No Fathers, No Hope

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

"The inexpressible sadness which emanates from great cities," says Gabriel Marcel in Homo Viator (1952), "a dismal sadness which belongs to everything that is devitalized, everything that represents a self-betrayal of life, appears to me to be bound up in the most intimate fashion with the decay of the family."

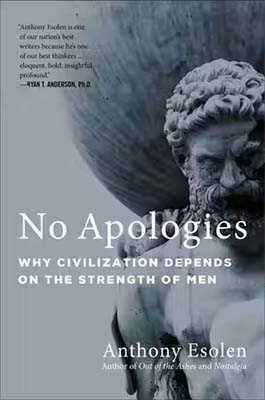

Editor's note: The following is an excerpt from the author's new book, No Apologies, released by Regnery Publishing. Read the original excerpt at Law & Liberty.

❧

Marcel wrote those words before the attack on manhood itself — and therefore on fatherhood — was mounted with an unparalleled and unprecedented hatred of nature. Hope is dyed in the soul's grain. Hope is not a mere calculated guess. There is a chasm that separates the husband and wife who treat the child merely as an object of prudence, an heir to succeed them, to be their substitute, from "those who, in a sort of prodigality of their whole being, sow the seed of life without ulterior motive by radiating the life flame which has permeated them and set them aglow." That chasm may as well be as wide as the universe: consider parents who think of the child as a choice, a lifestyle accessory, or a lapdog in a city apartment.

Why do men work, says the poet Charles Peguy, if not for their children? The father throws himself away in hope, looking forward to the time when he will be no more on earth than a name or a rumor of a name but his children will be alive, and people will say of him — if they remember him at all — that he was a good man but his children are better. He hands on his old tools to his sons, tools shiny with the wear of his hands. He watches his children grow and is proud: he does not want them always to be babies. And when the young children come up to him for a kiss before they go to bed at night, and "they bend their neck laughing like a young, like a beautiful colt, and their neck, and the nape of their neck, and their whole head," the father places his kiss right upon their crown, "the center of their hair, the birth-place, the source, the point of origin of their hair." (This is from The Portal of the Mystery of Hope, published posthumously in French in 1929; Peguy himself died a hero's death in 1914, in the first weeks of the Great War.)

Marcel picks up on this insight from Peguy, that fathers are the "great adventurers of the modern world," accepting the risk of a big family, instead of simply "acquiring life as one puts electricity or central heating into a house." The father, he says, makes a creative vow. He does not say, "I will give only so far." I knew a woman once who told her husband that she would agree to have a second child only on condition that he buy her an expensive sports car. He found the arrangement to his taste. That was, as Marcel says, "incompatible with the inward eagerness of a being who is irresistibly impelled to welcome life with gratitude." No one in our time looks askance at a woman living alone with five cats. Our politics and economics seem aimed at producing old women with cats. And whole great sections of society, formal and informal, public and private, look askance at a happily married woman with five children, who devotes her day to making a lively home for them. A lonely revolution has it been.

"But the woman, not the man," comes the objection, "must bear the new life within her body, and so it is she and not he who must sacrifice her position at work, and something of her ambitions. You cannot make a father of him without making a mother of her." A strange world, wherein motherhood is considered a sacrifice and not a glory. If you argue that motherhood must be accompanied by physical burdens and pain, and perhaps great disappointment, a constriction of your freedom, I must ask what you think your work is for. Your joy? Who finds joy in an office? Prestige? How many people in the world will know your name even if you attain the heights of your profession? How many will know it twenty years after you have died? And what is twenty, to the centuries to come? But to bring into the world an immortal soul — another human life, another being that is more beautiful and more complex than all the physical universe besides — that is a trivial thing?

But there is truly an asymmetry between motherhood and fatherhood, and it suggests to us what intellectual, spiritual, and social power is implied in patriarchy. For the father, as Marcel suggests, must make a vow, a promise that the mother does not have to make, and not because he is more important to the child than she is. Quite the reverse. He is far less important, in any immediate physical way. His fatherhood begins in a kind of nothingness, says Marcel. He contributes the seed, and if we were talking about many of the mammals, his work as far as the specific mother and her offspring are concerned would be finished at that point. The female must bear the brood in her body, must suckle it, must clean it, must tend to it during its time of weakness, until it is grown and can fend for itself.

