What the Notre-Dame fire did to France

- MICHAEL DUGGAN

Notre-Dame is both the soul of France, and the beating heart of Paris. I haven't been there in a long time. This book left me aching to return.

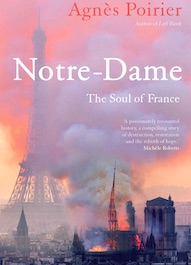

Notre-Dame: The Soul of France

Notre-Dame: The Soul of France

By Agnés Poirier

Oneworld, 240pp, £16.99/$26.95

I lived in northern France for two years in the early 1990s. Among those I knocked around with, in the newspapers I read, and in the films I watched, I don't recall noticing much evidence that the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris was so especially dear to the people of France that it might be called the soul of the nation, as the subtitle of Agnès Poirier's new book has it. Among the great national monuments, I would have thought that the Arc de Triomphe, for one, had greater purchase on French hearts and minds.

On the other hand, as Joni Mitchell sang, you don't know what you've got till it's gone. Until seeing it go up in flames, a nation that prided itself on Enlightenment, rationalism and secularity might easily forget that it still had such a thing as a soul.

The Notre-Dame fire was a visceral experience for Paris-resident Poirier: binoculars in hand, she punched the air upon realising that the stained-glass windows would survive. Her book opens with a gripping reconstruction of the events of April 15, 2019, capturing the pounding adrenaline rush as knife-edge decisions were made and brave people worked frantically to save what could be saved.

Poirier then settles into a generous-spirited and accessible historical survey, exploring, chapter by chapter, certain momentous years and phases in the history of Notre-Dame, beginning with its founding amid "a tangle of narrow lanes, open sewers and pigsties". Over and over, we see the tentacles of politics winding themselves around the cathedral. Reading again about the goings-on when it was converted to "The Temple of Reason" during the Revolution and the Terror is gobsmacking. And then comes the drama of de Gaulle taking his place in the choir on the day of liberation, unbowed, unflinching, as bullets ricocheted off the masonry and the Magnificat rang out.

Poirier's account of events since the fire provides an intriguing critique of the cluster of institutions and interest groups, the Church included, that must now cooperate to ensure a successful renewal.

Throughout the book, Poirier pays due respect to the building's Catholic identity. In The Discarded Image, CS Lewis observed that entire buildings in the Middle Ages could amount to "petrified cosmology"; and here Poirier cites the historian Georges Duby's similar remark that the builders of the great Gothic cathedrals were each time erecting "a demonstration of Catholic theology", a "transcription into inert matter" of what the teachers were propounding in medieval universities.

The chapter on the creation and installation of new bells in 2013 is instructive and delightful and will warm the hearts of embattled French Catholics. When Parisians of all stripes stopped to listen to these bells for the first time, they were listening to the voice, as Poirier has it, of a long-distant, pre-revolutionary past. But the author is anxious to claim Notre-Dame as "more than just a cathedral" — as a place of communion and a refuge for all-comers. This is a delicate balancing act. Poirier is passionately French, passionately Parisian. She wishes to do full justice to the profound and beautiful legacy the Catholic Church has placed at the eastern end of the Île de la Cité, but also to everything else the City of Light stands for, much of it a long way removed from the Catholicism that had "stifled French society for centuries".

And then comes the drama of de Gaulle taking his place in the choir on the day of liberation, unbowed, unflinching, as bullets ricocheted off the masonry and the Magnificat rang out.

As such, the fire seems to have somewhat melted (temporarily, at least) previous stark divisions in the French mindset.

Poirier turns once more to Georges Duby to praise the professors of the University of Paris in the 13th century, proclaiming the thinking that led to "human dignity, freedom and goodness". She remembers Victor Hugo's house of exile on Guernsey where, worded in Latin and French, "fiercely progressive republican mottos were interwoven with the author's ardent Catholic faith". She recalls how, when the bells tolled for the dead of Charlie Hebdo, and for the victims of the November 2015 attacks, they tolled "for those who believed in heaven and those who didn't". As long as symbols such as Notre-Dame exist, Poirier reflects, society's link with the transcendental, never completely renounced, can remain,

Meanwhile, when it comes to French attitudes to philanthropy, the fire "changed everything" in a country where "people traditionally rely on the state for almost everything in life". We shall see how that particular shift plays out over the coming years, but, wherever the money comes from, the author, one gets the feeling, wishes to see Notre-Dame (including Viollet-le-Duc's famous spire) restored, not remade.

I was wrong, then. Notre-Dame is both the soul of France, and the beating heart of Paris. I haven't been there in a long time. This book left me aching to return.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Michael Duggan. "What the Notre-Dame fire did to France." Catholic Herald (May 29, 2020).

Reprinted with permission of the Catholic Herald. The Catholic Herald is a London-based magazine, established as a newspaper in 1888 and published in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.

The Author

Michael Duggan writes for the Catholic Herald.

Copyright © 2020 Catholic Herald