Imagination: The Hearts Best Guide

- WILLIAM KILPATRICK, GREGORY WOLFE, AND SUZANNE M. WOLFE

Concepts such as virtue, good example, and character have been out of fashion in our society for quite some time, and their absence is reflected in the available guidebooks to childrens literature. What is missing from these guides what seems to be avoided is any suggestion that certain books may help to develop character, and that others may not. The distinctive feature of this book, by contrast, is its focus on the moral dimension of reading.

|

WHEN HER TWO-YEAR-OLD sister began to cry over a missing stuffed bear, Crystal, age four, declared, "She wants her Dogger" and proceeded to offer one of her own stuffed animals as a substitute. Dogger is a story about a boy who loses his worn, stuffed dog, and about his older sister, Bella, who trades a large and beautiful stuffed bear to get Dogger back for him. Crystal, who had heard the story only the night before, was putting into practice the good example set by Bella.

Crystal is a lucky girl. Her mother reads to her. And her mother is selective in what she reads. As a result, Crystal is beginning to develop a picture in her mind of the way things should be, of how people can act when they're at their best.

This book is intended to introduce the reader to books that help youngsters grow in virtue books like Dogger. There is no shortage of such books. In fact, there are thousands of finely crafted stories for children that make honesty, responsibility, and compassion come alive. But they are not always easy to find. Concepts such as virtue, good example, and character have been out of fashion in our society for quite some time, and their absence is reflected in the available guidebooks to children's literature. Although there are many such guides, they all suffer from a common limitation: that is, their focus is almost solely on readability or, worse, on popularity. What is missing from these guides what seems to be avoided is any suggestion that certain books may help to develop character, and that others may not. The distinctive feature of this book, by contrast, is its focus on the moral dimension of reading. We think many parents want books for their children that are not simply a good read but good in the other sense of the word books that not only capture the imagination, but cultivate the conscience as well.

Such books bestow a double blessing. They provide hours of pure pleasure. They also provide good companions. They introduce your child to friends who are a little older, a little wiser, a little braver. Along with these companions your child gets to ask some tough questions. Is Long John Silver good or bad? Should Beauty keep her promise to Beast? Should Frodo continue on his seemingly doomed mission while there is still chance to return to the safety of the Shire? These are not easy questions to answer, especially when time is running out or the edge of the cliff is crumbling underfoot, but they are the kind of questions with which we are all confronted sooner or later. And when they come they often come in situations in which we, have little time to think or at times when we may be angry, fearful, or just plain exhausted. It's exactly at times like this that the half-forgotten memory of a story can rise to our aid.

A 1985 report by the National Commission on Reading declared that reading aloud is the single most important contribution that parents can make toward their child's success in school. We want to go a little further than that. We believe that, reading aloud may also be one of the most important contributions parents can make toward developing good character in their children. Why? For several reasons. First, because stories can create an emotional attachment to goodness, a desire to do the right thing. Second, because stories provide a wealth of good examples the kind of examples that are often missing from a child's day-to-day environment. Third, because stories familiarize youngsters with the codes of conduct they need to know. Finally, because stories help to make sense out of life, help us to cast our own lives as stories. And unless this sense of meaning is acquired at an early age and reinforced as we grow older, there simply is no moral growth.

Why is a book of this nature so crucial now? After all, the importance of reading has long been known. We know that millions of Americans, young and old, are crippled in their daily activities and in their future prospects by poor reading skills. The problems caused by illiteracy are all too evident. But there is a new factor to contend with. We are now faced with another kind of illiteracy one that may prove even more costly to our society. The new illiteracy is moral illiteracy. In addition to the millions who can't read or can't read well, there are millions more who don't know the difference between right and wrong or don't care.

