The Making of a New Benedict

- GEORGE WEIGEL

His parents names were Joseph and Mary (which provoked innumerable jokes in his later life), and he was their third child, following his sister, Maria, born in 1921, and his brother, Georg, born in 1924.

|

“What an exquisite person” — that verbal snapshot of Pope Benedict XVI one week after his election, taken by a senior Vatican official and acute observer of the Catholic scene, would not have surprised many of those who had known Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and dean of the College of Cardinals; or, before that, as Professor Dr. Joseph Ratzinger; or, before that, as Father Joseph Ratzinger. The new pope’s courtesy, humility, and shy friendliness, like his remarkable intelligence, had long been obvious to those who knew him. However true the description, though, to characterize the 265th Bishop of Rome as an “exquisite person” barely scratches the surface of his personality — even if it usefully confounds some of the regnant stereotypes.

Who is he?

It may help to think of Pope Benedict as a man who showed his form early. In 1943, sixteen-year-old Joseph Ratzinger was a conscript member of a German anti-aircraft unit stationed at Obergrashof, near Munich. A “very reserved, fairly inconspicuous figure,” as one of his fellow conscripts remembers him, he didn’t leave much of an impression — except on one occasion. A high-ranking officer, who couldn’t have been anything but intimidating, was inspecting the unit, and the boys were lined up at attention. Each was asked by the officer what he wanted to be as an adult. Several said that they wanted to be pilots; others, presumably, said tank commanders, or engineers, or something else suitably manly, as the Wehrmacht understood manliness. When the inspecting officer came to thin, shy Joseph Ratzinger and asked him what he wanted to be, the response was unexpected: “I would like to become a parish priest.” Many of the others burst out laughing. But as a fellow veteran remembered, “to give such an answer took courage.”

It took that, of course: it took a brave sixteen-year-old to confront a representative of armed totalitarian power — and, perhaps even more threateningly, his fellow teenagers — with a truth they didn’t want to hear. It took more than courage, though. This wartime episode also suggests enormous self-possession, a quiet confidence created by a rock-solid faith. Joseph Ratzinger has never been one to make a spectacle of himself. But he is prepared to defy the conventions when doing so is what the truth requires — even when telling the truth means facing down the stares of his superiors and bearing the taunts of his peers.

It was a trait that would serve him well, and cause him no little pain, in the years after 1943.

![]()

SON OF CATHOLIC BAVARIA

Although he was frequently, and understandably, described as the first “German pope” in a very long time, Joseph Ratzinger is less a German than a Bavarian — if by “German” we mean someone formed by the culture that emerged from the German Reich that Bismarck welded together from several hundred states in the mid-19th century. Ratzinger’s cultural roots run deeper than post-Bismarckian Germany — and, in some important instances, are in tension with the modern state that Bismarck wrought. The 265th Bishop of Rome is a man of the Land Bayern, the product of an intact and thriving Catholic culture from which he drew important lessons about the nature of faith, the Church, and worship. His Bavarian roots also mean that he is the second pope in succession who was formed in the intense Catholic ferment of Mitteleuropa in the first half of the 20th century — a ferment that did not take its intellectual and cultural cues from Berlin and the Prussian approach to life and learning.

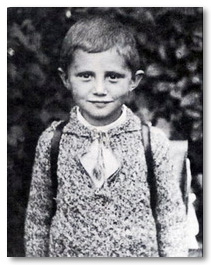

Joseph Ratzinger was born on April 16, 1927, in Marktl am Inn, a village in Upper Bavaria on the north side of the river Inn, which eventually merges into the Danube at Passau; Marktl is a few miles from the Marian shrine of Altötting, a pilgrimage site for Bavarians and Austrians since the Middle Ages. April 16 was Holy Saturday in 1927, and in those days, before Pius XII’s liturgical reform, the Easter Vigil service was celebrated in the morning. Thus Joseph Ratzinger was baptized late on the morning of his birth with newly blessed Easter water, a special privilege on which he would reflect seventy years later:

I have always been filled with thanksgiving for having had my life immersed in this way in the Easter mystery . . . To be sure, it was not Easter Sunday but Holy Saturday, but, the more I reflect on it, the more this seems to be fitting for the nature of our human life: we are still awaiting Easter; we are not yet standing in the full light but are walking toward it full of trust.

His parents’ names were Joseph and Mary (which provoked innumerable jokes in his later life), and he was their third child, following his sister, Maria, born in 1921, and his brother, Georg, born in 1924. Maria would become her cardinal-brother’s longtime housekeeper before her death in 1991. Georg would also be ordained a priest and go on to lead the Regensburg Cathedral Choir for many years, acquiring an international reputation in the process. Music and the intensity of his father’s anti-Nazi views are two of Joseph Ratzinger’s clearest memories from a childhood that was spent, in some respects, on the move.

The elder Joseph Ratzinger was a police constable, or commissioner; his duties and, later, the volatile politics of the period, required him to move his family frequently. Thus, in 1929, the Ratzingers left Marktl for Tittmoning, on the Salzach River (which forms the German-Austrian border). Tittmoning, the future pope would recall, was “my childhood’s land of dreams,” with a great town square surrounded by large houses; decorated shop windows during the Christmas season; an “unforgettable mighty fortress that towers over the town,” at which the Ratzinger children would picnic with their mother; and an old monastic church, decorated in the Baroque style. The childhood idyll didn’t last, however. The elder Joseph Ratzinger’s criticism of the Nazis made life there impossible, so, in 1932, the family moved to Aschau am Inn, a village of farms, where the constable’s family was quartered in a country house whose first floor doubled as police headquarters.

