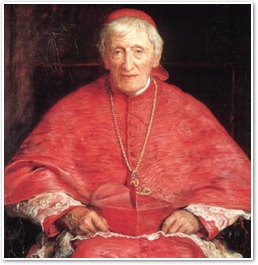

The Personalism of John Henry Newman

- JOHN F. CROSBY

An astute writer on John Henry Newman has remarked that the soon to be saint, "stands at the threshold of the new age as a Christian Socrates, the pioneer of a new philosophy of the individual Person and Personal Life."

This is well said. It singles out Newman's personalism as central to his teaching. Now that Newman is about to be presented to the Church as a saint, and will likely be named a doctor of the Church before long, we naturally want to know more about his pioneering personalism, especially since this aspect of Newman is sometimes overlooked, even by his admirers.

Let's start with his distinction between notional and real assent, a distinction that is absolutely fundamental to his thought.

Suppose I think about my coming death like this: every living being dies, and I will too, for I am a logical part of "every living being." In this way I think about my death from without, for I cast it out there as one of the billions of deaths that occur. I take it as a mere instance of the universal mortality of nature. I am a spectator of my coming death. As a result I give only a notional assent to it.

But suppose that I ignore the billions and think that I — I myself and not any other — will one day die. Suppose that I refuse to universalize my coming death, dissolving it into a mere instance, but rather encounter it in its radical particularity as my death. Then it is that I give not a notional but a real assent to it.

Newman teaches that, of the two modes of assent, real assent is the more properly personal assent. For in notional assent I take myself as merely the instance of a type, and as only one among many, whereas in real assent I take myself as this person and no other. And in notional assent I exercise only an abstract cognition, which does not engage me deeply as person. Whereas in real assent, the waters of my personal existence are deeply stirred. With notional assent I may just yawn at my coming death, whereas with real assent I shudder at the thought of it.

Now Newman thinks that this important distinction is also found in our relation to God. I can know God by way of what he calls the "theological intellect," which is to know Him notionally, or by way of the "religious imagination," which is to know Him really.

Newman once famously said: "I am far from denying the real force of the arguments in proof of a God . . . but these do not warm me or enlighten me; they do not take away the winter of my desolation, or make the buds unfold and the leaves grow within me, and my moral being rejoice." He is saying in effect: what the theological intellect gives me in the way of arguments and proofs is, by itself, not enough, it is barren; it is the religious imagination that really engages me as person and that nourishes me and gives me something to live by.

"…but these do not warm me or enlighten me; they do not take away the winter of my desolation, or make the buds unfold and the leaves grow within me, and my moral being rejoice."

But what exactly is the source of the religious imagination? Newman answers: the promptings of conscience. In the experience of being morally obliged, or in the experience of being ashamed because of some wrong I have done, I encounter the living God in my conscience, I am in His presence. I experience my creaturehood and His sovereignty.

We would misunderstand Newman, however, if we thought that he reasons to God from conscience, as if he took moral obligation as an effect and took God as the only possible cause of the effect. For in that case he would still be exercising only the theological intellect and would not get beyond a notional assent to God. He would lose the personal encounter with God in conscience that is so important to him. It is rather that he discerns God in the experience of obligation; it is a discerning that is more a perceiving than an inferring.

Newman discerns in conscience a being-seen, a being-addressed; in this intersubjective situation he discerns an absolute, divine Other. He experiences in himself "an infinite abyss of existence" that resonates with the divine Other. This encounter is for Newman "the creative principle of religion," the primordial source of the religious imagination. It can give us what the theological intellect cannot give, namely a real assent to God, an assent that touches the heart and empowers us to live a committed religious existence.

Note well: Newman is not proposing to dismantle the theological intellect and to replace it with the religious imagination. He wants only to complete it with the religious imagination. Consider the inspired sermons of Newman, the Anglican no less than the Catholic sermons. They have wrought wonders of conversion in his listeners and in his readers over the years. And the secret of their power, at least in part, is Newman's uncanny ability to convert notional assents into real assents.

Newman saw that many in his congregation had only a conventional, notional assent to the things of faith, and he knew how to breathe an experiential fullness into their assents, not by abolishing the notional contents of faith, but by forming in the minds of his listeners a composite of "notion" and "experience" that was life-giving and life-changing for them.

And the secret of their power, at least in part, is Newman's uncanny ability to convert notional assents into real assents.

And yet Newman has sometimes been suspected of condoning a subversive subjectivism. Some say that with his personalism he makes too much of religious experience. Some say that he prepared the way for the theological modernism in the Church that was condemned by Pope Pius X in 1907.

I would defend Newman like this. It is true that Newman, for all of his roots in the Greek fathers of the Church, is a distinctly modern thinker. We can detect in him something of that "turn to the subject," which is supposed to be the signature of modern thought. For Newman is concerned not only with the objective truth in itself, but with the way this truth is received and lived in the believer.

But this pastoral concern of Newman's, which is very like the pastoral concern of Vatican II, has nothing to do with subverting objective truth. In converting notional assents into real assents and in awakening religious experience, Newman wants to release the transformative power of the truth we already acknowledge. Understood in this way, his personalism enhances the power of his Christian witness and has nothing to do with subjectivism.

Perhaps we could put it like this. It is not subjectivism when I move from a notional to a real assent to my coming death; in fact, in the real assent I enter much more deeply into the truth about my death. Just as little is the move from notional to real assent in matters of religion a lapse into subjectivism; here too we enter by the personalist approach more deeply into the truth about God.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

John F. Crosby. "The Personalism of John Henry Newman." The Catholic Thing (September 14, 2019).

John F. Crosby. "The Personalism of John Henry Newman." The Catholic Thing (September 14, 2019).

Reprinted with permission from The Catholic Thing. All rights reserved. For reprint rights, write to: info@thecatholicthing.org.

The Author

John F. Crosby is Professor of Philosophy at Franciscan University of Steubenville. Professor Crosby is known internationally for his work on John Henry Newman, Max Scheler, Karol Wojtyła, and Dietrich von Hildebrand. Dr. Crosby worked with his son in founding the Dietrich von Hildebrand Legacy Project. He has also made a significant contribution to the area of philosophical anthropology or the philosophy of the human person and has played a major role in the contemporary interest and discussion of that field through his books, The Personalism of John Henry Newman, The Selfhood of the Human Person and Personalist Papers.

John F. Crosby is Professor of Philosophy at Franciscan University of Steubenville. Professor Crosby is known internationally for his work on John Henry Newman, Max Scheler, Karol Wojtyła, and Dietrich von Hildebrand. Dr. Crosby worked with his son in founding the Dietrich von Hildebrand Legacy Project. He has also made a significant contribution to the area of philosophical anthropology or the philosophy of the human person and has played a major role in the contemporary interest and discussion of that field through his books, The Personalism of John Henry Newman, The Selfhood of the Human Person and Personalist Papers.