William Kurelek: Painter and Prophet

- MICHAEL O'BRIEN

"Michael O'Brien explodes old caricatures and intelligently articulates the theological nuance and empathy that lay at the heart of William Kurelek's moral and artistic worldview. ...we cannot but be moved by the depth of understanding that O'Brien brings to this modern prophet." - Andrew Kear, Curator of Historical Canadian Art, Winnipeg Art Gallery, and co-author of the exhibition catalogue "William Kurelek: The Messenger (2011)"

|

A great mystery lies at the heart of every life. Biography, as it approaches the mystery in search of understanding, should go carefully and reverently. At best it can offer intuitions, flashes of insight. The writer is, after all, describing a geography of the soul, an entire universe, equipped only with the crude instruments that come to hand.

Biography fails when the researcher, blithely unaware of his own prejudices, sets forth in pursuit of knowledge of his subject. An ocean of facts can be coloured by opinions and values, and by the selectivity implicit in the author's subconscious perceptions of the shape of reality. In the process a great deal of truth can be lost. The sympathetic, the hostile, or the ambivalent biographer faces the identical problem, for the truth of a life is deep and difficult to grasp.

Some lives offer us a plenitude of meaning, communicated to us through their creative works and their own self-reflections. Kurelek's autobiography, Someone With Me, and those of his art books containing autobiographical elements, tell us much about him. And yet a person writing about himself can remain unaware of the full significance of his own labours, his sacrifices, his greatness, and his weakness. In this regard, biography can be of some assistance, as long as we keep in mind the essential mystery. I have tried to express here a sense of the person he was, impelled by a profound respect for him while retaining, I hope, a certain healthy caution about my own interpretations. Though I came to know him personally only during the final year of his life, everything about the conversations we shared, and about his presence, amply confirmed his writings. In this book, my own small piece of a much larger mosaic, I have frequently quoted from his autobiography in the hope that his own words, combined with his art, will impart a greater sense of who he was.

He was an intensely private man, introverted, shy, self-effacing. And yet he could be astonishingly candid when relating details about his interior wounds, sins, and his long struggle for mental and spiritual health. A person who dares to enter the public arena in such a naked condition exposes himself to attack and misinterpretation. This was the risk Kurelek knowingly took in his desire that his sufferings might be an encouragement for others. He spoke as a witness, as a sign of contradiction and a sign of hope, at a period of history when it seemed that people were no longer interested in the truths that had rescued him.

That he was a great artist is beyond doubt. That he was a man of prophetic gifts is often denied, when it is not ignored altogether. It should be remembered that the artist and the prophet are human beings — with all the frailty this implies — called to deliver a word to a people who do not hear, do not see. Such lives are often heroic, and especially so when the subject is at once an artist and a prophet. William Kurelek's struggle to reconcile those two absolutes has left an indelible mark upon his times.

Stranger and Sojourner

Beloved, you are strangers and in exileâ¦

(1 Peter 2:11)

In 1950 the young painter William Kurelek was hitch-hiking to Mexico where he hoped to be admitted to an art school. Caught at night in the chilly Arizona desert, he crawled under a low road-bridge and lay curled up on the bare ground. In his autobiography, Someone With Me, he relates what then occurred as one of the seminal religious experiences of his life. Unsure if he was fully awake, he became aware that he was not alone.

He appeared to be a person in a long white robe and he was urging me to rise. "Get up," he was saying. "We must look after the sheep or you will freeze to death." I obeyed and set off at a near run down the road shaking violently with the chill.[1]

