Beloved Physician and Teller of Truth

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

In the days before the telephone, people wrote letters to one another, and that included little boys sent to boarding school.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

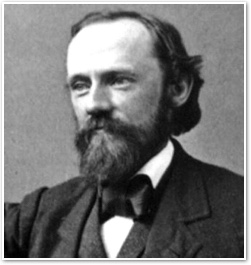

Horatio Storer, M.D.

Horatio Storer, M.D.1830-1922

One such lad named Horatio wrote his first letter home from Cape Cod, with this P.S.: "I have just come home from the seashore and as I have leisure I will add a few words. I like the school and the scholars very much. I go to the Quaker meeting. I have not been homesick in the least since I came down." Typical boy.

Horatio Storer was eight when he wrote that. He loved the seashore and its life: fish, seals, mollusks, seaweed. So after he was through with his Latin, he wandered on the beach or set out on the water. "Last Friday," he writes, at age nine, "the boys went down to Scorten Harbor and stayed all day. We made a great fire out of logs and dried beach grass, and we roasted some menhaden which we had got while the men were seining shad." His letters are filled with adventures: walking six miles to see the skeleton of a white shark, combing the woods to collect birds' eggs; hewing logs with other boys for a cabin complete with American flags and a portrait of "Tippecanoe" Harrison; and, when he was a Harvard lad, sailing all the way to Labrador.

Horatio grew up strong, immensely curious, keenly observant, and a student of God's creatures in all their wondrous forms. The Storers were Quakers, but Horatio was an explorer in faith too, as his future would show.

Horatio Storer, M.D.

Horatio's parents wanted him to be a doctor. When he was a boy he thought that studying medicine would be drudgery. But from the start Horatio was fascinated by life: what made plants and animals what they were. As a teenager he sailed to Nova Scotia with a naturalist searching for embryos of birds and fish to examine them under a microscope: they were at the beginning of embryology. They put ashore once and went to Methodist services, Horatio noting that the attendance put Boston to shame. He cared about that.

An 1850 letter to the Boston Journal shows his interest in public questions. Racialist theories were in the air. Apologists for slavery sought scientific approval. They looked for evidence that the human race was not one. So when a freak of nature — a dwarf sheep — appeared in England, and the owner then allegedly bred a flock of them, racialists claimed that something like that had happened among isolated human populations, producing different species. Young Storer would have nothing of it. He cast the whole story in doubt, seeing where the leap of reasoning tended, and insisting, as a scientist, that evidence for racialist claims was utterly lacking.

In short, Horatio Storer, M.D., was not just a genial doctor whose hands had been trained to heal. He was a scientist and man of prayer, in love with truth and the glory of God's creation. It's no surprise when we find him, at age twenty-six, taking on the case of abortion. Storer faced a moral conundrum. Doctors had been looking the other way when it came to all gynecological issues. Horatio Storer established the nation's first hospital ward for gynecology.

Embryology had progressed far enough for Storer, with his keen powers of observation and logical deduction, to show that a child in the womb is its own "nervous center, self-existing, self-acting," not inert. The leading doctors of the time agreed, and laws were reformed accordingly.

So too it was with abortion. The doctors were not sensitive so much as timid; not moral but self-protecting. But Storer would not let them evade the issue. Embryology had progressed far enough for Storer, with his keen powers of observation and logical deduction, to show that a child in the womb is its own "nervous center, self-existing, self-acting," not inert. The leading doctors of the time agreed, and laws were reformed accordingly.

Words and Deeds

His deeds paint a fuller picture. He earned a law degree at Harvard to assist lawyers in fighting the good fight; that was at his own expense. Yet he was merciful to troubled women. He admitted unwed mothers — they had nowhere else to go — to the "lying-in" hospital where he worked in Boston, to help them as best he could, and counsel them against taking wrong decisions.

Those who know they need God's grace are apt to forgive others too. At age thirty-nine, the one-time sailor boy wrote these words: "Compelled humbly to surrender to the Master my life had denied, I find a peace of which before I had had no conception, and then strangely enough, the harbor of refuge for which my ships at sea had been so long and so ineffectually struggling was reached at last on Christmas Eve." He had accepted the Trinity.

Horatio Storer, Catholic

That, however, was not the end of the voyage, for in his fifties Horatio Storer became a Roman Catholic. Imagine — a Harvard graduate, living in New England among Irish immigrants and the native English who detested them. But truth leads where it leads, and you follow it because you must. He settled in Newport, and became one of the most beloved citizens of Rhode Island. He was the last surviving member of his graduating class, retaining his sharp mind and his devout heart till his death in 1922, at age ninety-two.

He loved the Church, humbly taking instruction from her just as he had taken instruction from the men of science when he was a boy. He had to stand up for victims of racial bigotry again: French immigrants, even nuns, whom the Irish and other native Rhode Islanders didn't want around. Storer begged his friend the bishop to intervene, and he prevailed.

In his letter to the bishop we find words that would honor any Catholic in any state of life:

It is my constant prayer that if ever our Lord should permit me to do some slight thing for him, and should say to me as to Saint Thomas of Aquinas [that I had spoken well of him and might receive what I would], grace might be given me to answer, Domine, non nisi Te. Nothing, Lord, but Thee.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: "Beloved Physician and Teller of Truth." Magnificat (January, 2017).

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: "Beloved Physician and Teller of Truth." Magnificat (January, 2017).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2017 Magnificat