The Classics are not the Canon

- ROGER LUNDIN

In an age such as ours, when cynicism and suspicion can make it difficult for us to take seriously anything that fails to meet our own standards or to gratify our desires, the great classics of literature have a unique power to speak to us of our potential and our peril.

|

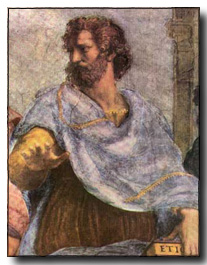

| Aristotle

detail from The School of Athens by Raphael |

In the spring of 1997, NBC broadcast a contemporary adaptation of Homer's

Odyssey. In a preview of the program, a critic for the New York Times

concluded his largely favorable review with a simple summary of the Greek

warrior's twenty-year journey that finally brings him home: Moral: There's no

place like home. Classics are not necessarily complicated.

With this tongue-in-cheek conclusion, the commentator nicely reminded his readers of an important reason why the classics have endured. They are great stories, often brought to life with vivid narratives and splendid metaphors. For all that we understandably make of them, the classics are, after all, riveting accounts of mothers and daughters, fathers and sons, and husbands and wives; they tell of the heights of human aspiration for God and the good and of the depths of human misery and depravity. Man is broad, says a character in Fyodor Dostoyevsky's classic novel, The Brothers Karamazov. Here the devil is struggling with God, and the battlefield is the human heart. Although there is endless complexity in the classics and in their influence over culture, they are not necessarily complicated because they deal in the most fundamental human realities in God's world.

A CANON FOR THE CANONLESS

In spite of their enduring power and widespread appeal, in recent years the classics have been the subject of much controversy. They have been accused of everything from the creation of oppressive patriarchy to the instigation of racist actions and genocidal impulses. Some see the classics as trivial; others view them as hopelessly exclusive; still others question the very idea of distinguishing between supposedly classic works and all other forms of human creation.

In many instances, these disputes about the nature and worth of the classics are needlessly confused by a failure to distinguish between the question of the classic and the question of the canon. As the contemporary literary scholar Joel Weinsheimer points out, we have come to treat the classic and the canon as though these two very different things were the same. It is a mistake to do so, because although the canonical and the classical have a number of things in common, the differences between them are real and essential to understanding the classics properly.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term canon means any collection or list of sacred works accepted as genuine. The term, of course, has its roots in the history of the Christian church, for it named the body of diverse works that came to make up the Old and New Testaments of the Christian Scriptures. For almost two thousand years, whether in Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, or the many branches of Protestantism, the scriptural canon was a closed body of books considered to be inspired by God, revelatory, and authoritative.

Only in the nineteenth century did the idea of a canon of literary works emerge in a way to supplant the ancient biblical model. Especially in the second half of that century, there arose a body of criticism that argued in favor of the idea of poetry, drama, and fiction serving as a form of secular scripture a canon for the canonless in a post-Christian world. In a time when orthodox faith and practice seemed to be losing their authoritative hold over the minds of many people, some thought that a literary canon might replace the discredited biblical canon.

The Victorian poet and man of letters Matthew Arnold was a pivotal figure in the move for literary works to assume such canonical status. In his famous formulation, we in the modern world must be about the business of acquainting ourselves with the best that has been thought and said in the world.

For almost a century, Arnold's ideal held sway over the study of literature in the English speaking world, as scholars and publishers promoted the idea of a fixed canon of great books. In the last decades of the twentieth century, however, that idea was subjected to a withering critique. Under the influence of what has been called the hermeneutics of suspicion, postmodern theories of interpretation questioned the claims made on behalf of the canon to truth and universal value. Because the canon largely contained works written by white males in the Western tradition, it was frequently portrayed as an instrument of oppression and exclusion. Rather than revealing truth and universal values, it was held, the canon concealed the relations by means of which men controlled women, the white race dominated people of color, and the industrialized West exploited the third world.

Both the attackers and defenders of the canon have often confused the question of the classic and the canon. Postmodern critics have been prone to see all works of literature as texts to be decoded for their concealed messages of power, while traditionalists have too often reacted as though any criticism of the traditional canon was an assault upon the very foundations of truth, rationality, and virtue. To a certain extent the confusion of both sides is understandable, for some of the works in the literary canon celebrated by Arnold and his cultural descendants were ones that we would call classics. They included the epics of Homer and Greek tragedy, Virgil's Aeneid and the Latin poets, as well as such undisputed monuments of English literature as Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, Milton's Paradise Lost, and certain of Shakespeare's plays. But the canon as the modern literary establishment defined it also included works that we no longer think of as classics, because their lasting significance has come into question.