The incident occurred not, as one might suppose, during a period of religious fervor, but unexpectedly in the midst of his professed atheism, after an indifferent religious upbringing. The vision was a sign that he would not understand until after his conversion to Catholicism seven years later. In the intervening years he would plunge into the disintegration of mental illness and the moral chaos of the modern world. While many successful artists of his generation were preoccupied with power, cultivating self-images as protean beings, Kurelek's experience of life was a constant plunge into weakness of various kinds, even to the point of feeling that he was "nothing." This would prove to be, however, a condition that gradually matured into true poverty of spirit. Throughout his life he knew firsthand what it was to be despised and rejected by men, to be a man of sorrows and familiar with grief. He was like us in all things, including sin. And if he was conformed to the sufferings of Christ long before he found a personal faith, it was in order that he might experience the resurrection offered to all, even the most devastated, that he might speak with authority about the mercy of God. While other artists were promoting secular salvations, while "we were all going astray like sheep," he was undergoing a discipleship that prepared him to be a faithful shepherd. It pleased the Lord to crush him with suffering in order that he might not be destroyed by the fame that would come to him in torrents. Because of that early crucifixion he remained a servant and became a prophet.

|

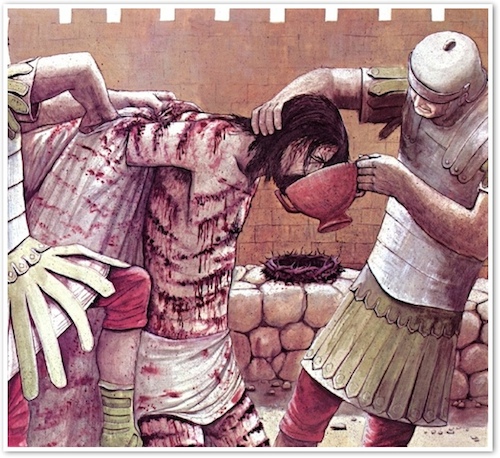

Painting from The Passion of Christ Series, 1950

|

Saint Paul reminds us that the prophetic gift is limited (1 Corinthians 13:8). Prophecy is imperfect because prophets are imperfect. Like all men, they emerge from specific landscapes and histories; they are formed by their times and damaged by sin. It is their difficult calling to proclaim visions of wholeness while remaining conscious of their own incompleteness; to proclaim the realities of the Promised Land while dwelling in exile.

The homelessness of man is a universal awareness. The pagan philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius had described it when he said, "As for life it is a battle and a sojourning in a strange land." The young Kurelek had an intrinsic understanding of the aphorism. He was born in a "shack" northeast of Edmonton in 1927, the eldest child of Dmytro and Mary Kurelek, and was raised in the midst of the Great Depression. His father had emigrated from the Ukraine after the First World War. From earliest memory Dmytro had grown up in a climate of disruption. He was forced to end his education in the third grade because of the war, and from then until his emigration he was a witness to frequent violence. He was a born story-teller and later recounted experiences such as loading soldiers' bodies on a wagon after battles. He became a smuggler and was beaten by border patrols and jailed before he finally managed to escape. He arrived in Canada at the age of nineteen with seven dollars in his pocket and the clothes on his back. He also brought with him a bitterness against his family in the Old Country and a smouldering anger against the injustices of life.

Dmytro Kurelek was the key figure in his son's life. A strong and hardworking man, he and his wife Mary, a second-generation Ukrainian-Canadian, were at work in their fields the morning following their wedding party. For them, life was a struggle, life was battle. Dmytro especially saw threats all around him: weather, neighbours, stubborn farm animals, or the imperfections of his children. He made enemies easily and kept few friends. He was a "displaced person" to the very roots of his soul, and he passed on a sense of exile to his eldest son.

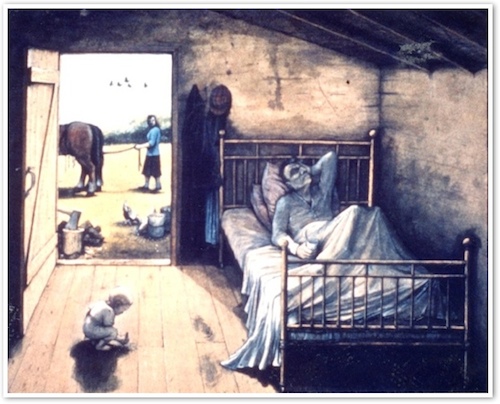

One of William's earliest memories has been recorded in the 1964 painting, Illness (see page 17). Severe stomach pain kept his father incapacitated during the summer of l928. His pregnant wife worked the land alone while he watched the one year-old William. In the painted memory, Dmytro writhes in agony on a bed while through an open door Mary can be seen leading a horse. The child plays on the barren floor, while just outside chickens peck in the dust beside a bloody chopping block.

