The Unquiet Men

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

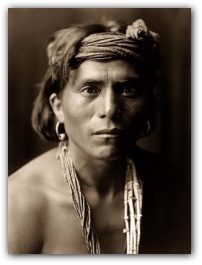

On those who are leaving the reservation.

|

"You speak to the white man," says the Indian chief, his countenance scarred with age and battle. "You tell them, Big McLintock."

The broad-shouldered rancher (John Wayne) and the Apaches are standing in front of a covered stage, where the dignitaries of the territory are meeting to round up these last Indian braves and take them to the reservation that the federal government has kindly provided for them. The Apaches are beaten, and know it. The world they loved is gone forever. There will be no war-joy, and no roaming freely across the plains with their women and children, in pursuit of the deer and the buffalo.

That taming of the Indian may be necessary for the growth of the United States, as the director of McLintock (Andrew McLaglen, under the inspiration of the great John Ford), seems to concede, grudgingly. But it may come at a terrible price, not to the Indian, but to the nation.

To Remain Men

"Tell the chief," says the territorial governor to McLintock, "that there will be food on the reservation, and schools, and medicine. Tell them that they will be cared for."

We may take the governor at his word, in this late and not wholly successful western. The Indians will be cared for, more or less. But Puma, the chief, cannot accept that promise. It is not that he believes the white man is lying. If only he were lying, Puma would have some hope! Instead, he explains to McLintock that he cannot accept life on those terms.

Long ago he had come within an inch of ending McLintock's life -- they were old enemies, back when McLintock was fighting to maintain his scrap of ranch land against man and the elements. That is why Puma has come to McLintock now to plead his case. They have a friendship or a mutual respect built upon those days of gun and arrow and fire and sword.

"Chief Puma," says McLintock, "says that the life you promise his people may be fit for women, but it is not a life for Apache braves. If a man must be provided with his own food, then he is no longer a man. All the Apache ask for is the freedom to hunt as they used to do."

Puma wants no more than that. It is already a sad compromise. The women and children will live on the reservation. The men will live there also, when they are not hunting. Raids on forts and settlements will cease. All the men are asking for, says McLintock to the citified, "civilized" half-men on the stage, is the permission to remain men.

Permission denied. The casual moviegoer will suppose that it is but another criticism of the foolish and miserable treatment of the Indians by their white conquerors. But it is far more than that. Director McLaglen is echoing the master here, and he, John Ford, had always cast a discerning eye upon the deadening blandness of a certain kind of civilization we take for granted. At the end of Stagecoach, when the young John Wayne walks away with his lady Dallas, the one-time saloon girl, it is to hard but real life on a ranch far beyond the reach of the local Temperance League. Says his friend the boozy doctor, with a glance at the sour-eyed old ladies, "The two of them will be spared the blessings of civilization!"

That's no simple celebration of drink. It is Ford's indictment-leveled in many of his films, particularly the brilliant The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance -- against the modern world, with its sterile rationalism, and its technological wonders put to the procurement of physical safety and comfort. That world is the precondition, too, for feminism, but, at least in Ford's vision, really strong and dangerous women reject it, too.

Meeting in Conflict & Love

In his world, which is I think the true world, men and women are elemental realities, meeting in conflict and in love. Either one of these is potent enough to shake the earth -- or to bring upon earth that tender and most shattering being of all, a human child. |

Always in the movies of John Ford, men and women move like titans of ancient epic, forces that make scientific and sociological analysis look as petty and ineffectual as a city boy in a bow tie. It is dangerous to marry a man, dangerous to marry a woman; just as it is dangerous to tread upon holy ground. A man, in the world of John Ford, would no more pretend to "marry" another man than he would dress up an Indian chief in feathers and loincloth to have him dance in front of children at the local museum. In his world, which is I think the true world, men and women are elemental realities, meeting in conflict and in love. Either one of these is potent enough to shake the earth -- or to bring upon earth that tender and most shattering being of all, a human child.

And perhaps there never was a director who better understood the cosmic significance of the child. In the last shot of The Quiet Man, after a rollicking comic epic of love and stubbornness and sacrifice and forgiveness, Mary Kate watches as Sean is in the kitchen garden he has dug for her, planting potatoes. Potatoes, Sean once told her, were not the things he most wanted to plant. "And what would that be?" she asked, with a scornful toss of her head. "Children," said he.

It is John Wayne here too, with Maureen O'Hara; but they have only recently been married, and she has spent the whole movie denying him her body, because he would not fight her brother for the portion of her dowry, her "things," which her brother spitefully refused to give her.

But now, after celebration and strife -- after he has had to fight his wife and fight for his wife, Sean Thornton looks up to see her smiling at him, and inviting him with a wave of her arm to come into the cottage, in broad day. There they go, arm in arm, to do the brave and holy thing, in that brave and holy place called the bed. The child, we are made to know, will be on the way.