PASSING FASHIONS, ENDURING FOUNDATIONS

The interesting fact has been noted that as a noun canon is a collective term for a group of works but that no word exists in English to designate a single canonical poem, play, or novel. At the same time, classic as a noun applied only to individual works, and we have no word for the collective group of works made up by individual classics. From this curious verbal fact, a literary critic draws the conclusion that a canon is plural but determinate; that is, literary canons include a number of works but are inherently exclusionary. The classic, by contrast, is essentially singular, but the number of classics is potentially unlimited. By its very nature, the classic is a more inclusive and flexible concept than the canon.

In the canon, any number of works go in and out of fashion with each passing generation, while classics endure from age to age. Because it is so readily affected by shifts in judgment, taste, and values, the canon constantly undergoes realignment. Over the last several decades, for instance, a heightened sensitivity to historical exclusion and injustice has served to bring a number of hitherto neglected works by women and minorities into the canon. To make room for these new additions, other works once considered canonical lose their standing and are dropped from the canon. The poetry of a number of mid-nineteenth-century New England men, for example, has all but disappeared from the anthologies that catalogue the canon. Longfellow, Lowell, and Whittier are out, and Phyllis Wheatly, Frederick Douglass, and Toni Morrison are in.

The case is very different with the classic. It is inconceivable that at any time in the future Homer's Odyssey, Dante's Divine Comedy, or the tragedies of Shakespeare will fall completely out of favor and no longer be read, taught, or imitated. They are too much a part of history ever to be removed. The role of the classics in the formation of modern culture is so foundational that in a very real sense, we know the classics before we read them. Their values, visions, stories, and metaphors have shaped our culture and our self-understanding in myriad ways that are undeniable but impossible to quantify.

As a case in point, we might consider the example of one of the key classical genres, the epic. Homer's Iliad and Odyssey and Virgil's Aeneid stand unarguably as the greatest of the classical epic narratives in the Western tradition. And though written in pagan cultures, these works have had an incalculable influence on the history of the Christian church and Christian culture. In the first centuries of the Christian era, Homer and Virgil shaped Christian reflection in complex ways, and in later centuries, they directly influenced some of the greatest enduring works of Christian culture. Dante's Divine Comedy, Milton's Paradise Lost, and Wordsworth's The Prelude, to name but a few, are unimaginable without the guiding influence of Homer and Virgil. At the heart of the classic's enduring power is its irreplaceable role in shaping the history of culture.

If the classic were only important as a general influence on culture, it might be of little more than academic concern. What makes the classic vitally alive is its power to speak directly to us across the span of centuries. Because it comes down to us from a distant time and unfamiliar culture, the classic always has some quality of strangeness; yet because it has shaped so significantly the culture we inhabit, it also has a ring of the familiar. The German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer argues that the classic speaks in such a way that it is not a statement about what is past . . . rather, it says something to the present as if it were said specifically to it.

QUESTIONS FOR EACH OF US

One of the classic's greatest powers is its ability to question us and our most cherished values to talk back to us when we interrogate. The nineteenth-century German philosopher G. W F Hegel spoke of the classic as a question, an address to the responsive breast, a call to the mind and the spirit. Like the Scriptures, the classic makes a claim upon us to which we must respond. It challenges our understanding of God, our values, and our very sense of ourselves.

The Bible, especially the Old Testament, contains many accounts of God's questioning of humanity. In fact, the very first time God speaks to Adam and Even after the fall, he addresses them with questions: Where are you? Have you eaten from the tree of which I commanded you not to eat? What is this that you have done? By means of questions, God calls us to account and makes us responsible for the thoughts of our minds, the deeds of our hands, and the inclinations of our hearts.

In a similar way, when we read a classic we are not simply critics who ask questions of the text; we are also the subject of the work's own scrutiny as it requires us to review our deepest beliefs. The Christian student of culture would never wish to confuse the power of the classic with the authority of the Scriptures. The Bible is the Word of God while the greatest classics are only supreme embodiments of human insight. Nevertheless, there is something like a divine weight to the questions that the classics ask of our lives. The writer of the letter to the Hebrews in the New Testament says that the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing until it divides soul from spirit, joints from marrow; it is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart (NRSV).

In an age such as ours, when cynicism and suspicion can make it difficult for us to take seriously anything that fails to meet our own standards or to gratify our desires, the great classics of literature have a unique power to speak to us of our potential and our peril. For that, we should be ever grateful.

|

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Lundin, Roger. The 'Classics' Are Not the 'Canon'. In Invitation to the Classics (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House Company, 1998), 25-33.

Reprinted by permission of the publisher. Order Invitation to the Classics by clicking on the picture of the book at the right.

The Author

Roger Lundin is professor of English at Wheaton College. He is the author of The Culture of Interpretation and a biography of Emily Dickinson in The Library of Religious Biography series.

Copyright © 1998 Baker Book House Company