|

Illness, 1964

|

There was a great deal of anger in the household. The parental attitude was that children were to be punished, not just for "being bad" but for making mistakes, for fears, for sickness, for lacking vigilance in a dangerous world. The six younger children were light-hearted by nature and took this mostly in their stride. William, the sensitive eldest, suffered intensely. He was occasionally kicked in the backside but most often mocked for being "useless," "weak," and "deaf." He retreated into himself and eventually became almost totally silent.

As a young child he began to suffer hallucinations. A huge vulture would perch over his crib, threatening to peck out his eyes. Vision was of great importance to the boy. The family was unaffectionate in those early years, and touch was not a sense used to express love. Hearing was the channel through which he received mockery. Sight, therefore, became a prized possession — he could gaze into creation and find there the joy that was lacking at home. The theme of vision was central in Kurelek's life, long before he discovered his startling power to recreate what he had seen. In later years, before his conversion, he often experienced psychosomatic eye pain and terror of losing his sight.

Kurelek's sense of alienation increased when he was sent to school knowing only a little English. His chattering in Ukrainian was met with laughter and derision. He devotes a large section of his autobiography to the bullying he suffered at grade school. In the early edition of the book he tells with a vivid sense of recall the names and exact words of his tormentors. He describes himself as "hypersensitive" in those years. He was excessively timid and lacking in courage at school, where a sense of social inferiority kept him the victim of "cruel sport."...

Endnote:

- Kurelek, William, Someone With Me (Niagara Falls, Ontario: Niagara Falls Art Gallery, 1988), p. 254. Originally published by the Centre For Improvement of Undergraduate Education, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 1973. All quotations of William Kurelek, unless otherwise attributed, are taken from Someone With Me.

|

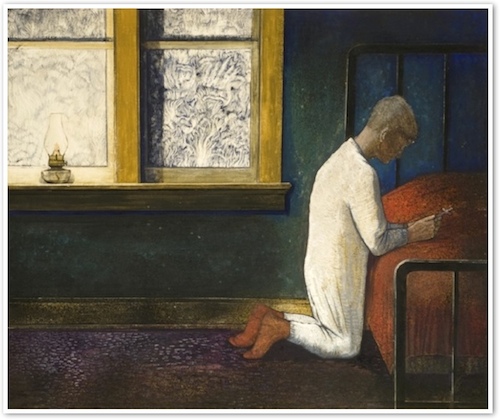

Winter Windows and Praying Boy, 1951

|

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Michael D. O'Brien. "Preface." & "Stranger and Sojourner." excerpt from William Kurelek: Painter and Prophet (Ottawa, ON: Justin Press, 2013): 10-11, 12-17.

Reprinted with permission from Justin Press.

The Author

Michael D. O'Brien is an author and painter. His books include The Father's Tale, Father Elijah: an apocalypse, A Cry of Stone, Sophia House, Theophilos, Island of the World, Winter Tales, Voyage to Alpha Centauri, A Landscape with Dragons: the Battle For Your Child's Mind, Harry Potter and the Paganization of Culture, and William Kurelek: Painter and Prophet. His paintings hang in churches, monasteries, universities, community collections and private collections around the world. Michael O'Brien is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center. Visit his web site at: studiobrien.com.

Michael D. O'Brien is an author and painter. His books include The Father's Tale, Father Elijah: an apocalypse, A Cry of Stone, Sophia House, Theophilos, Island of the World, Winter Tales, Voyage to Alpha Centauri, A Landscape with Dragons: the Battle For Your Child's Mind, Harry Potter and the Paganization of Culture, and William Kurelek: Painter and Prophet. His paintings hang in churches, monasteries, universities, community collections and private collections around the world. Michael O'Brien is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center. Visit his web site at: studiobrien.com.