The Ratzingers arrived in Aschau in December 1932; a month later, President Paul Hindenburg named Adolf Hitler Reichschancellor. The future pope carried two indelible memories from the next four years: the brownshirts spying on the local priests and informing on these “enemies of the Reich”; and the mortification of his father, who was, at least formally, working “for a government whose representatives he considered to be criminals.” Young Joseph Ratzinger took his first steps in education at the village school in Aschau.

|

Joseph Ratzinger |

The family peregrinations stopped in 1937, when Joseph Ratzinger Sr. retired from police work (as he was required to do at age sixty) and moved to Traunstein, where he had bought an old farmhouse on the outskirts of the town in 1933. In the Traunstein Gymnasium, or secondary school, the younger Joseph Ratzinger began his studies in Latin, Greek, history, and literature — an education, Cardinal Ratzinger would later recall, which “created a mental attitude that resisted seduction by a totalitarian ideology.” In 1939, the year Hitler set Europe ablaze, Ratzinger, who must have been considering a priestly vocation for some time, entered the minor seminary in Traunstein at the urging of his pastor; his brother, Georg, was already studying there. The young seminarian found it hard to adjust to the rigidities of the study hall after having enjoyed reading on his own at home, but his real problems came on the athletic field; as he later put it, delicately, “I am not at all gifted in sports . . .” It was during this period that Ratzinger had his brief encounter with the Hitler Youth, membership in which was compulsory; a sympathetic teacher got him the certificate of attendance that Ratzinger simply didn’t want to go get himself. “And so,” as he later wrote, “I was able to stay free of it.” (An impertinent reporter, once probing these years in Ratzinger’s adolescence, asked, at a German press conference held to present Cardinal Ratzinger’s autobiography, why there weren’t any references to girlfriends in the book. The legendarily formidable Panzerkardinal replied, with a twinkle in his eye, “I had to keep the manuscript to one hundred pages.”)

At the outbreak of World War II, the Traunstein seminary was designated as a military hospital, so the rector found a new location for the students in a convent school in the countryside outside the city. Happily, from Ratzinger’s point of view, “there was no place for sports,” so for exercise the students hiked, fished, built dams: “It was the kind of happy life boys should have. I came to terms, then, with being in the seminary and experienced a wonderful time in my life. I had to learn how to fit into the group, how to come out of my solitary ways and start building a community with others by giving and receiving.”

It was not to last, however. In 1943, Ratzinger and other Traunstein seminarians were conscripted into the German anti-aircraft corps and sent to the Munich area, where they continued their Gymnasium education in their off-duty hours. Ratzinger found himself in the telecommunications section of the service, and never fired a gun. The Allied invasion of France in June 1944 came to Ratzinger and most of his fellow conscripts “as a sign of hope . . . there was a great trust in the Western powers and a hope that their sense of justice would also help Germany to begin a new and peaceful existence.” At the same time, these teenagers wondered, as well they might, whether they would live to see that day — “None of us could be sure that he would live to return home from this inferno.”

In September 1944, having come of military age, Joseph Ratzinger was assigned to the infantry and, after basic training, was sent to a unit that was digging anti-tank fortifications on the Austrian- Hungarian border. After being reassigned to a post near his Bavarian home, he fell ill, but a sympathetic officer exempted him from military duties. The Third Reich was crumbling, but by late April 1945, the American liberators had still not arrived; so, as Ratzinger later wrote, “I decided to go home.” Deserters were being shot on sight, but Ratzinger was fortunate to have suffered a minor injury, his arm was in a sling, and the two soldiers he encountered on his way home told him to move on. When the Americans finally arrived in Traunstein, they chose the Ratzinger home as headquarters, and young Joseph was easily identified as a soldier. So he “had to put back on the uniform I had already abandoned, had to raise my hands and join the steadily growing throng of war prisoners” who were being lined up in a meadow outside town. The POWs were marched to the military airport at Bad Aibling and then shipped to a large POW camp near Ulm, where fifty thousand were imprisoned. Ratzinger was there for about six weeks and then released; he was trucked to Munich and left on the outskirts of the city, from whence he walked and hitchhiked the 120 kilometers to Traunstein. He arrived on the evening of the Feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and went straight to his home.

“In my whole life I have never again had so magnificent a meal as the simple one that Mother then prepared for me from the vegetables of her own garden.” The family reunion was completed in July, when Georg Ratzinger returned from military service in Italy. On his arrival home, the young musician sat down at the piano and played the hymn Grosser Gott, wir loben dich [Holy God, we praise thy name].

Joseph Ratzinger’s published memoirs are rather more revealing about his family life, struggles, fears, and aspirations than those of other prelates. Those memoirs and other biographical interviews make it clear that his was a close-knit family. Like his predecessor as pope, Ratzinger was deeply influenced by the integrity and sturdy Catholic faith of his father, whose “simple power to convince came out of his inner honesty.” Ratzinger’s love for his mother and her “warm and heartfelt piety,” and for the brother and sister to whom he stayed close throughout his life, are also obvious from his autobiographical reflections.

Yet the more one reads Ratzinger’s recollections of his early life, the more it becomes clear that, for the young Bavarian, the Catholic Church quickly became “home” in a special, even unique, way. In his conversations with the German journalist Peter Seewald, Cardinal Ratzinger spoke about his childhood excitement at receiving his first children’s missal (a book containing the prayers of the Mass, in this case, in simplified form), and then “progressing to a more complete missal, [then] to the complete version. That was a kind of voyage of discovery.” At the same time, he was discovering the wonder of polyphony and other forms of Church music, the beauty of religious art, and the intellectual satisfaction to be had from understanding what all these things meant. Ratzinger never disdained the simple habits of piety he learned as a boy, although his spiritual life obviously deepened over time; yet some of those early habits would remain with him his entire life. Thus, every March 19, on the Solemnity of St. Joseph, the feast of his patron saint, Cardinal Ratzinger would invite other Josephs to celebrate Mass with him or to join him for a day trip and lunch out-side Rome. The earthiness of Bavarian piety — the intertwining of the transcendent and the human — was deep in him. From childhood on, Joseph Ratzinger experienced the Catholic Church as something wonderful, a divinely touched human community to be explored in all its richness, diversity, and complexity.

The war years taught him some important lessons that he would only later bring to intellectual expression. His father’s anti-Nazi convictions and his own experience of the war suggested a truth that the French Jesuit Henri de Lubac had made the theme of his 1943 study, The Drama of Atheistic Humanism : “It is not true, as is sometimes said, that man cannot organize the world without God. What is true is that, without God, he can ultimately only organize it against man. Exclusive humanism is inhuman humanism.” That was a truth about the world. There was also a truth about Christianity to be learned from Germany’s Nazi experience: the more robust and orthodox a community’s faith, the better able it was to resist the siren songs of National Socialism. As his intellectual biographer, Aidan Nichols, put it, Ratzinger would later cite “the collapse of liberal theology before the advance of Nazi ideology . . . as one of the more instructive lessons provided by the history of his homeland.” While the National Socialist regime was obviously one factor in the heresy of the Nazified Deutsche Christen, these “German Christians” were, in another respect, a wretched by-product of the hollowing-out of Christian conviction from within. Ratzinger also learned from the Nazis his first lessons in the mortal danger of measuring human lives by their utility, or lack thereof. He had a cousin, just about his own age, who had Down’s syndrome. When he was fourteen, the regime took his cousin away for what was described as “therapy,” but was, in fact, euthanasia.