Across the country, teachers, parents, and police are encountering more and more youngsters who don't really think that stealing or lying or cheating is wrong. Says a fifth-grade teacher quoted in Thomas Lickona's Educating for Character:

About ten years ago I showed my class some moral dilemma film strips. I found they knew right from wrong, even if they didn't always practice it. Now I find more and more of them don't know. They don't think it's wrong to pick up another person's property without their permission or to go into somebody else's desk. They barge between two adults when they're talking and seem to lack manners in general. You want to ask them, "Didn't your mother ever teach you that?"

There is an important sense in which the two kinds of illiteracy as well as the solutions to them are connected. One way to help youngsters to know and care about right and wrong is to acquaint them with good books. When we see others from the inside, as we do in stories, when we live with them, and hurt with them, and hope with them, we learn a new respect for people. This was understood by our ancestors. Stories, histories, and myths played an essential role in character education in the past. The Greeks learned about right and wrong from the example of Ulysses and Penelope, and a host of other characters. The Romans learned about virtue and vice from Plutarch's Lives. Jews and Christians learned from Bible stories or stories about the lives of prophets, saints, missionaries, martyrs. And new research suggests that they were right. In the June 1990 issue of American Psychologist, Paul Vitz, a professor at New York University, provides an extensive survey of recent psychological studies, all pointing to "the central importance of stories in developing the moral life." Narrative plots have a powerful influence on us, says Vitz, because we tend to interpret our own lives as stories or narratives. "Indeed ' " he writes, "it is almost impossible not to think this way."

But why stories?. Why not simply explain the difference between right and wrong to your children? Why not supply them with a list of dos and don'ts?

Such explanations are important, of course, but they fail to touch children on the level where it really matters the level of imagination. Imagination. The word comes from "image" a mental picture. And these pictures have a way of sticking in our memory and making demands on our conscience long after the explanations have been rubbed thin by the frictions of daily life.

There is just such an image in Lois Lowry's book Number the Stars, a story about the Nazi occupation of Denmark. To protect her Jewish friend, a Christian girl tears from her neck a gold chain bearing a Star of David and clenches it in her fist moments before Nazi soldiers arrive. She clenches it so tightly that, by the time the soldiers have left, an impression of the Star of David is imprinted in her palm.

A fourth-grade teacher who had read the book to her class passed on the following story to Lowry. On the day the teacher read that particular chapter, she had brought into the class a chain and a Star of David similar to the one described in the book. As she read the chapter she had the students pass the chain around the class. And while she was reading she noticed that one student after another pressed the star into his or her palm, making an imprint.

And that's the kind of imprint a good story can make on our minds. We need moral propositions and moral principles, but we need images too, because we think more readily in pictures than in propositions. And when a moral principle has the power to move us to action, it is often because it is backed up by a picture or image. As the short story writer Flannery O'Connor observed, "A story is a way to say something that can't be said any other way... You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate."

Stories present us not only with memorable pictures, but with dramas. Through the power of the imagination we become vicarious participants in the story, sharing the hero's or heroine's choices and challenges. We literally "identify" ourselves with our favorite characters, and thus their actions become our actions. In a story we meet characters who have something to learn; otherwise we would not be interested in them. When we first meet the hero, he has not achieved moral perfection or ultimate wisdom. If the story grips us, though, we root for the hero, suffering with him and cheering him on. This imaginative process of participation and identification gives us hope, because we want to believe that in the stories of our lives we too can make the right choices.

Are stories alone sufficient for the task of raising good children? No, of course not. Parents also need to set a good personal example, to encourage good habits, to explain rules, and to enforce them through appropriate discipline. There is no single "magic bullet" approach when it comes to raising children. But we do feel that a reemphasis on storytelling is long past due because, if anything, the power of stories has been vastly underrated in recent decades. The world of books and stories constitutes an enormous but neglected moral resource a huge treasure house lying largely unused. According to one study, once out of school, nearly 60 percent of adult Americans never read a single book. And even in school there is likely to be a reading gap. Jim Trelease says he was prompted to write The Read-Aloud Handbook when he discovered that in many classrooms he visited, the only books children were familiar with were their textbooks.

