A Happy Little Reflection on Hell

- DALE AHLQUIST

The fear of death is universal and quite natural. In fact, Chesterton calls the fear of death common sense, a coarse and pitiless common sense.

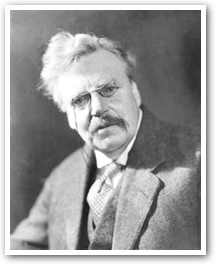

G.K. Chesterton

G.K. Chesterton1874-1936

We all know we are going to die, and we all hate the fact that we are going to die. Because death is something rotten. It is the "failure of the flesh." In fact, Chesterton used the fear of death to make people better appreciate life. That is why when someone said that life was not worth living, Chesterton took out a gun and offered to shoot the person. Suddenly, for some reason, when you're staring down the barrel of a gun, life is worth living! Life is good. Life is precious.

While the fear of death is universal, the fear of damnation is more personal, more individual, because the fear of damnation is the voice of our conscience. It is calling ourselves into judgment. It is the inescapable sense that if we were to get the judgment that we really deserved, it would not be pretty. Justice is something we all want when we feel we have been wronged. But justice is something we really don't like to think about the rest of the time, which is most of the time. Our fear of damnation is really only a deep realization that God is just.

Just as Chesterton used the fear of death to evoke a deeper appreciation of life, he uses the fear of damnation to create a deeper appreciation of salvation. The fear of damnation is usually portrayed as something very negative, but Chesterton does not hesitate to portray it as a very positive thing. In his book on St. Francis of Assisi, he writes:

"A very honest atheist with whom I once debated made use of the expression, 'Men have only been kept in slavery by the fear of hell.' As I pointed out to him, if he had said that men had only been freed from slavery by the fear of hell, he would at least have been referring to an unquestionable historical fact."

It is the fear of hell that freed the slaves. Slaves were not afraid of hell, but slave-owners were. Thomas Jefferson fretted about the fact the newly formed United States of America, founded on freedom, had not freed the slaves. He was worried, he said, "because God is just."

They were preaching to the smug and the self-satisfied, to those who abuse every one of God's gifts, including the gift of language, to create philosophies to rationalize away religion. Chesterton calls these philosophies of "unfathomable softness." They have forgotten God certainly. But their big mistake before that, was that they had forgotten hell.

When you forget hell, it means you have forgotten the larger reality outside of yourself. You have collapsed into egoism and self-centeredness. Hell is separation from God. And just to make it worse, hell is being stuck with only yourself.

Hell, of course, is always portrayed as fire, but when you forget hell, you freeze. (Which is probably why Chesterton compared Scandanavia to hell). Chesterton says, "The place where nothing can happen is hell." You cannot act. Nothing can happen. You are frozen. That is why hell is symbolized by chains, and heaven is symbolized by "wings that are free as the wind."

But ironically, you cannot act in this world, unless there is a hell. You cannot act unless you know that your actions are significant, eternally significant. You cannot act unless there are consequences for your actions, whether they are good or bad.

In other words, without hell, there is no free will.

We were made for heaven, but we are not forced to go there. Chesterton says that it is a fundamental dogma of the Catholic Faith "that all human beings, without any exception whatever, were specially made, were shaped and pointed like shining arrows, for the end of hitting the mark of Beatitude." But the shafts of those arrows, he says "are feathered with free will, and therefore throw the shadow of all the tragic possibilities of free will."

The most tragic of the tragic possibilities is eternal damnation. The Church has always tried to emphasize "the gloriousness of the potential glory," but it also has to "draw attention to the darkness of that potential tragedy."

Chesterton says that another name for free will is moral responsibility, and "Upon this sublime and perilous liberty hang heaven and hell, and all the mysterious drama of the soul."

There is, however, within Christianity, and even within the Catholic Church, a growing and creeping heresy called Universalism, the idea that everyone no matter what will go to heaven. This is clearly contrary to the teaching of the Church, and yet we see in many places an increasing resistance to talk about hell, about the "tragic possibilities" that accompany the glory of free will. The Universalists have done the Protestants one better. The Protestants reduced the scheme of salvation to "faith alone," but the universalists have even dumped faith. Now it's salvation no matter what.

But human dignity depends on the doctrine of free will. Chesterton says that another name for free will is moral responsibility, and "Upon this sublime and perilous liberty hang heaven and hell, and all the mysterious drama of the soul." The drama of the soul is this amazing possibility that "a man can divide himself from God." But even more dramatic is that a man can be reconciled to God. It is not logical – or theological, for that matter – that we can be reconciled with God if we cannot be separated from him.

Hell is not a subject to be avoided; it is a place to be avoided. Not thinking about Hell is a great danger. We might even fool ourselves into thinking there is no Hell. But thinking about Hell is a very good idea. It is a good way to keep ourselves out of it.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Dale Ahlquist. "A Happy Little Reflection on Hell." The Catholic Servant (2011).

Dale Ahlquist. "A Happy Little Reflection on Hell." The Catholic Servant (2011).

Reprinted by permission of the author, Dale Ahlquist.

The Catholic Servant – a tool for evangelization, catechesis and apologetics – is published monthly and distributed free through parishes and paid subscriptions.

The Author

Dale Ahlquist is the President of the American Chesterton Society. He is the author of Knight of the Holy Ghost: A Short History of G.K. Chesterton, The Complete Thinker: The Marvelous Mind of G.K. Chesterton, In Defense of Sanity: The Best Essays of G.K. Chesterton, Common Sense 101: Lessons from G.K. Chesterton, G.K. Chesterton â The Apostle of Common Sense, and is the publisher of Gilbert Magazine, editor of The Annotated Lepanto, and associate editor of the Collected Works of G. K. Chesterton. He has written and lectured on Chesterton so much that he has not bothered getting a real job. He lives near Minneapolis with his wife and six children.

Dale Ahlquist is the President of the American Chesterton Society. He is the author of Knight of the Holy Ghost: A Short History of G.K. Chesterton, The Complete Thinker: The Marvelous Mind of G.K. Chesterton, In Defense of Sanity: The Best Essays of G.K. Chesterton, Common Sense 101: Lessons from G.K. Chesterton, G.K. Chesterton â The Apostle of Common Sense, and is the publisher of Gilbert Magazine, editor of The Annotated Lepanto, and associate editor of the Collected Works of G. K. Chesterton. He has written and lectured on Chesterton so much that he has not bothered getting a real job. He lives near Minneapolis with his wife and six children.