Like many Bavarian Catholics, Joseph Ratzinger welcomed the defeat of the Third Reich and the restoration of democracy, the enthusiasm for which he once described as amounting to a kind of “religious fervor” in the post-war years. Ratzinger always remembered, however, that Hitler had come to power by legal means, and that the Nazis’ opportunity had come about because of the fatal flaws of the Weimar Republic, a beautifully constructed democratic system. It takes more than systems, though, to make democracies work; it takes virtues. That was another lesson Joseph Ratzinger learned early.

![]()

PRIEST, PROFESSOR, PERITUS

In November 1945, Joseph Ratzinger and his brother, Georg, entered the major seminary at Freising. (Freising, a town some twenty miles north of Munich, is joined to the much larger city in the name of the local archdiocese, which is “Munich and Freising.” The diocese of Freising dates back to 739, while the double-named archdiocese into which the Freising diocese was incorporated only dates to 1818). In the seminary, which was also serving as a hospital for foreign POWs awaiting repatriation, older war veterans and youngsters like Joseph Ratzinger were united in a determination to serve the Church and, in doing so, to help rebuild a physically and morally shattered Germany. For a mind like Ratzinger’s, the return to academic life was a longawaited feast: “a hunger for knowledge had grown in the years of famine, in the years when we had been delivered up to the Moloch of power, so far from the realm of the spirit.” In addition to the prescribed courses in philosophy and other subjects, Ratzinger and his colleagues “devoured” novels, with Dostoevsky, Claudel, Bernanos, and Mauriac among the favorites. The seminary curriculum didn’t neglect the hard sciences; as Ratzinger would later put it, “we thought that, with the breakthroughs made by Planck, Heisenberg, and Einstein, the sciences were once again on their way to God.” Romano Guardini and Josef Pieper were favorites among the contemporary theologians and philosophers.

|

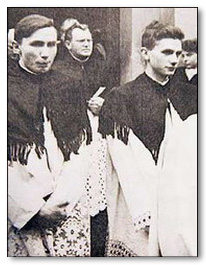

Georg &

Joseph Ratzinger (1945) |

The prefect of Ratzinger’s study hall, Father Alfred Läpple, put him to work reading books that introduced him to Heidegger, Jaspers, Nietzsche, Buber, and Bergson, philosophers most certainly not on any Roman (or American) seminary reading list in those days; the young Ratzinger immediately made an intuitive connection between the personalism of Buber and Jaspers and “the thought of St. Augustine, who in his Confessions had struck me with the power of all his human passion and depth.” Conversely, and concurrently, Ratzinger had an unhappy introduction to the philosophy and theology of Thomas Aquinas, which were presented in what he later termed a “rigid, neo-scholastic” form that was “simply too far afield from my own questions.” The young Bavarian scholar was beginning to range freely across centuries of western and Christian thought, a lifelong process that would eventually give him an encyclopedic knowledge of theology. His seminary experience with neo-scholasticism would also mark him permanently, and would later make him the first non-Thomist in centuries to head the Catholic Church’s principal doctrinal office.

In 1947, Ratzinger went to Munich for his theological studies, encountering there a host of renowned theologians and teachers who were breaking with the rigidities of neo-scholasticism and rethinking Catholic dogmatic theology through a return to the Bible, to the Fathers of the Church in the early centuries of Christianity, and to the liturgy, the Church’s worship, which they believed was a locus theologicus, a “source” of theology. Preeminent among these teachers was Michael Schmaus, who had come to Munich from Münster after the war and was considered a theologian on the cutting edge of the renewal of Catholic thought. Ratzinger was also intrigued by the New Testament scholar Friedrich Wilhelm Maier, and while he could never accept aspects of Maier’s method of biblical interpretation, he learned from him a passion for biblical studies which, as he later put it, “has always remained for me the center of my theology.” Another influential teacher during these years was his Old Testament professor, Friedrich Stummer, who helped the neophyte theologian to understand that “the New Testament is not a different book of a different religion that, for some reason or other, had appropriated the Holy Scriptures of the Jews as a kind of preliminary structure.” No, “the New Testament is nothing other than an interpretation of ‘the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings’ found from or contained in the story of Jesus.” In Munich, under the tutelage of Josef Pascher, Ratzinger began to explore the mid-century liturgical movement more deeply and to read in the mystical theology that had grown out of one center of that movement, the Benedictine monastery at Maria Laach. The Bible and the liturgy came together for Ratzinger, intellectually, in his Munich studies: “Just as I learned to understand the New Testament as being the soul of all theology, so too I came to see the liturgy as its living element, without which it would necessarily shrivel up.”

In short, Joseph Ratzinger completed his initial theological course at a time of great ferment in German theology — a movement of intellectual and spiritual renewal that had begun in the 1920s. It was a movement in search of a theology “that had the courage to ask new questions and a spirituality that was doing away with what was dusty and obsolete and leading to a new joy in the redemption.” At the same time, according to his friend, the German journalist H. J. Fischer, Ratzinger’s introduction to the vitality of Catholic intellectual life convinced him that “that which is Catholic cannot be stupid, and that which is stupid cannot be Catholic.” Pre-conciliar Catholicism, in Ratzinger’s experience, was anything but stale: it was bracing, vital, and intellectually vibrant. At the same time, theology was done as a self-consciously ecclesial discipline, a way of thinking with the Church. Ratzinger’s memoirs of this period conclude with a telling episode:

In 1949 . . . Gottlieb Söhngen [a Catholic theologian] held forth passionately against the possibility of [the definition of the dogma of Mary’s assumption] before the circle for ecumenical dialogue presided over by Archbishop Jäger of Paderborn and Lutheran Bishop Stählin . . . In response, Edmund Schlink, a Lutheran expert on systematic theology from Heidelberg, asked Söhngen point-blank: “But what will you do if the dogma is nevertheless defined? Won’t you then have to turn your back on the Catholic Church?” After reflecting for a moment, Söhngen answered: “If the dogma comes, then I will remember that the Church is wiser than I and that I trust her more than my own erudition.” I think that this small scene says everything about the spirit in which theology was done [in those days] — both critically and with faith.