Why this neglect of books? Part of the reason, again, is that we seem to have forgotten about the power of imagination. We've forgotten that children are motivated far more by what attracts the imagination than by what appeals to reason. We've forgotten that their behavior is shaped to a large extent by the dramas that play in the theaters of their minds.

. The other reason for the neglect is television. "Television," as one critic says, "eats books." Because we've underestimated the power of imagination, that power has slipped more and more into the hands of people whose main interest in children is a commercial one. More and more, the songs, stories, and images that play in the minds of young people are the ones that are put there by the entertainment industry. If you have any doubts about the power of images, take a few minutes to observe the mesmerizing effect that TV and MTV have on youngsters. Better yet, look into the latest research on television and film violence. There is a growing consensus that repeated exposure to violent or sexual scenes does have a profound effect on the attitudes and behavior of young people.

Moreover, television as a medium does little or nothing to extend the imagination. Instead of drawing us inside the story, in the manner of a book, television forces us to remain spectators, outside the action. Increasingly, television serves up meaningless conflicts that are, more often than not, resolved by violence. Precisely because we are outside the action, scenes of violence can't hurt us; they can only provide us with a diminishing number of emotional jolts. The same syndrome affects the depiction of romantic love and sexuality. In the absence of real, believable relationships on the screen, sex becomes the only means by which characters come together.

If you as a parent don't take steps to educate your child's imagination, it's an almost sure bet that his imagination will be seduced by the power of popular culture. You need a way to inoculate his imagination against the electronic viruses he will be exposed to as he grows older. Books are one of the best ways to do this, because they provide a ground for judgment and comparison. They help us develop a "sense" that alerts us when something is morally out of tune.

A mother we know recalls a discussion with her thirteen-year-old son about a popular rock star whose songs encouraged sexual experimentation and rebelliousness. "He's just like the Pied Piper, isn't he, Mom?" remarked the boy. That's the kind of perceptive observation that reading makes possible, and it's an insight that's not likely to occur to a youngster whose only exposure has been to television.

Beyond sharpening perceptions, books enter and occupy and make safer those areas of heart and mind targeted by popular culture. In Honey for a Child's Heart, a guide to children's classics, Gladys Hunt writes, "A good book has a profound kind of morality not a cheap, sentimental sort which thrives on shallow plots and superficial heroes, but the sort of force which inspires the reader's inner life and draws out all that is noble ... I cannot believe that children exposed to the best of literature will later choose that which is cheap and demeaning."

Hunt may be overstating the case slightly individuals are always free to turn away from what is noble but she is right in her belief that good literature increases our resistance to cheapening influences. Children who read have broader sympathies and a larger picture of life. They develop more powerful, healthy, and discerning imaginations.

And imagination is one of the keys to virtue. It's not enough to know what's right. It's also necessary to desire to do right. Desire, in turn, is directed to a large extent by imagination. In theory, reason should guide our moral choices, but in practice it is imagination much more than reason that calls the shots. Too often our reason obediently submits to what our imagination has already decided. This was well understood by Plato, who had quite a bit to say about educating the imagination. Children, he said, should be brought up in such a way that they will fall in love with virtue and hate vice. How does a child fall in love with virtue? By being exposed to the right kind of stories, music, and art, said Plato. Such an education helps a child develop the right sort of likes and dislikes, and without those dispositions it won't matter how much formal training in ethics a youngster later receives.

This is why books are so important for moral education. They inspire a love of goodness. Who can read about King Midas and his golden touch without desiring to always put people before possessions? Who can read A Christmas Carol without desiring like Scrooge to honor Christmas in his heart and keep it there all year? Who can read To Kill a Mockingbird without wishing to be a little more like Atticus Finch a little braver, kinder, wiser. And who can resist the attractions of Sir Percy Blakeney, the Scarlet Pimpernel, as he carries off his bold exploits with coolness, wit, and charm? After reading The Scarlet Pimpernel, one young teenager of our acquaintance was so caught up by its exuberant spirit that he went about the house for the next week reciting Sir Percy's catchy poem about the Pimpernel:

We seek him here, we seek him there Those Frenchies seek him everywhere. Is he in heaven? Is he in hell? That damned, elusive Pimpernel.

