a motel. Gable slings a rope across their room and drapes blankets over it — the "walls of Jericho" — so they can undress and go to bed on either side, without compromise. Yet they are falling in love with one another.

Since it's a romantic comedy, we know that the good guy will get the girl. In the final scene, also at a motel, we don't see Colbert or Gable at all. It's the mom-and-pop proprietors, gossiping; they were afraid at first that the odd couple weren't married, but they've seen the certificate. But what did they want those blankets for? And why did the groom ask if there was a bugle anywhere (cf. Jos 6:20)?

In love with goodness

Graham Greene said that Capra's main theme was "goodness and simplicity manhandled in a deeply selfish and brutal world." Yet Capra, as a friend of mine says about Charles Dickens, was in love with goodness. Not with sweetness, niceness, political correctness, or any other saccharine substitute, but goodness, the real deal. He saw that people who follow their dreams make the world a nightmare; but people who hold true to God, their family, the place of their birth, and their neighbors — that is, the noisy people who light bonfires next door, whose kids trample your flowers to chase a ball — they are the uncalendared saints, and the means God uses to make this crazy world worth living in.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: The Ordinary Man." Magnificat (December, 2018).

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: The Ordinary Man." Magnificat (December, 2018).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2018 Magnificat