Joseph and Georg Ratzinger were ordained priests by Cardinal Michael Faulhaber on June 29, 1951, the Solemnity of Sts. Peter and Paul, in the cathedral of Freising. It was a splendid summer day that Ratzinger would always remember as “the high point of my life.” When the Ratzinger brothers came to Traunstein for their first Masses, the town opened itself to them unreservedly; complete strangers invited the brothers into their homes to bestow the first priestly blessing. The point, Ratzinger later insisted, was not himself or his brother: “What could we two young men represent all by ourselves to the many people we were now meeting?” The point was that the people of Traunstein recognized the change in them: “In us they saw persons who had been touched by Christ’s mission and had been empowered to bring his nearness to men.”

After fifteen months of parish work in Munich, Father Joseph Ratzinger was assigned to the Freising seminary as a teacher, with adjunct work with young people and liturgical service at the cathedral. Above all, though, Ratzinger had to finish his doctorate, which he completed in July 1953 with a dissertation on “The People and the House of God in St. Augustine’s Doctrine of the Church.” Father Ratzinger was now Dr. Ratzinger. Before he could reach the highest levels of German scholarship, though, and in order to qualify as a university professor, he had to write a second doctoral dissertation, the Habilitationsschrift , or “habilitation.” And here, for the first time in his academic career, Ratzinger got into serious trouble.

Under the influence of Gottlieb Söhngen, he decided to move from the Fathers to the Middle Ages in his habilitation thesis, and specifically from St. Augustine to St. Bonaventure. In the habilitation, Ratzinger, following Bonaventure, argued that revelation is “an act in which God shows himself”; revelation cannot be reduced to the propositions that result from God’s self-disclosure, as certain forms of neoscholasticism tended to do. Revelation, in other words, has a subjective or personal dimension, in that there is no “revelation” without someone to receive it. As Ratzinger would later put it, “where there is no one to perceive ‘revelation,’ no revelation has occurred, because no veil has been removed.” Gottlieb Söhngen had no problem with this, and, as the first reader of Ratzinger’s habilitation, accepted the thesis enthusiastically. But Michael Schmaus, the second reader, was not merely unpersuaded, he was adamantly opposed, and told Ratzinger in mid-1956 that he was rejecting the thesis — a stunning decision that, if upheld, would have denied Ratzinger the academic career he sought. Schmaus seems to have had serious difficulties with Ratzinger’s conclusions about the nature of revelation. Offended pride may also have taken a hand, as it often does in academic life: the fact that Ratzinger had decided to do a dissertation on a medieval theologian, Bonaventure, under a director other than Schmaus, an acknowledged authority on the Middle Ages, may have had something to do with Schmaus’s rejection. Four decades later, Ratzinger speculated that ecclesiastical politics could have been at work, too, as Schmaus may have heard rumors of modernizing tendencies in Ratzinger’s teaching.

After what can be imagined to have been a stormy meeting of the Munich theology faculty, Schmaus did not prevail entirely: the decision was made to allow Ratzinger to try and revise the thesis. He prudently decided to shift the focus of his habilitation to Bonaventure’s theology of history — a section of the original thesis with which Schmaus had had no problems — and rewrote the entire work in two weeks. It was resubmitted and finally accepted by the faculty in February 1957. Before the habilitation process could be completed, however, Ratzinger had to give a public lecture — with both Söhngen and Schmaus, his two readers, as respondents. The atmosphere at the lecture was electric, and the subsequent discussion turned into a donnybrook between the two respondents. After the polemics were finished, the faculty met again, for what seemed to Ratzinger “a long time.” Finally, the dean emerged from what was likely another stormy session to tell him “without ceremony” that he had passed and now held the habilitation degree. When things settled down, Dr. Hab. Joseph Ratzinger was named a lecturer (the lowest rung on the academic ladder) at the University of Munich. Then, in early January 1958, and “not without some sniper shots from certain disgruntled quarters,” he was appointed a professor of theology at the college of Philosophy and Theology at Freising. Schmaus and Ratzinger were later reconciled and became friends in the 1970s.

|

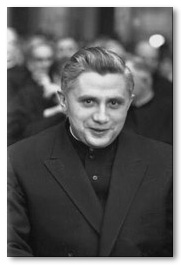

Joseph

Ratzinger (1959) in Bonn |

But Joseph Ratzinger was not to remain in his native Bavaria for long. With his brother’s return from studies to Traunstein, where his assignment included a residence in which the aging Ratzinger parents could live with him, the path was open for the newly accredited theologian to accept an offer to take the chair of fundamental theology at Bonn, an assignment once sought by his mentor Söhngen. He began his work in Bonn on April 15, 1959, the day before his thirty-second birthday, one of the youngest theology professors in Germany and, despite the habilitation struggle, an obviously rising star.

Four months later, however, his father died of a stroke. The family was gathered around the deathbed; afterwards, Ratzinger sensed that “the world was emptier for me and that a portion of my home had been transferred to the other world.” Ratzinger’s mother would die in 1963; her son later paid tribute to his first educators in Christianity by writing that “I know of no more convincing proof for the faith than precisely the pure and unalloyed humanity that the faith allowed to mature in my parents . . .”

Bonn is close to Cologne, and the young theologian soon came into regular contact with the cardinal archbishop of the city, Joseph Frings; Frings had heard Ratzinger lecture on the theology of the impending Second Vatican Council, which had been announced by Pope John XXIII three months before Ratzinger took up his new position. The relationship between the two developed to the point where, when Cardinal Frings left for Vatican II in September 1962, he took the thirty-five-year-old Ratzinger as his theological advisor and arranged to have Ratzinger appointed a peritus, an official theologian, of the Council. During those heady days, Ratzinger worked in tandem with some of the giants of 20th-century Catholic theology, including Henri de Lubac, Jean Daniélou, and his fellow German Karl Rahner. Ratzinger and Rahner had first met in 1956, just when Michael Schmaus was rejecting the younger man’s habilitation thesis.

