Flannery OConnor on the Banning of Books in High Schools

- ANDREW ELLISON

One of my favorite short essays by Flannery OConnor is a piece called Total Effect and the Eighth Grade, found in the posthumous collection entitled Mystery and Manners.

|

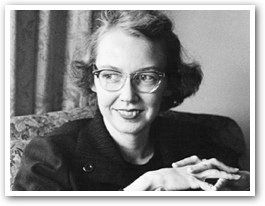

Flannery O'Connor

1925-1964 |

In this little four-page piece, O'Connor offers a Catholic artist's perspective on a familiar problem: schools assigning "offensive" books to students. (Her own works were once infamously banned in schools – by a Catholic bishop in Louisiana in 2000.)

Writing in 1963, she sets the scene as follows:

In two recent instances in Georgia, parents have objected to their eighth and ninth grade children's reading assignments in modern fiction. This seems to happen with some regularity in cases throughout the country. The unwitting parent picks up his child's book, glances through it, comes upon passages of erotic detail or profanity and takes off at once to complain to the school board.

This issue always seems to bring out intense sentiment on both sides. Clear and rational thought, never in abundant supply amongst us sinners, is easily choked out by the passions triggered by arguments about banning books. We see parents outraged by supposed assaults upon their children's purity, undertaken by the very adults they had trusted to keep their children intellectually and morally safe; on the other side we find reflexive cries of "Censorship! Puritanism!" and the hysteria of the school librarian-type who genuinely believes she is the only one left to protect civilization from the vandals, fanatics, and book-burners who would destroy what they haven't even tried to read, probably because they can't.

O'Connor's analysis of the problem avoids both of these well-worn ruts in the road. Her analysis is crisp and refreshing, and her proposed solution should be a model for ALL schools, or at least for Catholic schools.

The real problem, she says, is not that the schools are assigning "dirty" books, but that they are assigning apreponderanceof modern books, and that there seems to be no clear purpose behind the teaching of literature in most middle and high schools other than to try to capture the "interest" of the adolescent mind. This principle – the idea that it is the school's duty to excite or gratify the unformed tastes of teenagers – she calls "the devil of Educationismthe kind that can be cast out only by prayer and fasting," and she notes with bemusement that mid-20th century America seems to be "the first age in history which has asked the child what he would tolerate learning."

And modern fiction is certainly well-equipped to seize the interest of the teenager: instead of long, difficult sentences with lots of subordinate clauses, unfamiliar vocabulary like "ope" and "cognizance", and the inscrutably strange customs of the Regency-era English country aristocracy, modern fiction gives us men and women engaged in the blunt and often brutal business of modern life. Loving, fighting, spending, stealing. In short sentences. Much easier.

And modern literature, even when it is first-class art, is so much more likely to be, well, dirty than the great prose and poetry of the past 500 years, which is another reason why it has the power to seize the interest of the unformed young reader:

The (modern) author has for the most part absented himselffrom direct participation in the work and has left the reader to make his own way amid experienceThe modern novelist merges the reader in the experience; he tends to raise the passions he touches upon.

It is here that the moral problem will arise. It is one thing for a child to read about adultery in the Bible or Anna Karenina and quite another for him to read about it in most modern fictionmodern writing involves the reader in the action with a new degree of intensity, and literary mores now permit him to be involved in any action a human being can perform.

"And if the student finds that this is not to his taste? Well, that is regrettable. His taste should not be consulted; it is being formed." |

Great literature has always portrayed characters fornicating and killing. What has changed is that the way the modern writer portrays such acts in literature, even a devout Catholic modern with an intense moral sense like O'Connor (she would insist: ESPECIALLY a devout Catholic modern with an intense moral sense), is graphic, explicit, a kind of total immersion in dirty deeds. Such modern writing is strong stuff; it is not to everyone's liking, and sometimes it can be a little TOO much to the liking of the 15-year old mind, and for the wrong reasons. But this kind of literary technique is not ipso facto "immoral" writing, and it may be very suitable for the reader who has the moral and the literary experience to understand and appreciate it.

But it is highly unlikely that the high school student has this moral and literary experience; the schools aren't even trying to impart just the aesthetic education that could enable the proper understanding of 20th century fiction; they are just assigning such modern fiction to their students with no context, which is really just as preposterous as dropping calculus on a 6th grader, or taking a group of kids who have never heard anything by Bach or Mozart to hear some atonal, avant-garde recital.

To make modern/contemporary literature the predominant or sole business of the high school English class is to commit the serious error of putting second things first; it is to deny students sight of the literary works of the past which are the only things that can help them to intelligently judge the works of the present. Here O'Connor is concrete in her recommendations, declaring that Steinbeck should be off limits to students who haven't read, under a teacher's intelligent guidance, earlier American writers like Nathaniel Hawthorne or James Fenimore Cooper, but that even these books should be set aside until even earlier English novelists' works have been read and understood.

(She doesn't go back further, but one could easily take her recommendations further: why not start with the Bible, Homer, and Vergil, and then work one's way up through Dante, Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Milton?)

The proper business of the high school, O'Connor asserts, is "preparing foundations"; it is ABSOLUTELY NOT immersing young people in the already-too-familiar aesthetic tastes and moral realities of modernity; it is certainly not amusing them with exciting stories of sex and violence.

And if the student finds that this is not to his taste? Well, that is regrettable. His taste should not be consulted; it is being formed.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Andrew Ellison. "Flannery OConnor on the Banning of Books in High Schools." Catholic Phoenix (February 24, 2011).

Catholic Phoenix is an internet site published by Catholic contributors who live in Phoenix, Arizona.

- The Formal Cause of Catholic Phoenix discusses the structure of the site and the wide variety you'll find here.

- The Material Cause of Catholic Phoenix tells you about where the posts come from and who produces them.

- The Efficient Cause of Catholic Phoenix explains how the site comes together and how it's intended to operate.

- The Final Cause of Catholic Phoenix outlines the goals of the site and why we bother to maintain it in existence.

And if you're puzzled by this talk about four causes, either read this explanation or just relax and enjoy the site.

The Author

Andrew Ellison, headmaster of Veritas Preparatory Academy, a public liberal arts charter school (www.greatheartsaz.org). A convert to the Catholic faith, Ellison lives in Phoenix with his wife Laura and their five children.