Human fatherhood is therefore mediated, says Marcel, or rather comes into genuine existence, by means of a creative vow. It is akin to the vow that a human being can make to give up his very life. A mother bear may fight a predator to the death to protect her young. That is in her nature. But there is no promise involved; it is pure instinct. The human father, however, has no such overriding instinct. Sometimes he may even look upon the child as an intruder between him and the woman who is the object of his affection. But he makes a promise, a boundlessly creative one. That promise transcends the moment and the place and the tender feelings he may experience as he looks upon the mother and child.

We traduce our fathers for not being as wise and as good as we demand, but we dare not call ourselves wise and good in turn, and we do not pause to think of what generations hence will call us.

Let me give as an example the account of the birth of Jesus, as we find it in the gospel of Matthew. The evangelist focuses on Joseph. When he learns that his betrothed, Mary, is with child, and he knows that it is not his own, he considers divorcing her — literally setting her aside, because he is a just man, and doing it quietly, because he wishes as little harm as possible to come to Mary. But an angel appears to him in a dream: "Joseph, son of David, do not fear to take Mary your wife, for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Spirit; she will call his name Jesus " — Hebrew Yeshua, meaning The Lord saves, "for he will save the people from their sins" (Matthew 1:20–21). We suppose that Joseph is in a most unusual and uncomfortable position, but it is in essential ways the pattern of fatherhood. We fathers are all like Joseph. We cannot know for certain that a child is ours; see Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale for the near-tragedy of a father who doubts his fatherhood and in a fit of unjust madness accuses his wife of adultery, to condemn her to death. But beyond that, the father's bond with the child can be tenuous. He must not just accept the child, but also incorporate the child into his creative vow, into his self-devotion for the future — quite aside from any feelings he may or may not have for that child.

We see Joseph do just that. The angel appears to him not simply to tell him of the Divine paternity of the child, but to tell him what he, Joseph, must do as the child's father here on Earth. The medieval artists who with a jocularity in their souls portrayed Joseph at the Nativity as an old man off to the side and sleeping, while Mary gazes lovingly into the eyes of the child, captured a deep and abiding truth. Were we dealing with cats or dogs or other beasts that engage in "casual fruition," to use Milton's words, the sire would not be in the picture at all. But there is Joseph, not steeped not in the passion of parental love, but rather in the passion of responsibility. He is dreaming intensely — and learning in those dreams how to protect the mother and child. "Rise," says the angel, when Herod has learned of the newborn king of the Jews, "take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there till I tell you; for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him" (Matthew 2:13). Joseph learns in a later dream that it is time to return to Israel, because Herod is dead (2:20). But when he hears that Herod's son is on the throne, he needs no dream to advise him, but clears out of his family's ancestral village of Bethlehem, and settles to the north in Galilee, in Nazareth.

We may be tempted to consider these dreams as mere devices to convey the child Jesus from one place to another. But the Evangelist does not consider them so. Even before we hear about the conception or the birth of Jesus, we hear what his place is in a vast history of fatherhood: for this is "the book of the genealogy" (Greek geneseos: a new creation, a new genesis) "of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham" (Matthew 1:1). We must think of Joseph along with the fathers of old, and this is not just a matter of blood descent. It involves the whole history of a people, as Matthew is careful to point out: "So all the generations from Abraham to David were fourteen generations, and from David to the deportation to Babylon fourteen generations, and from the deportation to Babylon to the Christ fourteen generations" (1:17). Joseph the son of David must protect Jesus, looking forward to what the child will do, and so the promise extends into the distant future, even, as we learn, to the end of time. To Mary is given the much fuller revelation of Jesus and his person and his mission; from Joseph, rather, is required a vow made in a kind of darkness.

Hence patriarchy is a function of hope. Think of the hopelessness of the secular world, which has set its face in stubborn self-destruction against the figure of the father, and ultimately against the fatherhood of God. Where is the hope? No one believes any longer in the saving power of technological progress; we must have fewer people in the world, not more; we demand the so-called right to kill the unborn child, which is feared as a threat, not longed for as a promise; we demand the so-called right to divorce, which is itself a confession that we have nothing to hope for from marriage, but much to dread; we traduce our fathers for not being as wise and as good as we demand, but we dare not call ourselves wise and good in turn, and we do not pause to think of what generations hence will call us. It is not just a gray life without fathers. It is a severely constricted life, bound to the present, not a culture but a mirthless floating along with the suggestions of mass phenomena. Perhaps we may put it this way: be governed by fathers, or let the tiller go, and the ship float wherever the water takes it. It has no direction: no past, and therefore no future.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." Regnery Publishing (May 2022): pages 105-110.

Anthony Esolen. "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." Regnery Publishing (May 2022): pages 105-110.

Reprinted with permission of Law & Liberty.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2022 Law & Liberty