Ratzinger enthusiastically supported the idea that the Council should begin its work with the reform of the liturgy, for, as he later put it, the Eucharist is “the mystery where the Church, participating in the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, fulfills its innermost mission, the adoration of the true God.” Divine worship, he wrote, is “a matter of life and death” for the Church: “If it is no longer possible to bring the faithful to worship God, and in such a way that they themselves perform this worship, then the Church has failed in its task and can no longer justify its existence.” Yet for all his enthusiasm about the Council’s beginning with the reform of Catholic worship, Ratzinger would later come to the view that the reform as actually carried out was not the reform the Council fathers had intended.

Ratzinger’s almost-aborted work on Bonaventure’s theology of revelation bore fruit in the Council’s seminal Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation [ Dei Verbum ], which took essentially the same view that had gotten him into such trouble: God reveals himself, and that revelation is to be understood as the act in which God encounters human beings, rather than as merely propositions about God. At the same time, it was during his work on revelation at the Council that Ratzinger discovered that he and Karl Rahner, the preeminent German dogmatic theologian and a figure of worldwide influence, “lived on two different theological planets.” They agreed on issues like the reform of the liturgy, methods of biblical interpretation, and other contested questions, “but for entirely different reasons.” According to Ratzinger’s later recollection, Rahner’s “was a speculative and philosophical theology in which Scripture and the Fathers in the end did not play an important role and in which the historical dimension was really of little significance.

For my part, my whole intellectual formation had been shaped by Scripture and the Fathers and profoundly historical thinking.” The dramatic difference between these two theological methods — and the practical results to which it would lead — would have important consequences for the relations between the two men, and indeed for Catholic theology, in the post–Vatican II years.

In Vatican II lore, Joseph Ratzinger is often remembered for having helped draft a speech in which Cardinal Frings denounced the Holy Office for its modus operandi. The methods of the Holy Office, Frings charged in a sensational address in November 1963, “are out of harmony with modern times and are a cause of scandal to the world.” There is little doubt that the charge had substance in those days, but it would be thrown back in Ratzinger’s face more than once in his twenty-three years as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the post-conciliar successor to the Holy Office. Ratzinger, it was frequently charged, had switched sides.

For his part, Ratzinger remembers that his concerns about the Council’s direction — and the dynamics it was setting loose in the Church — began during Vatican II itself. Halfway through the four sessions of Vatican II, the impression was being created that “nothing was now stable in the Church, that everything was open to revision.” An anti-Roman bias, which went far beyond legitimate criticisms of curial stodginess, was in the air — and fouling it. Churchmen and journalists alike were describing the Council as if it were a parliamentary exercise in partisan politics rather than an effort at ecclesial and spiritual discernment. The new Pentecost imagined by John XXIII was being described as, and in some senses had devolved into, a scramble for power. Theologians, tasting power and liking the taste, were imagining themselves as a parallel teaching authority in the Church, a kind of magisterium of experts. None of this, in Ratzinger’s view, had much to do with the kind of reform that he and others had envisioned in the 1950s.

Understanding both Ratzinger’s role at Vatican II and his later criticisms of the Council requires remembering that he was, in fact, a reformer. As Aidan Nichols puts it, Ratzinger agreed with those who thought that the Church of the past few centuries had shrunk itself, theologically and spiritually, and that Vatican II’s task was to “usher Catholics into a larger room.” The reform Ratzinger imagined would have two dimensions, usually described in Council argot by a French term and an Italian term. The reform required ressourcement — a “return to the sources” of Catholic theology in the Bible and in the early Fathers of the Church, where, as Nichols writes, “the Christian religion took on its classic form” from men such as Ignatius of Antioch, Cyprian, Ambrose, Augustine, Leo the Great, Gregory the Great, Athanasius, and John Chrysostom. Ressourcement, it was believed, would free Catholic theology from the cold logic and bloodless propositions of the neoscholastic system; and having been liberated in that way, theology would revitalize Catholic life. That revitalization was the second dimension of the kind of reform Ratzinger imagined: the famous aggiornamento, or “bringing up to date,” of the Church’s practices, structures, and methods of encounter with modern culture and society. Yet here, too, the living Christ had to be at the center of reform, for the “objective” of aggiornamento, Ratzinger wrote immediately after the Council, “is precisely that Christ may become understood.” According to Ratzinger and those of his cast of mind, the biblical and patristic ressourcement would allow the aggiornamento of the Church in the modern world to be a genuine, two-way dialogue, with the Church offering fresh insight to modernity, its aspirations and its discontents. For a truly reformed Church would understand, once again, that it “does not exist for its own sake”; rather, the Church is “the continuing history of God’s relationship with man.”

Ratzinger was right: neo-scholasticism had gone stale, and fresh air was needed in theology and in the Church. The problems came, in Ratzinger’s view, when aggiornamento lost its tether to ressourcement — when the “updating” of the Church did not begin with a return to the sources of Catholic intellectual and spiritual vitality. When ressourcement and aggiornamento came unglued, then Christian belief was simply another opinion, and “believing” meant “having opinions.” Instead of building Nichols’s larger room in the Church, an aggiornamento unmoored from ressourcement stripped the room of a lot of its furniture. And in doing so, misguided forms of aggiornamento were unleasing what a later generation would have called Catholic “deconstruction”: the new question became, “How little can I believe, and how little must I do, to remain a Catholic?” (Or, as Aidan Nichols put it, more elegantly, “Once aggiornamento had parted company from ressourcement, adaptation could degenerate into mere accommodation to habits of mind and behavior in secular culture.”) These were emphatically not the questions proposed by reformers like Joseph Ratzinger, for whom the whole point of the ressourcement was to empower a Catholic updating that put the people of the Church into steady contact with the vast riches of their tradition, which they would gradually make their own in order to serve the world in a distinctive way. Aggiornamento detached from ressourcement, Ratzinger came to see, was stupid. And as he had intuited in his first days as a student of theology, what is stupid cannot be authentically Catholic.

