The Role of Human Sympathy in the Work of Social Justice Part I

- DONALD DEMARCO

There was once a young man whose parents, in an attempt to improve the family's finances, purchased a large house that was to be used as a school for young ladies.

|

Sociologists who believe that their discipline is a science are a distinctly undramatic lot. They believe — religiously, one might say — that black is simply black, and white is nothing other than white. They cannot envision that a man growing up in a dark environment can have a bright future, or that one emerging from a brilliant background can enter into a gray adulthood. Such sociologists know something about social conditioning, but little or nothing about the power of moral virtue and how it can bring drama and optimism into the most sordid and unpromising of lives. They hold the strange belief that it is bad to be monolithic, but wise to be monochromatic. Yet it is at least as narrow and dangerous to be monochromatic as it is to be monolithic. Life is an art whose potentialities are as multiple as the rainbow is colorful.

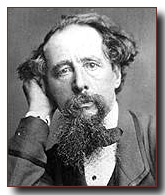

There was once a young man whose parents, in an attempt to improve the family's finances, purchased a large house that was to be used as a school for young ladies. No pupils ever came, however, — not even one. Credit failed. The family's small, well-fingered collection of books was sold. The young man was sent to the pawnbroker with teaspoons, silver teapots, and other small articles that fetched a few shillings. Little by little, the household furniture disappeared, until all that was left was a kitchen table, a few chairs, and the beds. Finally, the father was arrested and placed in debtor's prison.

Our young man, one of eight children born to his improvident and now impecunious parents, was sent to work at a blacking warehouse where he would wrap and label pots of blacking from eight in the morning until eight at night, Monday through Saturday, for six shillings a week. He was barely twelve years old at the time. Living apart from everyone else in his family (and under unbearable conditions), he missed them terribly and visited them in prison every night after work and on Sundays.

He ate bread and milk for breakfast, and his supper consisted of bread and cheese. His lunch was usually stale pastry or a flabby currant pudding. He was not only malnourished, but suffered from painful bouts of colic.

The warehouse itself was a tumble-down building, odorous with dirt and decay. Rats overran its rotted floors and dank cellars. The lad's workmates were coarse and insensitive. They dubbed their out-of-place associate, "the young gentleman". In reflecting on this dark period, much later in life, he lamented that he had "No advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no support, from anyone that I can call to mind," and added that "but for the mercy of God, I might easily have been, for any care that was taken of me, a little robber or a little vagabond."

Although his tenure at the blacking warehouse, that produced paste-blacking for boots and fire-grates, was no more than four or five months, the experience seemed an eternity of despair from which he felt no prospect of ever being released. He tearfully expressed to his father that the sun had set upon him forever. For posterity, he confided: "No words can express the secret agony of my soul."

But the formative lesson he learned during this period was not despair, but something infinitely more positive. In his study of this extraordinary man, Edgar Johnson states that "the blacking warehouse that made him a man of insuperable resolve and deadly determination, also made him for life a sympathizer with all suffering and with all victims of injustice." In another study of the same man, Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie agree that this dark, seemingly hopeless period, "had forged an indissoluble bond of sympathy, even of identity, with the homeless, the friendless, the orphans, the hungry, the uneducated, and even the prisoners of London's lower depths."

|

The

Last of the Great Men

(1812-1870) |

His deprivation was so painful that he was determined to become generous. His alienation was so intolerable that he vowed that he would always be sympathetically united with the marginalized. He became one of the world's most successful social revolutionaries. He definitely destroyed, or at least helped to destroy, certain unjust institutions. And he did so with his pen, merely by describing them. Chesterton could not find a life more paradoxical than his and stated that "If he learnt to whitewash the universe, it was in a blacking factory that he learnt it." Chesterton wrote these words in a book whose title reveals both the identity and the stature of this exceptional human being: Charles Dickens, The Last of the Great Men.

Dickens transmuted the tribulations that impressed themselves so deeply on him when he was young into the immortal characters he created years later. His father became Mr. Micawber, Mr. Pickwick, or Edward Dorrit; his mother, Mrs. Nickleby; his landlady, Mrs. Pipchin; his first love, Dora Spenlow; and himself, David Copperfield, or Oliver Twist.

His sympathy for all human beings allowed him to spark a social-Justice revolution without losing sight of the inherent dignity of each person. On the one hand, all his writing seemed to say "Cure poverty"; on the other hand, they were fully in accord with Christ's beatitude, "Blessed are the poor". He was urging improvement in the social conditions of the working class, but at the same time, he was showing that the Cratchits, despite their poverty, were still happy, and Scrooge, despite his wealth, was the picture of misery. Through his novels he taught that mere pity for the poor is pitiful, but not respectful, and that through loving sympathy, we not only unite ourselves with others but help them improve their life. The truly great man, therefore, is less concerned about his own greatness as he is about the greatness that exists within everyone else. As Chesterton explains, with Charles Dickens in mind, "There is a great man who makes every man feel small. But the real great man is the one who makes every man feel great."

See also, "The Role of Human Sympathy in the Work of Social Justice Part II"

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

DeMarco, Donald. The Role of Human Sympathy in the Work of Social Justice Part I.

Reprinted with permission of Donald DeMarco.

The Author