A Sense of the Holy

Somehow, just as the holy is dangerous, so a life open to the danger of love and war, or hardship and celebration, touches upon the holy. Hugh Morgan, the boy in How Green Was My Valley, saves his mother from drowning in an icy stream -- after she had just promised a group of angry men that she will kill with her bare hands anyone of them who harms her husband. Hugh overcomes the paralysis that sets in, and then learns to fight the bullies at the school his father sends him to. When he has finished at that school, his father asks him if he wants to go to Cardiff, to learn to be a doctor or a lawyer.

It is the father's great ambition. But Hugh, with a sense of the holy, and a loyalty that puts to shame all petty considerations of utility, replies that he wants to go down into the coal mine with his father and his brothers. He wants to be a man like them. In almost the final scene, after a cave-in, we see the boy on the lift from the mine shaft, cradling the head of old Mr. Morgan in his lap. "Men like my father can never die," says the narrative voice. "They are with me still."

Is not the converse also true, perhaps? Consider a life shielded from the elements. I don't mean only the wind and the sun and the rain, though a life shut away from those is already paltry enough. I mean the elements of manhood and womanhood; of the cry of the child that comes to destroy your old world and make it new; of people drunk with grief or drunk with joy, burning their own houses down like the rejected Tom Doniphon, the man who really shot Liberty Valance, or stomping around the hay of a barn floor to celebrate a wedding, as in Drums Along the Mohawk.

Paltry Safety

But what a bracing thing it is instead, to meet young people who are really young, and committed to the faith of their fathers! Those young people are here among us. They are still only a few; but they are dangerous. |

Imagine a dis-imaginative life. Imagine central planning and the technocratic management of all things human, or rather suffer it to sweep away the possibility of imagining. Imagine the universal reservation.

Imagine the churches themselves turning away from the net and its great haul of fish on the stormy Sea of Galilee. Imagine them turning to another net, a so-called safety net, stitched up big enough to catch everyone in its meshes, but letting the essence of charity slip through. Think of the committees, the bureaucratic language of the modern prayer.

Think of the interchangeability of man and woman, as one drab shirt is interchangeable with another. Think of Christians "planning" children, or rather planning not to have children, because having one would knock some posts out of the picket fence.

Think of the new commandments. Thou shalt not adore. Thou shalt not celebrate with abandon. Thou shalt not honor. Thou shalt not fight. Thou shalt not live under the law of God, but within the parameters of thy keepers.

Is it possible, I am wondering, that the paltry safety of modern life is itself to blame for our insensibility to the holy? Or rather, whether our almost obsessive desire to insulate ourselves from risk (with even our debauches made "safe" by barriers or pills) also insulates us from the most dangerous of our enemies, that is, the love of God? John Ford, I believe, looked upon the weakling world we had made for ourselves, and he spat. Someone else did that too, if I remember, in the Book of Revelation.

Let The Go Outdoors

But what a bracing thing it is instead, to meet young people who are really young, and committed to the faith of their fathers! Those young people are here among us. They are still only a few; but they are dangerous.

I think I see it in their eyes, the cheerful defiance that moved the best of the protesters in my generation, but a defiance not about to pad itself round with the comforts of the flesh. They will be the men and women to set their stagecoaches to rumble along the dry ruts of plains and deserts more barren than anything John Ford's wagon masters ever faced. They will have the wreck that used to be the United States, and the wreck that used to be Europe.

Let them go outdoors, then. I see them in my imagination, celebrating in the public squares, when everyone about them has forgotten the difference between a celebration and a debauch. I hear them singing together, when everyone else has forgotten that there is anything to sing about. I see them cheerfully being themselves, men being men and women being women, with their gangs of children hollering about them, climbing trees and getting into everything, as they should. I hear them pray in solemn unison, while the world looks away abashed. Then they laugh with real mirth in their hearts, while the world looks askance in envy.

The churches may collapse into social clubs or philanthropic dispensaries or rubble. These men and women will have real communion, and will love their neighbors in truth. They will know the holy.

I see them coming over the ridge. Wagons, ho!

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen, "The Unquiet Men." Touchstone (June, 2009): 9-11.

Reprinted with permission of the author, Anthony Esolen.

Touchstone is a Christian journal, conservative in doctrine and eclectic in content, with editors and readers from each of the three great divisions of Christendom -- Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox. The mission of the journal and its publisher, the Fellowship of St. James, is to provide a place where Christians of various backgrounds can speak with one another on the basis of shared belief and the fundamental doctrines of the faith as revealed in Holy Scripture and summarized in the ancient creeds of the Church.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2009 Touchstone