In other words, the real debate in post-conciliar Catholicism would not be between reformers, on the one hand, and ideologically hardened anti-moderns like the French archbishop Marcel Lefebvre (whose followers refused to use the reformed liturgy and thought the Council’s Declaration on Religious Freedom heresy), on the other. Lefebvre’s rejectionism was a sideshow. The real debate was between two tendencies among the reformers: a tendency that held to the crucial linkage of aggiornamento to ressourcement, and a tendency that was, over time, less and less interested in a return to the sources and more and more enthralled with modern culture. Ratzinger’s fidelity to the first tendency would define the next forty years of his service to theology and the Church, as the widening fault line between the two tendencies spilled out from academic life to touch virtually every aspect of Catholic life and practice in the developed world.

![]()

BETWEEN THE COUNCIL AND THE CONGREGATION

Prof. Dr. Hab. Joseph Ratzinger enjoyed teaching at the University of Münster, to which he had moved from Bonn in 1963; years later, he would remember the venerable Westphalian city as a “beautiful and noble” one. 39 Yet he felt the tug of his native Bavaria and the south of Germany, so, when he was invited to take a chair in dogmatic theology at the University of Tübingen in 1966, he accepted. Interestingly enough, it was Hans Küng who pressed for Ratzinger’s appointment within the Tübingen faculty (and reportedly short-circuited the usual procedures to ram it through). Tübingen’s was among the most distinguished theological faculties in Germany, with strong Catholic and Lutheran scholars alike; the chance to be in contact with the latter was, for Ratzinger, one of the attractions of the move to Swabia.

|

Joseph

Ratzinger (1965) University of Regensburg |

Life at Tübingen soon became contentious, though. For all its brilliance, the Catholic theological faculty was “much given to conflict,” as Ratzinger, who didn’t enjoy such goings-on, gently put it years later. But worse was to come. The existentialism that had been the dominant intellectual leitmotif at Tübingen was quickly displaced by various forms of Marxist analysis, which, as Ratzinger remembers, shook the university “to its very foundations.” Marxism was a swindle of biblical faith, in Ratzinger’s view: “. . . [It] took biblical hope as its basis but inverted it by keeping the religious ardor but eliminating God and replacing him with the political activity of man. Hope remains, but the party takes the place of God, and, along with the party a totalitarianism that practices an atheistic sort of adoration ready to sacrifice all humaneness to its false god.” The situation became completely untenable, from Ratzinger’s point of view, in the summer of 1969. Then, the students of the Protestant theologian union circulated a flyer asking, “So what is Jesus’s cross but the expression of a sado-masochistic glorification of pain?” Two of Ratzinger’s Protestant colleagues deplored this blasphemy, to no avail.

The situation among the Catholic students never got “quite so bad,” but “the basic current . . . was the same.” So, the choice was sharply posed, and Ratzinger “knew what was at stake: anyone who wanted to remain a progressive in this context had to give up his integrity.” That he was not prepared to do, so he decamped from Tübingen and settled in late 1969 at the newly established University of Regensburg, where he would remain for the rest of his academic career. His critics later said that Ratzinger had left Tübingen because he couldn’t handle student radicals. From his point of view, it wasn’t the scruffiness of the student left that made things intolerable, but their Marxisante blasphemies. Theology simply couldn’t be done in an atmosphere where basic Christian symbols were objects of loathing. So he left, for the sake of theology.

The Tübingen years did produce one lasting fruit. Hans Küng was responsible for the dogma lectures in the Catholic faculty of theology in 1967, which left Ratzinger free to take up a project he had been thinking about for a decade: a series of lectures for students from all the faculties, titled “Introduction to Christianity.” Those lectures eventually led to the book of that title, which would become an international bestseller and a staple of introductory theology courses throughout the Catholic world. Those with a sense of the divine irony will appreciate the fact that Introduction to Christianity was made possible by Hans Küng teaching the dogma course at Tübingen that year.

Ratzinger was happy at Regensburg, which was now home to his brother and sister as well. Between the Council and the Tübingen experience, the Sixties had been a decade of unremitting conflict for Ratzinger, and he was eager to get back to serious intellectual work. Pope Paul VI appointed Ratzinger to the International Theological Commission in 1969; during its meetings, he deepened his friendship with Henri de Lubac, S.J., and made new friends, including the Chilean theologian Jorge Medina and the French convert Louis Bouyer. These years also saw a ripening of Ratzinger’s collaboration with the great Swiss theologian, Hans Urs von Balthasar, a pyrotechnic genius whose prolific theological, literary, and spiritual writings constitute one of the extraordinary Catholic intellectual achievements of recent centuries.

With these and other colleagues, Ratzinger discussed the widening breach between the two schools of Vatican II theological reformers, and the way to achieve a genuinely Catholic reform of theology and the Church in light of contemporary culture, its problems and its promise. Balthasar’s idea, which drew Ratzinger’s support, was to bring together in a coherent intellectual movement “all those who did not want to do theology on the basis of the pre-set goals of ecclesial politics but who were intent on developing theology rigorously on the basis of its own proper sources and methods” — in brief, aggiornamento deeply rooted in ressourcement . The method Balthasar, Ratzinger, and their colleagues chose to launch this movement was a journal, which they decided to call Communio [Communion].

Those who had seemingly detached aggiornamento from ressourcement had previously founded the journal Concilium [Council], which appeared in the major European languages; they also ran Concilium within rather narrow ideological boundaries, according to a kind of theological party line. As one of the founders of the French edition of Communio later recalled, this was precisely what the Concilium people had rightly resented about pre-conciliar Roman theology — it enforced a party line. Yet here they were doing it themselves, in Concilium, if from the other end of the ideological spectrum. Communio, by contrast, was intended to be genuinely pluralistic, open to all sorts of theological methods and viewpoints, within the common bond of sentire cum ecclesia [thinking with the Church].

Supported by younger German theologians like Karl Lehmann, and with help from Don Luigi Giussani and members of his Communion and Liberation movement, Communio was first launched in Germany and Italy, but its ambitions were larger. Ratzinger described the broad sweep of the project and its internationalism in his memoirs: “Since the crisis in theology had emerged out of a crisis in culture and, indeed, out of a cultural revolution, the journal had to address the cultural domain, too, and had to be edited in collaboration with lay persons of high cultural competence. Since cultures are very different from country to country, the review had to take this into account and have something like a ‘federalist’ character.” Thus, Communio evolved over the years into a federation of allied, language-based journals. Thirty years after its founding, there were independent, federated editions of Communio published in German, Italian, Croatian, French, Flemish, Spanish (in distinct Spanish and Latin American editions), Polish, Portuguese (in distinct Portuguese and Brazilian editions), Slovenian, Hungarian, Czech, and English. Each edition was responsible for its own content; an annual meeting of senior editors helped keep the Communio network focused in parallel directions.

