The Delicate Nest

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

"And this Catholic Church," wrote the scholar and priest, "so weak in herself, so strong in her God, what a spectacle her history presents!

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

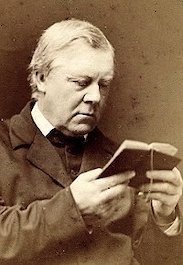

Father Edward Caswall

Father Edward Caswall1814-1878

Only now we behold her, in the very infancy of her existence, tossed by persecution, and almost drowned in blood; but God, who enables the reed to stand before the gale that uproots the oak of centuries — God, whose providence sustains the sea-bird's delicate nest on the foaming wave…" — and he puts down his pen and does not finish the sentence.

"A delicate nest," he says, and his mind returns to a sunny day in September, on the shores of the ocean. He and his beloved wife, Louisa, had gone to the resort town of Torquay. Cholera had ravaged the land. That morning he went to Mass, and when he came back, Louisa was ill. She died that night. She was only twenty-eight years old.

He knew what his brother would think. It was a judgment against him. For he had enjoyed a good living as an Anglican curate, in the diocese of his uncle the bishop, and he gave that all up when he and Louisa had left the English church to commit themselves to the Church of Rome.

"You are seeking to destroy our happy home," said Alfred.

"I must follow my conscience in this matter."

"You are not following your conscience. You are following that self-important knave, Dr. Newman."

"He too must follow where the truth leads."

"Truth?" said Alfred. "You break your faith, and you pledge yourself to a foreign church, and be assured, that church is doomed. What truth are you talking about?"

Edward Caswall, priest and poet, translator and composer of hymns, knew what truth it was, and tried to see God's hand in that day long ago on the coast. Louisa had seen it, if Alfred could not. And he took up his pen again.

In the light of the eternal

Father Caswall was not a great scientist, like the monk Gregor Mendel. He did not rule a nation, like Saint Louis IX of France. He did not found a missionary order, like Saint Ignatius of Loyola. He did not paint the Sistine Chapel, or write the greatest plays in the history of the world.

Yet we ought to see his life as somehow of his age, Victorian England, and not of his age; a man formed by the faith and its history, but whose work, gentle, pious, and touching all features of Christian worship, was the leaven in the dough for his time, and will last as long as English is spoken; the standard-setter for English hymnody, whose greatest influence I am persuaded is yet to come.

After Louisa Caswall died in 1849, Edward determined to seek holy orders as a Catholic priest. He joined the Birmingham Oratory, founded by Newman, and was ordained a priest in 1852, where he lived until his death in 1878. The cardinal was the superior at the Oratory, but he was often absent, and to Caswall would fall the duties of his friend, in addition to his regular oversight of the Oratory's finances.

But we do not know Edward Caswall for his practical skills as a manager. We know him — or we ought to know him — for his hymns.

The Church has her daily office, her prayer-duty, for the eight canonical hours of the day, and for all the seasons and feasts of the year. Each hour, each day, each season, each feast has its song: and so Caswall, classically educated, set himself the task of translating every single one of them into English poetry, more than four hundred pages of hymnody. Here is a stanza from the first, for matins for Sunday:

So, while on this his holy day,

At this most sacred hour,

Our psalms amid the stillness rise,

May he his blessings shower.

Simplicity and clarity were Caswall's strengths, and it is always easy to underestimate them. But in his words we find an awareness that there is always more to the world than we see before us: more beauty, a deeper mystery, and the light of eternity shining quietly upon and through the works of time. Here the priest regards the sea, and remembers his boyhood, and considers the world to come:

The thoughts which my childhood beguiled

Were an emblem, I well perceive how;

As I thought of the sea when a child,

So I think of eternity now.

I stand by the side of its sea,

I gather the shells on its shore;

But its depths are mysterious to me

As the depths of the ocean of yore.

Ever the child

Cardinal Newman once humorously said of his old friend Caswall that he was "half a saint." Saint or not, he was always more than half a child. Sometimes he had the harmless mischief of a child. Here's how the young Caswall began his "Sketches of Young Ladies," which were published along with "Sketches of Young Gentlemen" by Charles Dickens. "We have often regretted," he says, "that while so much genius has of late years been employed in classification of the vegetable and animal kingdom, the classification of young ladies has been totally and unaccountably neglected." For example, there is the Young Lady Who Sings. You'll meet her at a party, and after she drops a hint about Italian food, she will ask you if you are fond of music. "Beware of answering in the affirmative," says Caswall.

His admiration of the fair sex was deep, though, as was his devotion to Mary and to the humanity of Jesus, and that should guarantee that his hymns will be a pattern for authors and composers to come. Look at the first stanza of his lovely Christmas carol:

Sleep, holy babe,

Upon thy mother's breast!

Great Lord of earth and sea and sky,

How sweet it is to see thee lie

In such a place of rest.

Caswall places himself and us there at the manger too:

Sleep, holy babe,

While I with Mary gaze

In joy upon that face awhile,

Upon the loving infant smile

That there divinely plays.

But it is no mere sentimentality. Father Caswall knew, as his countryman Dickens knew, that the Father reveals the Son not to the high and mighty, but to innocents and fools, to those who press upon the gates of heaven like eager children. So we have his fine doxology at the end of a hymn for the Transfiguration:

To Jesus, from the proud concealed,

But evermore to babes revealed,

All glory with the Father be,

And Holy Ghost, eternally.

t is the child's longing in love.

Tenderness amid the Smoke

We hear that we have to tailor the message of Jesus to the audience, but we should never suppose that ordinary people aren't capable of appreciating real beauty, just because they live in a bustling, grimy, ugly industrial city like Birmingham, and were not educated at Oxford, as Father Caswall was. Notice the mingling of tenderness, clear vision, and intellectual strength in his description of the school in Birmingham that he and Newman had founded, staffed by women who volunteered their services. "The unusual sight has been seen," he wrote, "of between thirty and forty boys entirely obedient to the firm but gentle control of a lady's hand." In later years, he said, these children, both boys and girls, would come to treasure the inestimable advantage they had been given, of being brought into contact "with the minds of persons belonging to a sphere above their own."

Is not that what sacred song and poetry should do? Not raise a yawn or a roll of the eyes, but bring us, children as we are, into a spiritual and intellectual sphere far beyond that of the ordinary day? Think of this famous medieval hymn, sweetly translated into English by Father Caswall:

Jesu! the very thought of thee

With sweetness fills my breast,

But sweeter far thy face to see,

And in thy presence rest.

Father Caswall left the world among us gently too. Cardinal Newman would write these words to the priest's sister: "He seems to have felt that he was drawing to his end, for in the middle of the day he began to express his sense of God's mercies in having been so tender and careful of him all through his life, and having kept him from pain during his last illness. He was one of my dearest friends, and is a great loss to us all, for he was loved far and wide round about the Oratory."

I find no fitter way to end than with a few stanzas from a gentle hymn for the close of the day, preparing for the evening of life:

The sun is sinking fast,

The daylight dies;

Let love awake, and pay

Her evening sacrifice.

As Christ upon the cross

His head inclined,

And to his Father's hands

His parting soul resigned,

So now herself my soul

Would wholly give

Into his sacred charge,

In whom all spirits live.

"Into your hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit," said the Lord. We must say so too. Father Caswall has given us the means even to sing it.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: The Delicate Nest." Magnificat (November, 2020).

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: The Delicate Nest." Magnificat (November, 2020).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2020 Magnificat