Cheap Sex and the Decline of Marriage

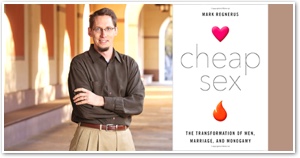

- MARK REGNERUS

Why is marriage in retreat among young Americans?

Kevin, a 24-year-old recent college graduate from Denver, wants to get married someday and is "almost 100% positive" that he will. But not soon, he says, "because I am not done being stupid yet. I still want to go out and have sex with a million girls." He believes that he's figured out how to do that:

Kevin, a 24-year-old recent college graduate from Denver, wants to get married someday and is "almost 100% positive" that he will. But not soon, he says, "because I am not done being stupid yet. I still want to go out and have sex with a million girls." He believes that he's figured out how to do that:

"Girls are easier to mislead than guys just by lying or just not really caring. If you know what girls want, then you know you should not give that to them until the proper time. If you do that strategically, then you can really have anything you want…whether it's a relationship, sex, or whatever. You have the control."

Kevin (not his real name) was one of 100 men and women, from a cross-section of American communities, that my team and I interviewed five years ago as we sought to understand how adults in their 20s and early 30s think about their relationships. He sounds like a jerk. But it's hard to convince him that his strategy won't work — because it has, for him and countless other men.

Marriage in the U.S. is in open retreat. As recently as 2000, married 25- to 34-year-olds outnumbered their never-married peers by a margin of 55% to 34%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. By 2015, the most recent year for which data are available, those estimates had almost reversed, with never-marrieds outnumbering marrieds by 53% to 40%. Young Americans have quickly become wary of marriage.

Many economists and sociologists argue that this flight from marriage is about men's low wages. If they were higher, the argument goes, young men would have the confidence to marry. But recent research doesn't support this view. A May 2017 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research, focusing on regions enriched by the fracking boom, found that increased wages in those places did nothing to boost marriage rates.

Another hypothesis blames the decline of marriage on men's fear of commitment. Maybe they just perceive marriage as a bad deal. But most men, including cads such as Kevin, still expect to marry. They eventually want to fall in love and have children, when their independence becomes less valuable to them. They are waiting longer, however, which is why the median age at marriage for American men has risen steadily and is now approaching 30.

My own research points to a more straightforward and primal explanation for the slowed pace toward marriage: For American men, sex has become rather cheap. As compared to the past, many women today expect little in return for sex, in terms of time, attention, commitment or fidelity. Men, in turn, do not feel compelled to supply these goods as they once did. It is the new sexual norm for Americans, men and women alike, of every age.

This transformation was driven in part by birth control. Its widespread adoption by women in recent decades not only boosted their educational and economic fortunes but also reduced their dependence on men. As the risk of pregnancy radically declined, sex shed many of the social and personal costs that once encouraged women to wait.

These forces have been at work for more than a half-century, since the birth-control pill was invented in 1960, but it seems that our norms and narratives about sexual relationships have finally caught up with the technology. Data collected in 2014 for the "Relationships in America" project — a national survey of over 15,000 adults, ages 18 to 60, that I oversaw for the Austin Institute for the Study of Family and Culture — asked respondents when they first had sex in their current or most recent relationship. After six months of dating? After two? The most common experience — reported by 32% of men under 40 — was having sex with their current partner before the relationship had begun. This is sooner than most women we interviewed would prefer.

The birth-control pill is not the only sexual technology that has altered expectations. Online porn has made sexual experience more widely and easily available too. A laptop never says no, and for many men, virtual women are now genuine competition for real partners. In the same survey, 46% of men (and 16% of women) under 40 reported watching pornography at some point in the past week — and 27% in the past day.

Many young men and women still aspire to marriage as it has long been conventionally understood — faithful, enduring, focused on raising children. But they no longer seem to think that this aspiration requires their discernment, prudence or self-control.

When I asked Kristin, a 29-year-old from Austin, whether men should make sacrifices to get sex, she offered a confusing prescription: "Yes. Sometimes. Not always. I mean, I don't think it should necessarily be given out by women, but I do think it's OK if a woman does just give it out. Just not all the time."

Kristin rightly wants the men whom she dates to treat her well and to respect her interests, but the choices that she and other women have made unwittingly teach the men in their lives that such behavior is noble and nice but not required in order to sleep with them. They are hoping to find good men without supporting the sexual norms that would actually make men better.

For many men, the transition away from a mercenary attitude toward relationships can be difficult. The psychologist and relationship specialist Scott Stanley of the University of Denver sees visible daily sacrifices, such as accepting inconveniences in order to see a woman, as the way that men typically show their developing commitment. It signals the expectation of a future together. Such small instances of self-sacrificing love may sound simple, but they are less likely to develop when past and present relationships are founded on the expectation of cheap sex.

Young people in the U.S. continue to marry, even if later in life, but the number of those who never marry is poised to increase. In a 2015 article in the journal Demography, Steven Ruggles of the University of Minnesota predicted that a third of Americans now in their 20s will never wed, well above the historical norm of just below 10%.

Most young Americans still seek the many personal and social benefits that come from marriage, even as the dynamics of today's mating market conspire against them. It turns out that a world in which it is possible to satisfy our sexual desires much more immediately carries with it a number of unhappy and unintended consequences.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Mark Regnerus. "Cheap Sex and the Decline of Marriage." The Wall Street Journal (September 29, 2017).

Mark Regnerus. "Cheap Sex and the Decline of Marriage." The Wall Street Journal (September 29, 2017).

Reprinted with permission of the author and The Wall Street Journal © 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Author

Mark Regnerus is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. His research is in the areas of sexual behavior, family, marriage, and religion. Mark is the author of over 40 published articles and book chapters, and three books: Premarital Sex in America: How Young Americans Meet, Mate, and Think about Marrying (Oxford, 2011), which describes the norms, behaviors, and mating market realities facing young adults, and Forbidden Fruit: Sex and Religion in the Lives of American Teenagers (Oxford, 2007), which tells the story of how religion does — and does not — shape teenagers' sexual decision-making. His latest book is entitled Cheap Sex and the Transformation of Men, Marriage, and Monogamy (Oxford, 2017), in which he describes the world that has come to be due to influence of technology on sex and sexuality. His work has beenwidely reviewed, including in Slate, the Dallas Morning News, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and The New Yorker, and his research and opinion pieces have been featured in numerous media outlets.

Mark Regnerus is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. His research is in the areas of sexual behavior, family, marriage, and religion. Mark is the author of over 40 published articles and book chapters, and three books: Premarital Sex in America: How Young Americans Meet, Mate, and Think about Marrying (Oxford, 2011), which describes the norms, behaviors, and mating market realities facing young adults, and Forbidden Fruit: Sex and Religion in the Lives of American Teenagers (Oxford, 2007), which tells the story of how religion does — and does not — shape teenagers' sexual decision-making. His latest book is entitled Cheap Sex and the Transformation of Men, Marriage, and Monogamy (Oxford, 2017), in which he describes the world that has come to be due to influence of technology on sex and sexuality. His work has beenwidely reviewed, including in Slate, the Dallas Morning News, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and The New Yorker, and his research and opinion pieces have been featured in numerous media outlets.