Sheen and Hiroshima

- DR. CHRISTOPHER SHANNON

The dropping of an atomic bomb on Japan on this date in 1945 provides an opportunity to consider how the unthinkable so often becomes thinkable and doable in the context of competing goods rather than through a direct embrace of evil.

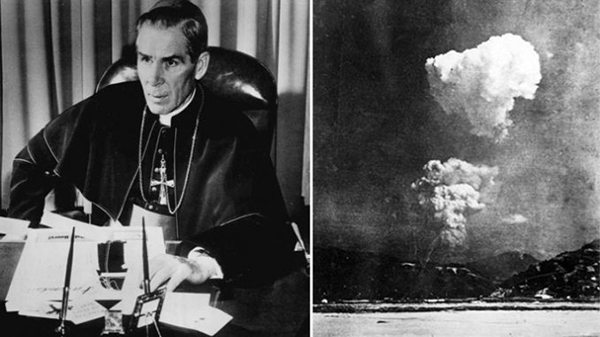

Left: Bishop Fulton J. Sheen in October 1956 (ABC Radio, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons). Right: The Hiroshima atom bomb cloud about 30 minutes after detonation (George R. Caron, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

Left: Bishop Fulton J. Sheen in October 1956 (ABC Radio, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons). Right: The Hiroshima atom bomb cloud about 30 minutes after detonation (George R. Caron, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

These days there is no shortage of doomsayers. Many across the political and religious spectrum feel a profound sense of disease and uncertainty, even fear, about the present state of world affairs. Despite a shared sense of crisis, there is very little agreement on the source of this crisis. Those of a more conservative or traditional orientation often find the source in the great upheavals of the 1960s.

I would like to begin this column with an observation by a traditional Catholic thinker reflecting on the 1960s in 1974, while these changes were still fresh:

See how much the world has changed? Now, what made it change? I think maybe we can pinpoint a date: 8:15 in the morning, the sixth of August, 1945. Can any of you recall what happened on that day? ... it was the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima in Japan. When we flew an American plane over this Japanese city and dropped the atomic bomb on it we blotted out boundaries. There was no longer a boundary between the civilian and the military, between the helper and the helped, between the wounded and the nurse and the doctor, between the living and the dead—for even the living who escaped the bomb were already half-dead. So we broke down boundaries and limits and from that time on the world has said 'We want no one limiting me'. So that, you people have heard the song, you've sung it yourselves: 'I gotta be me, I gotta be free'. We want no restraint, no boundaries, no limits. Have to do what I want to do. Now let's analyse that for a moment. Is that happiness: I gotta be me, I've got to have my own identity?" (This quote and my later reference to Sheen come from Zac Alstin, "Horror of Limitless Freedom: The Moral Fallout of the Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki".)

The author of this reflection: Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen. I admit that despite my own sympathy for sweeping synthesis, the direct line from Hiroshima to cultural revolution seems at first glance a bit of a stretch. Still, entering the anniversary month of Hiroshima in a time of apparent crisis, it seems worth taking a second glance at Sheen's provocative reflection.

The notion that actions taken during World War II sowed the seeds of our current discord is certainly counterintuitive. Across the range of possible positions in today's culture wars, few would see the World War II era, the age of "the greatest generation," as anything other than a time of unprecedented unity; moreover, Americans were united in the most just of all possible causes, the defeat of Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. Catholics, lay and clerical, pledged their full support for "the Good War" and Catholic participation did much to integrate Catholics into the mainstream of American national life.

Long before Hiroshima, however, the undeniably just purpose of the war—the ad bellum—obscured what for Catholics should have been the deeply troubling nature of the conduct of the war—the in bello. A revolution in airplane technology had transformed air warfare from the romantic, mano a mano biplane dogfights of World War I into the massive bombing campaigns that gave a distinct and unprecedented character to conduct of the World War II. The practice, known at the time as "obliteration bombing," targeted not soldiers or isolated military installations, but whole cities—which included "military" targets such as arms factories but also unavoidably the civilian populations surrounding those factories. Scholars such as David Bell see the rise of "total war" as early as the French Revolution, yet World War II saw a technological revolution in the efficiency with which civilian populations could be obliterated.

The indiscriminate slaughter of civilians had, in fact, been an accepted war policy for years prior to Hiroshima. Wilson D. Miscamble, C.S.C.'s The Most Controversial Decision: Truman, the Atomic Bombs and the Defeat of Japan (Cambridge University Press, 2011), is excellent history but oddly, or ironically, titled: Miscamble shows that in moral terms there was actually very little controversy over the decision to use the bombs once Truman and his staff were confident that they would actually work. Truman and most of his advisors saw the atomic bomb as simply a bigger, more destructive version of older bombs, still using TNT as a quantitative, rather than qualitative, point of comparison: "Little Boy," the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, carried the destructive power of 15,000 tons of TNT. The only moral calculus guiding the decision to drop Little Boy (and later "Fat Man" on Nagasaki) was the belief that the bombs would save lives by forcing Japan to surrender, obviating the need for an invasion that would have cost many more lives than lost at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined.

