The Real Issues of the Reformation

- JAMES HITCHCOCK

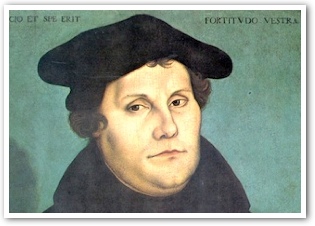

An informed person, asked what lay at the root of Martin Luther's theology, immediately answers, "Justification by faith alone."

|

Martin Luther

1483-1546 |

Since the Second Vatican Council, the Reformation has been approached ecumenically, meaning that both Catholics and Protestants recognize legitimate concerns on each side of the sixteenth-century divide. Non-Catholic historians, for example, now commonly use the term Catholic Reformation instead of Counter Reformation, acknowledging that the forces of reform within the Church were not simply a reaction to the Protestant attack.

Ecumenism leads to an approach to the Reformation that is primarily doctrinal, which identifies the key theological issues that divided the Church in the sixteenth century, then expends great effort trying to understand and resolve them.

An informed person, asked what lay at the root of Martin Luther's theology, immediately answers, "Justification by faith alone." Logically, and in Luther's own mind, this is true. But it is questionable to what extent this was the actual driving force of the Reformation. The doctrine of justification is subtle indeed, provoking fierce arguments even among people who ostensibly share the same beliefs (Jesuits and Dominicans, Calvinists and Arminians). It is likely that relatively few people in the sixteenth century really understood the issue, much less was it the crucial question for most of them.

What then was? In broadest terms, the issues seem to have been the sense of the Church as an oppressively intrusive institution and, much more elusive, what might be defined as the loss of the sacramental sense of reality, of the awareness that the spiritual is mediated through the material, the eternal through the temporal.

The Church was intrusive in many ways. Probably the single most effective weapon the Reformers had was popular resentment of ecclesiastical financial exactions and of the bewildering forest of laws that accompanied them. (Part of the money collected from the preaching of the indulgences in Germany secretly went to a powerful archbishop, to pay for an exemption from the rule prohibiting a bishop from holding more than one see at a time.) The higher clergy possessed ostentatious power and wealth, and many orthodox reformers at the time pointed out that it was hard to see the apostolic fishermen in the mighty, often scandalously worldly, prince-bishops. This resentment, like the other reforming impulses of the time, was double-edged, inspiring both genuine reform (Cardinal Ximenz de Cisneros) and naked greed (Henry VIII's seizure of the monasteries).

Perhaps the best way of seeing the medieval Church is by analogy with modern architectural restoration. In l500, the Church was a huge and complex structure with innumerable wings added over the centuries. Reformers, many of them quite orthodox, objected that behind all this it was difficult to discern the holy simplicity of the original Church.

Medieval piety was embodied in an extraordinarily comprehensive and effective system that penetrated every corner of human existence, providing religious meaning for every situation in life, from politics to illness and everything between. But thoughtful believers also wondered if their faith had not become much too formalistic, encouraging almost mechanical attitudes which bordered on, and sometimes crossed into, superstition; which encouraged people to believe that they could put themselves right with God simply by performing certain prescribed acts, without much concern for personal conversion.

Numerous late medieval reformers urged a simpler, more internalized approach to faith. As time went on, some such movements (Thomas a Kempis movement, for example) proved thoroughly Catholic; others metamorphosed into Protestantism. Still others (such as that of Erasmus of Rotterdam) remained ambiguous. By 1500, all thoughtful people understood that there was a need to reform, something which the Fifth Lateran Council of 1517 addressed too little and too late.

But the call for a greater interiority also revealed the second, only half-conscious issue of the day the loss of the sacramental sense, the unease, often the overt hostility, to all outward manifestations of religion, the growing tendency to regard faith as a wholly interior and spiritual thing. At one end was the kind of piety that reveled in the complex network of rituals, images, indulgences, and relics, while at the other end were the spiritualist impulses that would end in movements like Quakerism. The Reformers fell somewhere in between, Luther close to the Catholic sense in some ways, Ulrich Zwingli the first Puritan. (To understand the Reformation it is more important to understand Zwinglian iconoclasm than Lutheran doctrine.)

History shows that orderly change is very difficult to achieve, and the tragedy of the sixteenth century was that valid, indeed imperative, calls for deeper interiorization of religion sometimes led to the wholesale rejection of the sacramental sense itself, epitomized in Zwingli's denial of the Real Presence, on the grounds that the infinite God could not be present in the finite elements of the Eucharist.

The Catholic Reformation, on the one hand, unflinchingly reaffirmed all disputed doctrines and practices. But tacitly it also accepted the legitimacy of some of the reformist criticisms. Attempts were made to counter popular superstitions through catechizing. Serious efforts were made to reform the structures of the Church so that it could be seen primarily as a spiritual entity. Above all, as in the work of St. Ignatius Loyola and the great Spanish mystics, it responded to that thirst for genuine interiority that has been characteristic of believers in every age.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

James Hitchcock. "The Real Issues of the Reformation." Catholic Dossier 7 no. 5 (September-October 2001): 40-41.

This article is reprinted with permission from Catholic Dossier.

The Author

James Hitchcock, historian, author, and lecturer, writes frequently on current events in the Church and in the world. Dr. Hitchcock, a St. Louis native, is professor emeritus of history at St. Louis University (1966-2013). His latest book is History of the Catholic Church: From the Apostolic Age to the Third Millennium (2012, Ignatius). Other books include The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life volume one and two, published by Princeton University Press, and Recovery of the Sacred (1974, 1995), his classic work on liturgy available here. James Hitchcock is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Copyright © 2001 James Hitchcock