Stories, then, because of their hold on the imagination, can help to create an emotional attachment to goodness. If other things are in place, that emotional attraction can then grow into a real commitment to goodness. The dramatic nature of stories enables us to "rehearse" moral decisions, strengthening our solidarity with the good. But if the desire to do right is not developed at an early age our other efforts to teach values to children won't bear much fruit.

What prevents parents from taking steps in this direction? Curiously, one of the biggest obstacles is a sense of fate. Curious, because we were long ago supposed to have emerged from a belief in fate. Nevertheless, it's there. Instead of doing something to break the media's stranglehold on our children, we take an attitude similar to that of primitive people who, in the face of famine or plague or flood, could only throw up their hands and say "The gods are angry" or some such formula. It's the same with us. Too many adults, when they see the pervasive influence of popular culture, tend to throw up their hands and say "What can you do?" Like the parents in the old story, we watch helplessly as today's pied pipers lead our children off in all the wrong directions. Although we live in a modern age we have succumbed to an old myth: the myth of the powerless individual against an all-powerful force.

Not that thinking mythically is a bad thing. Perhaps if we kept in better touch with the myths and stories of our civilization we wouldn't give up so easily. Perhaps we need to refresh our imaginations with stories of individuals who overcame the odds: David defeating Goliath, Horatius holding the Tiber bridge against the foes of Rome, or, perhaps most appropriately for our television-dominated age, Odysseus outwitting Cyclops, the original one-eyed giant.

"How shall a man judge what to do in such times?" asks a character in The Lord of the Rings. "As he ever has judged,' comes the reply. "Good and evil have not changed .... It is man's part to discern them." The more we expose our children to good literature the more they will develop such habits of discernment. Gladys Hunt recounts the following from a phone conversation with her college-age son:

Am I ever glad we read That Hideous Strength together last summer! I found myself in a situation this week in which I felt all the pressures to conform to the group and compromise my values to be part of the inner-ring. Then I remembered that story and the awful mistake it is to play the game that way.

That passage says a lot about literature's power to put the imagination on alert, but there's something else of interest that may have caught your attention. Reading together? A college student? With his family? It seems hard to believe. Hasn't TV made that sort of scenario impossible? Don't we have to resign ourselves to the fact that once adolescence is reached (or sooner) youngsters will retreat into a world of headphones and Nintendo? And won't that be the end of any shared world of ideas?

Not necessarily. In the days before television, reading aloud from Dickens, from Walter Scott, from treasured poets was common fare for families. It was also common for favorite books to be passed around among adults and older children. There are many families today who carry on the same practices. And, if anything, their number may now be on the increase, thanks in part to the influence of books like Jim Trelease's The Read-Aloud Handbook. Mr. Trelease is not one who thinks reading aloud is only for children. It's great for adolescents and adults, too, says Trelease:

Secondary students being read to? Certainly... When my daughter returned from England after a summer studying at Cambridge University, she told me the professors read aloud to literature classes all the time. A year later, I met a Kansas teacher returning from her second straight summer at Oxford University, where she'd been read to regularly. I figure that if it's good enough for Oxford and Cambridge, it's good enough for any junior or senior high school in America.

Why does shared reading work? It works because the right book, read in the right way, brings a thrill of excitement and enchantment. No one who has traveled with Frodo through the land of Mordor in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings is likely to complain that the journey is a long one. No one who has stood on the deck of the Dawn Treader in the company of Caspian and Reepicheep is likely to regret the experience of listening to C. S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia. No child who has trembled in fear with Beauty in the castle of the Beast is ever likely to forget that strange story of love's transforming power.