In 1947, then Msgr. Fulton J. Sheen likened such a utilitarian calculus to Hitler's earlier justification for the bombing of Holland. True, by 1947, Sheen was not alone in his outrage and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had indeed become "the most controversial decision." Several years later, the Oxford Catholic philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe famously protested the university's decision to grant Truman an honorary degree. Truman stood by his decision for the rest of his life, yet was deeply troubled by the loss of civilian life in the bombings. This response is, on the one hand, understandable, yet also curious: had not civilian casualties long been accepted as simply part of the nature of modern war? Had not the "conventional" firebombing of Tokyo killed more than the two atomic bombs combined? Perhaps Hiroshima and Nagasaki were simply a powerful symbol or synecdoche for all that had gone before, a transformation that could only be appreciated after the heat of the battle and the single-minded focus on victory had subsided.

Consider how the unthinkable so often becomes thinkable and doable in the context of competing goods, rather than through a direct embrace of evil.

Catholic theologians needed no such hindsight. In 1944, John C. Ford, S.J., published an article, "The Morality of Obliteration Bombing," in the Jesuit journal Theological Studies. Ford assesses Allied policy with respect to the bombing of enemy cities and judges it nearly impossible to reconcile with traditional Catholic teaching on the taking of innocent life, understood as the lives of non-combatants. His argument is subtle and multi-facetted, much broader than a simple exercise in technical theology. He begins with the words of Allied leaders themselves and notes a dramatic change: in 1940, Churchill condemned the German bombing of civilians as an "odious form of warfare"; by 1942, England had adopted the policy as their own and Churchill would go on to vow that there are "no lengths to violence to which we will not go."

What was unthinkable had become thinkable and doable. The bombing continued even when evidence suggested that it was not significantly undermining the industrial capacity of Germany to make war. Once adopted, the practice found its rationale in revenge and the infliction of maximum human suffering. Allied leaders felt no need for moral or theological justification for their actions.

Catholics do need such justification and Ford goes on to consider possible moral justifications for Allied policy. First, by the principle of double effect, the slaughter of civilians could be excused as a secondary consequence of the morally legitimate act of targeting enemy factories; he ultimately rejects this as the proximity of civilians to factories and the nature of obliteration bombing render it impossible to speak of civilian deaths as a secondary effect. Second, by the principle of proportionality, the good achieved by the bombing (bringing a swift end to the war) outweighs the evil (civilian deaths); he rejects this as well, arguing both that there is no evidence that the bombing is shortening the war and that the good it may achieve is speculative while the evil it inflicts is real.

Many of Ford's arguments would have been well known to his fellow moral theologians. Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the article is the way in which Ford struggles with the clear disconnect between Allied policy and Catholic theology, at times dismissing possible defenses of Allied practice as mere sophistry, while at other times insisting on tremendous caution and restraint in making any final judgments that might force American Catholics to choose between their country and their faith. Ford was no pacifist; he was a patriotic Catholic American who identified the tragic choice facing Catholics but could never bring himself to make the choice himself, much less counsel others to do so.

Later in his life, he faced another tragic choice. As John McGreevy has shown in his informative Catholicism and American Freedom (W.W. Norton & Company, 2004), Ford was the leading defender of the Church's teaching on artificial birth control in the decades leading up to Humanae Vitae; in this instance, facing tremendous social and political pressure for Catholics to go along with the rest of America by embracing contraception, Ford publicly and defiantly affirmed the Church's teaching. Sadly, most American Catholics followed the precedent set by World War II-era patriotism.

I am not quite sure if the career of John Ford, S.J., proves Fulton Sheen's link between Hiroshima and cultural revolution. It does, however, provide an opportunity to consider how the unthinkable so often becomes thinkable and doable in the context of competing goods, rather than through a direct embrace of evil. I am certainly happy that the United States won the Second World War and did so without the tremendous loss of life—American, Japanese and Russian—that would have accompanied an invasion of Japan. At the same time, I am sad that this victory came through years of committing intrinsically evil acts.

In the face of the tragedy of the Second World War, perhaps we could have at least done some kind of public penance. August 6 could have become a day of national (or at the very least, Catholic) reparation for the sins of total war. It did not. It is also never too late, especially considering how the disciplining of Catholics who publicly violate Church teaching is so very much in the news these days. At the very least, we can be thankful that the United States has not used nuclear weapons since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Still, sanitized memories of the Good War led the United States to repeat its tragedy in the Cold War, often with the full support of American Catholics. In Vietnam, a comparatively "limited" war, the U.S. bombing tonnage exceeded that of the Pacific theater of World War II.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Christopher Shannon. "Sheen and Hiroshima." Catholic World Report (August 6, 2023).

Dr. Christopher Shannon. "Sheen and Hiroshima." Catholic World Report (August 6, 2023).

Reprinted with permission from Catholic World Report.

The Author

Dr. Christopher Shannon is a member of the History Department at Christendom College, where he interprets the narrative of Christian history from its foundations in the Old Testament and its heroic beginnings in the Church of the Martyrs, down through the ages to the challenges of the post-modern world. His books include Conspicuous Criticism: Tradition, the Individual, and Culture in Modern American Social Thought (Johns Hopkins, 1996), Bowery to Broadway: The American Irish in Classic Hollywood Cinema (University of Scranton Press, 2010), and with Christopher O. Blum, The Past as Pilgrimage: Narrative, Tradition and the Renewal of Catholic History (Christendom Press, 2014). His book American Pilgrimage: A Historical Journey through Catholic Life in a New World was published in June 2022 by Ignatius Press.

Copyright © 2023 Catholic World Report