John Paul II and Taking the Discipline

- FATHER ROBERT BARRON

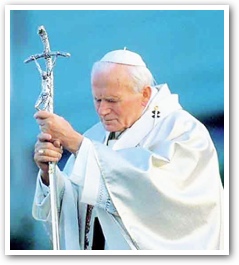

Perhaps you were startled to learn recently that Pope John Paul II regularly practiced the form of mortification called taking the discipline, that is to say, striking his body with a whip.

|

Apparently he hung the disciplinary belt in his closet, along with his vestments, and never failed to take it with him, even when he went on vacation. He also, we learned, sometimes slept on the hardwood floor of his bedroom as an ascetic practice, purposely messing his sheets and blanket in the morning so as not to draw attention to what he had done.

I realize that activities such as these can strike many contemporary people as bizarre, perhaps even as the fruit of psychological disorders, complexes, and repressions. Though the author who reported these things did so in order to convince us of John Paul's sanctity, some today might, because of them, actually think less of the late Pope. I thought that these revelations might be a good occasion to reflect more deeply on the typically Lenten practices of mortification and asceticism.

I would first observe that "taking the discipline" was hardly something unique to John Paul. Many of the great masters of the spiritual tradition over the centuries both practiced it and recommended it, and it was a staple of the asceticism of most of the mainstream religious orders up until the time of Vatican II. A second observation is that taking the discipline should never be confused with a wanton display of masochism: the instrument in question was usually a rope with a few small knots tied in it, and the actual physical pain involved was usually minimal. Da Vinci Code fantasies about vicious self-flagellation should be set aside.

But what precisely is the point of this unusual practice? First, it is a means of imitating Christ by participating in his suffering. The goal of the spiritual quest is to allow Jesus to live his life in us fully. St. Paul said, "it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me." This means that we must strive to conform ourselves to Jesus' humility, his compassion, his joyful prayer, his identification with sinners, his teaching, his manner of thinking and feeling, and his vicarious suffering. By taking upon himself unmerited suffering, Jesus atoned for the sins of the world.

We can enter, however imperfectly, into this dynamic by accepting – for our own sins or those of others – some physical or psychological discomfort. Thus St. Dominic recommended that one pray with one's arms stretched out for a long period in the attitude of the crucified Lord, St. Benedict urged his monks to fast frequently, and St. Antony endured myriad hardships in the solitude of his desert hermitage. Again, this isn't masochism but spiritual participation, an attempt, as Paul put it, "to make up in our own bodies what is still lacking in the suffering of Christ." A corollary to this principle is what Charles Williams called "co-inherence," the idea that we are all, at the deepest metaphysical level, connected to one another. Because we are so inextricably bound together, we can bear each other's burdens, one person, as it were, offering his suffering on behalf of someone else.

A second spiritual reason for John Paul's practice is the legitimate disciplining of the body. As I have often argued, Catholics are not dualists or puritans. We don't think that the flesh is, in itself, sinful or problematic. However, we know that the desires of the body have become, through the fall, disordered. We experience the fact that they are no longer consistently subordinated to reason and that they can consequently appear in exaggerated form or assert themselves disproportionately.

Merton said that we fast, from time to time, from food and drink and sex precisely so as to allow the deeper spiritual hungers to surface and be satisfied. |

Thomas Merton commented that the needs of the body – for food, drink, sleep, and sex – are like insistent children that pester us and demand to have their way. Just as children have to be disciplined lest they come to dominate the household, so the desires of the flesh have to be curtailed, limited, lest they come to monopolize all of one's energies. Merton said that we fast, from time to time, from food and drink and sex precisely so as to allow the deeper spiritual hungers to surface and be satisfied. Now the use of the discipline is an extreme and very pointed instance of this practice. It is a vivid reminder to oneself that the pleasure of the body is not one's determining and ultimate good.

I realize that some readers might still be balking at this point, wondering whether this particular discipline still seems rather over the top. But stop and consider for a moment the activities that go on every day in the typical work-out center. People labor away on stationary bikes, stair-masters, eliptical machines, and treadmills; they sweat their way through pull-ups, push-ups, dead-lifts, and kettle-bell routines. In all sorts of ways, they discipline their bodies so as to overcome the natural tendency toward laziness and self-indulgence. More to it, these same people most likely deny themselves all sorts of pleasurable foods, resisting powerful cravings. And all of this punishment is in service of a healthier body. Why can't certain forms of corporal discipline be in service of the far more important health of the mind and spirit?

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Robert Barron, "John Paul II and 'Taking the Discipline'." Our Sunday Visitor (March 15, 2010).

Reprinted with permission of Father Robert Barron.

The Author

Bishop Robert Barron is Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. He is also the founder of Word On Fire. Bishop Barron is the author of Exploring Catholic Theology, And Now I See: A Theology of Transformation, Thomas Aquinas: Spiritual Master, Heaven in Stone and Glass: Experiencing the Spirituality of the Great Cathedrals, Eucharist (Catholic Spirituality for Adults), Priority of Christ, The: Toward a Postliberal Catholicism, and Word on File: Proclaiming the Power of Christ.

Bishop Robert Barron is Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. He is also the founder of Word On Fire. Bishop Barron is the author of Exploring Catholic Theology, And Now I See: A Theology of Transformation, Thomas Aquinas: Spiritual Master, Heaven in Stone and Glass: Experiencing the Spirituality of the Great Cathedrals, Eucharist (Catholic Spirituality for Adults), Priority of Christ, The: Toward a Postliberal Catholicism, and Word on File: Proclaiming the Power of Christ.