But how about the adult reader? Isn't reading aloud to children, especially very young children, a bit of a bore? Something done out of a sense of duty? Not at all. Indeed, the adult reader, who can understand all the levels of a story, may have the most fun of all. As Gladys Hunt writes, "They [children] may read the story again years later and find that their experiences in life help them see more. Adults will read the same book and begin to better understand why they loved it as children." Reread some of the better children's books and you may be surprised to discover how adult (in the best sense of the word) they are. You will find it difficult to adopt a condescending attitude toward them. For one thing, the "lesson" may apply as much to you as it does to your child; for another, the writing is often of exceptional quality. Both C. S. Lewis and Isaac Bashevis Singer observed that children are deeply concerned with serious questions, more so than adults may realize; and both men said that they couldn't imagine writing something for children that they themselves would not want to read. "I am almost inclined to set it up as a canon , wrote Lewis, "that a children's story which is only enjoyed by children is a bad children's story." Lewis was of the opinion that no book is worth reading at age ten that is not equally worth reading at age fifty.

If you're a parent, you've got a battle on your hands a battle with popular culture over your child's imagination. And like every battle this one has moments when it seems impossible to carry on. But it's not all grim, because one of the best ways of empowering your child's imagination is also one of the most enjoyable. The books we've listed are stories of virtue and character, but they are many other things as well. Some of them are hilarious, some mysterious, some adventurous, some heartbreakingly poignant, some a combination of all of these.

You will enjoy sharing them with your children. And you will find an added benefit. just as good stories help to create an emotional bond to goodness, family reading strengthens the family bond. Shared reading draws families together. It provides mutual delight and builds emotional bridges. It establishes intimacy between parent and child in a way that few other activities can match. And this is true whether you read aloud to a younger child, pass along a favorite story to an older reader, or pick up a book a child has recommended to you. If we feel an obligation to get to know our children's friends, then we should also enter their imaginative worlds with enthusiasm and respect.

But how, exactly, do stories do their work? How do they stimulate the moral imagination? How do they catch us up in their net and make us feel a part of some larger enterprise? And how do they do all this without falling into the pit of preachiness?

Read on!

![]()

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Kilpatrick, William, & Gregory and Suzanne M. Wolfe. "Imagination: The Heart's Best Guide." Chapter 1 in Books That Build Character: A Guide to Teaching Your Child Moral Values Through Stories (New York, Touchstone, 1994), 17-27.

Reprinted by permission of William Kilpatrick, Gregory Wolfe, and Suzanne M. Wolfe.

The Author

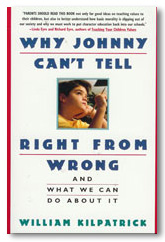

William K. Kilpatrick is Professor Emeritus of Education at Boston College and the author of: Christianity, Islam, and Atheism: The Struggle for the Soul of the West, Great Lessons in Virtue and Character: A Treasury of Classic Animal Stories, Books that Build Character: A Guide to Teaching your Child Moral Values Through Stories and Why Johnny Can't Tell Right from Wrong. William Kilpatrick is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

William K. Kilpatrick is Professor Emeritus of Education at Boston College and the author of: Christianity, Islam, and Atheism: The Struggle for the Soul of the West, Great Lessons in Virtue and Character: A Treasury of Classic Animal Stories, Books that Build Character: A Guide to Teaching your Child Moral Values Through Stories and Why Johnny Can't Tell Right from Wrong. William Kilpatrick is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Gregory and Suzanne M. Wolfe created The Golden Key, an award-winning children's book catalogue, Climb High, Climb Far : Inspiration for Life's Challenges from the World's Great Moral Traditions and Circle of Grace: Praying with and for Your Children

Copyright © 1994 William Kilpatrick, Gregory Wolfe, and Suzanne M. Wolfe