Taboos and tattoos

- FATHER TADEUSZ PACHOLCZYK

On TV these days, we're seeing more and more programs about "body art" and tattoo design.

|

Despite the apparent widespread acceptance of the practice, there are several problems with tattooing that go beyond the sanitary issues, disease transmission, and unclean inking needles that can be found in second-rate tattoo parlors.

Tattoos, as some who have gotten them have recognized, have negative associations. An article in the Dallas Morning News a few years ago chronicled the story of a young man named Jesus Mendoza, who was "going to great lengths to remove the six tattoos that hint at his erstwhile gang involvement . . . He feels branded. 'It's the stereotyping,' he said. 'The question is: What do you think when you see a young Hispanic male with tattoos? You're going to think gangs. And I think that, too, now.'"

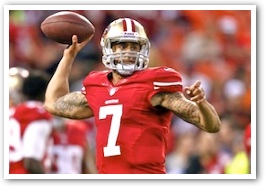

Similar branding concerns were raised in a recent column by David Whitley about San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, whose arms and back are full of tattoos. "NFL quarterback is the ultimate position of influence and responsibility," he wrote. "He is the CEO of a high-profile organization, and you don't want your CEO to look like he just got paroled."

That branding communicates a message that can make life more difficult for those who have tattoos. It should come as no surprise that employers often associate tattooed workers with "reduced productivity" and may show a preference for untattooed employees in hiring or promotions.

Exhibitionism

Even for the vast majority of tattoo recipients who have no connection with gangs or an indolent lifestyle, a psychological issue is raised by the way they seem to serve as marks of vanity. Placing tattoos in positions where they can hardly be missed — on the neck, the forearms, or even the face — can play into a disordered desire to be flamboyant, disruptive, and self-seeking with our bodily image. One young woman, tattooed with the image of a fairy having "stylized butterfly wings, in a spray of pussy willow" expressed her sentiments this way: "I am a shameless exhibitionist and truly love having unique marks on my body."

These questions about vanity lead to similar concerns about modesty. Modesty in its essential meaning involves the decision to not draw undue attention to ourselves. Tattoos and body piercings most definitely draw attention, and often may be desired for precisely these immodest reasons. We ought to dress modestly, in part, to prevent others from being attracted to us out of a mere "focus on body parts."

One aspect of dressing modestly is to make sure everything needing to be covered is, in fact, adequately covered. Placing tattoos in unusual positions on the body may tempt us to dress immodestly so as to assure that the tattoo is visible and exposed for general viewing, in the same way that elective breast augmentation may tempt some women to lower their necklines.

Tattoos, chosen as a permanent change to one's own body, may also suggest issues with psychological self-acceptance. One young woman wanting to get a tattoo expressed her desire to look "edgier," after concluding that she was just too "squeaky-clean" looking.

The body as a work of art

The simple beauty of the human body constitutes a real good and that basic goodness ought to be reasonably safeguarded. Permanent, radical changes to the human body can indeed signal an unwillingness to accept its fundamental goodness, and in certain cases of very radical tattooing and body piercing, one can even discern a subtle form of self-rejection and self-mutilation.

Pop musician Robbie Williams remarked: "I wish it was like an Etch-a-Sketch where I can wipe them all out: it would be nice to have a pure, clean body again."

There is a spiritual dimension involved as well. Russell Grigaitis, who now regrets getting several tattoos in his 20s, argues in a National Catholic Register interview, "God created the body. A tattoo is like putting graffiti on a work of art." He compares it with trying to improve a painting by Michelangelo.

Some argue that there can be good spiritual reasons for getting tattoos. For example, people have gotten Crosses or an image of Jesus tattooed as a sign of permanent commitment to Christ, or a ring or a spouse's name tattooed as a sign of their marital commitment. Yet isn't a personal commitment to Christ or to one's spouse more effectively manifested through the realities of inner virtue and a life of outward generosity than by a tattoo?

It's unsurprising that many who got tattoos in their younger days have grown to regret it later. Pop musician Robbie Williams remarked: "I wish it was like an Etch-a-Sketch where I can wipe them all out: it would be nice to have a pure, clean body again."

The American Academy of Dermatology reported in 2007 that "tattoo regret" is now quite common in the United States. Tattoo removal is a costly and difficult procedure and can leave translucent areas on the skin that never go away. The most effective remedy, of course, is to not seek tattoos in the first place.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Tadeusz Pacholczyk, Ph. D. "Taboos and tattoos." Making Sense Out of Bioethics (December 13, 2012).

Father Tad Pacholczyk, Ph. D. writes a monthly column, Making Sense Out of Bioethics, which appears in various diocesan newspapers across the country. This article is reprinted with permission of the author, Rev. Tadeusz Pacholczyk, Ph. D.

The National Catholic Bioethics Center (NCBC) has a long history of addressing ethical issues in the life sciences and medicine. Established in 1972, the Center is engaged in education, research, consultation, and publishing to promote and safeguard the dignity of the human person in health care and the life sciences. The Center is unique among bioethics organizations in that its message derives from the official teaching of the Catholic Church: drawing on the unique Catholic moral tradition that acknowledges the unity of faith and reason and builds on the solid foundation of natural law.

|

|

The Center publishes two journals (Ethics & Medics and The National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly) and at least one book annually on issues such as physician-assisted suicide, abortion, cloning, and embryonic stem cell research. Educational programs include the National Catholic Certification Program in Health Care Ethics and a variety of seminars and other events.

Inspired by the harmony of faith and reason, the Quarterly unites faith in Christ to reasoned and rigorous reflection upon the findings of the empirical and experimental sciences. While the Quarterly is committed to publishing material that is consonant with the magisterium of the Catholic Church, it remains open to other faiths and to secular viewpoints in the spirit of informed dialogue.

The Author

Father Tadeusz Pacholczyk earned a Ph.D. in Neuroscience from Yale University. Father Tad did post-doctoral research at Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School. He subsequently studied in Rome where he did advanced studies in theology and in bioethics. He is a priest of the diocese of Fall River, MA, and serves as the Director of Education at The National Catholic Bioethics Center in Philadelphia. Father Tadeusz Pacholczyk is a member of the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center. Go here to read more by Father Pacholczyk.

Father Tadeusz Pacholczyk earned a Ph.D. in Neuroscience from Yale University. Father Tad did post-doctoral research at Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School. He subsequently studied in Rome where he did advanced studies in theology and in bioethics. He is a priest of the diocese of Fall River, MA, and serves as the Director of Education at The National Catholic Bioethics Center in Philadelphia. Father Tadeusz Pacholczyk is a member of the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center. Go here to read more by Father Pacholczyk.