The Concilium/Communio split gave the Catholic Church an important set of new intellectual journals and a potent international network linking younger, older, clerical, and lay scholars. The split was not without costs for Joseph Ratzinger, though. The parting of the ways between Concilium and Communio marked the end of his friendships and collaboration with Hans Küng and Karl Rahner. Moreover, as the Concilium group (which imagined itself the true heir of Vatican II) waned in influence, while Ratzinger rose in the Church hierarchy, he would be the frequent target of a form of ecclesiastical nastiness known as odium theologicum (which needs — and, in fact, has — no translation). It is not unlikely that the caricatures that dogged Ratzinger for twenty-five years (the Panzerkardinal, “God’s Rottweiler”) were at least inspired by members of the Concilium group with ready access to the media, which in Europe as well as North America was usually ready to pit good “progressives” against wicked “conservatives.” These ideological cartoons were, of course, based on political categories that could not begin to parse seriously the real differences between the two estranged groups of reformers. They nevertheless made for great copy (or so it must have seemed to a lot of editors, given the ubiquity of their use).

During his Regensburg years, Joseph Ratzinger attracted impressive students who came to do their doctorates under his direction. Two of the most prominent were Christoph Schönborn, a young Dominican who would later become editor of the Catechism of the Catholic Church and cardinal archbishop of Vienna, and Joseph Fessio, an American Jesuit who would found Ignatius Press, a distinguished publishing house, and lead several important educational initiatives. Ratzinger did not confine his love for teaching to the classroom, however. From 1970 until 1977 he and the Catholic biblical scholar Heinrich Schlier led a week-long course at a country estate near Lake Constance for young people interested in deepening their understanding of the essentials of Catholic faith — a kind of theological and biblical summer camp, in which Ratzinger and Schlier shared the household duties with their students. In launching this initiative, Ratzinger was deliberately patterning himself after Romano Guardini, the great Munich theologian and one of the seminal figures of the Catholic revival in mid-20th-century Mitteleuropa, who had built a similar intellectual and spiritual center for young people in the 1920s and 1930s. Guardini had written extensively about the Church “after modernity,” which he believed had run its course and was out of gas, culturally and spiritually; it is not difficult to imagine Ratzinger and Schlier talking with their summer-school students along similar lines.

Cardinal Julius Döpfner of Munich and Freising died, unexpectedly, on July 24, 1976. Precisely eight months later, on March 24, 1977, the appointment of Joseph Ratzinger as the new archbishop of Bavaria’s major see was announced. The rather lengthy interregnum suggests that there may have been some contention, in Rome and possibly in Germany, over the Munich succession. Ratzinger himself was not, evidently, in the conversation, and his first reaction to the idea of his becoming the new archbishop was that it was a very bad idea indeed:

I did not think it was anything serious when [Archbishop Guido] Del Mestri, the apostolic nuncio, visited me in Regensburg on some pretext. We chatted about insignificant matters, and then finally he pressed a letter into my hand, telling me to read it and think it over at home. It contained my appointment as archbishop of Munich and Freising. I was allowed to consult my confessor on the matter. So I went to Professor Auer, who had a very realistic knowledge of my limitations, both theological and human. I surely expected him to advise me to decline. But to my great surprise he said without much reflection: “You must accept.”

Ratzinger still had his doubts, but, back at the nuncio’s hotel, he wrote his letter of acceptance to Pope Paul VI on a piece of the hotel’s stationery. His ordination as a bishop was celebrated in the Munich cathedral on May 28, 1977, the vigil of Pentecost. Ratzinger chose as his episcopal motto, Cooperatores Veritatis [Co-Workers of the Truth], a reference to 3 John 1.8, which linked his past life as a professor to his new ministry as a teacher-bishop, and which indicated how he thought about the bishop’s and the Church’s role in the late-modern world — the Church and her bishops ought to remind men and women that they are, indeed, capable of grasping the truth and being grasped by the Truth who is God.

Less than a month later, on June 27, 1977, Archbishop Joseph Ratzinger was created a cardinal by Pope Paul VI, along with Giovanni Benelli of Florence, Bernardin Gantin of Benin, Frantisek Tomásek of Prague, and Luigi Ciappi, a curialist, in what was destined to be Paul’s last consistory. Fourteen months after conferring his final red hats, Paul VI died. And Joseph Ratzinger, who had been a university professor in Regensburg a mere sixteen months before, was now called into conclave to help elect the successor of St. Peter.

Given the brevity of the first conclave of 1978, which elected Alibino Luciani of Venice as John Paul I on the fourth ballot, it seems reasonable to assume that Cardinal Ratzinger was part of the Luciani coalition assembled by his cardinalatial classmate Giovanni Benelli. Luciani had gone out of his way to visit Ratzinger when the latter took his first vacation as a cardinal in Luciani’s archdiocese in the summer of 1977; Ratzinger was touched and impressed by the courtesy to so junior a member of the College as he. For the long-term future of the Catholic Church, however, the most important thing that happened to Joseph Ratzinger during the August conclave in 1978 was that he finally had a chance to talk seriously with Karol Wojty l a, the archbishop of Kraków.

Josef Pieper, the German philosopher whom Ratzinger had admired during his student days and who had become a friend, wrote Ratzinger after a 1974 philosophical congress in Italy, urging him to get in touch with Wojty l a, who had made a deep impression on Pieper. Ratzinger and Wojty l a began exchanging books; the Polish cardinal made use of Ratzinger’s Introduction to Christianity in preparing the Lenten retreat he preached for Paul VI and the Curia in 1976, and they met briefly at the Synod of Bishops in 1977. The August 1978 conclave was, however, their first opportunity to speak at length. There was, Ratzinger later recalled, “this spontaneous sympathy between us, and we spoke . . . about what we should do, about the situation of the Church.”

When John Paul I died after a micro-pontificate of thirty-three days, Wojty l a and Ratzinger came once again to Rome to elect a pope — the German from Ecuador, where he had been on a pastoral visit, Ratzinger, like virtually everyone else in the electoral college, was stunned by Papa Luciani’s sudden death:

For me it was a great shock, I have to say . . . we all hoped he could be, on the one hand, a pope of dialogue, very open for all people, with a pastoral capacity, and on the other hand, with a clear theological dimension. So it was really a shock when he died after one month, and for all of us, an examination of conscience: What is God’s will for us at this moment? We were convinced that the election [of Luciani] was made in correspondence with the will of God . . . and if one month after being elected in accordance with the will of God, he died, God had something to say to us . . . we had to reflect on what God’s guidance was at this moment. I think the historical function of John Paul I was to open the door for a non-Italian pope, for a quite different decision.

No one knows Joseph Ratzinger’s position during the early phase of the October 1978 conclave, which eventually deadlocked between the two leading Italian candidates — Benelli, the pope-maker of August, and Cardinal Giuseppe Siri of Genoa, who had been thought papabile in three previous conclaves dating back to 1958. But when the shock of John Paul I’s death and the Benelli/Siri deadlock “created the possibility of doing something new,” as Ratzinger later put it, there can be little doubt that the archbishop of Munich and Freising was one of those enthusiastically supporting the previously unimaginable candidacy of the archbishop of Kraków.

As Ratzinger recalled it, their friendship deepened in the first months of John Paul II’s pontificate, and quickly led to a job offer:

He [John Paul II] often invited me to come to Rome for discussions and from the beginning of the pontificate there was a permanent relationship. When the apostolic palace was under restoration and he was [living] in the Torre Giovanni, I was with him. In 1979 he said, “We’ll have to have you in Rome.” And I said, “You’ll have to give me some time, its impossible now.” His first intention was to make me prefect of the Congregation for Catholic Education but I said, “It’s impossible after only two years to abandon Munich,” so he named Cardinal [William] Baum [then the archbishop of Washington, D.C.] and that was a very good decision. But when a second prefecture was free, I could not resist this a second time.

The “second prefecture” was, of course, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) — successor to the Holy Office and, as reporters never ceased to remind the public, an institution “formerly known as the Inquisition.”

![]()

THE PREFECT

During his lengthy pontificate, Pope John Paul II was served by many outstanding churchmen, some of whom had very large personalities. None of them gave up more for John Paul II than Joseph Ratzinger, the man who couldn’t say “No” twice — particularly when the second request to serve came after the attempt on John Paul’s life in May 1981. Three times, Ratzinger tried to resign — in 1991, 1996, and 2001. Each time, John Paul asked him to stay, and he stayed. The man whom the crowds proclaimed “John Paul the Great” on April 8, 2005, simply could not imagine being pope without Joseph Ratzinger as his principal doctrinal advisor.

What did Ratzinger give up? To the eyes of the world (and to some of his critics), very little: he was one of the two or three most powerful men in the Catholic Church; he could travel the world; he was at the center of Vatican affairs, and not simply on matters involving his congregation. Ratzinger saw things differently. To leave Munich-Freising for Rome in 1981 meant abandoning any hope of writing his theological master work. As he put it to Peter Seewald, “For me, the cost was that I couldn’t do full time what I had envisaged for myself, namely, really contributing my thinking and speaking to the great intellectual conversation of our time, by developing an opus of my own.” Coming to CDF meant spending the bulk of his time on “the little and various things that pertain to factual conflicts and events.” It also meant giving up the scholar-bishop’s luxury of seizing intellectual opportunities; as Ratzinger put it, “I had to free myself from the idea that I absolutely have to write or read this or that.” His primary responsibilities were at his desk on the second floor of the Palazzo Sant’Ufficio, the Palace of the Holy Office (as CDF’s headquarters is still known).

Ratzinger did not propose to give up his intellectual work entirely, a position with which John Paul II was naturally sympathetic. Having determined that previous prefects of the congregation had published theological works in their own names, the two men agreed that Ratzinger could do the same. And, in fact, his personal productivity during the CDF years was striking: some twenty books, largely composed of essays he had written during the CDF years, were published in English while Joseph Ratzinger was prefect. Add to that the volume of documents and studies CDF produced, plus the Catechism of the Catholic Church (for which Ratzinger had oversight responsibility), and the record is remarkable. Ratzinger never did get to write his theological magnum opus, and, now, never will. But there is no disputing the fact that he remained very much a partner in what he called “the great intellectual conversation of our time.” That is why, in 1992, he was inducted into the Académie Française, founded by Cardinal Richelieu in 1635; Ratzinger took the seat previously held by the late Russian physicist and human rights activist Andrei Sakharov.

The Pope and the Prefect

For those willing to look beyond caricatures and immediate controversies, Ratzinger’s appointment as prefect of CDF disclosed several things about John Paul II’s thinking on the state of Catholic theology and its importance in the Church. The first was that John Paul II took theology very seriously indeed. Rather than appointing an experienced Church bureaucrat to head the congregation, John Paul chose a man whom everyone, including his critics, regarded as a scholar of the first rank, one of the finest Catholic theological minds of the 20th century. The appointment also suggested that the Pope, far from wanting to drive theology back into the lecture hall, wanted it to engage the world — but in a distinctively theological way. Thus he chose Ratzinger, who had come to embody an updating of the Church based on a return to the sources of Catholic spiritual and intellectual vitality. And in the third place, the appointment underscored John Paul’s commitment to a legitimate pluralism of methods in theology. Joseph Ratzinger was the first head of the Vatican’s doctrinal office in centuries who did not take Thomas Aquinas as his theological lodestar. Both the Pope and his new prefect respected Thomas and Thomists. They also wanted a wide-ranging theological conversation to shape papal teaching.

|

Cardinal

Joseph Ratzinger & Pope John Paul II |

By both men’s accounts, they worked very well together. In addition to his weekly meeting with John Paul II on Friday evenings, where the two would review the work of CDF, Ratzinger was a regular part of John Paul’s Tuesday lunches, which the Pope used as a sounding board for his general audience addresses — the theology of the body, and the lengthy papal catecheses on the Trinity, the Church, and Mary, were first thrashed out around the dining-room table in the papal apartment, with Ratzinger an active part of the conversation. Their working lunches were also important in shaping major teaching documents, including the encyclical on moral theology, Veritatis Splendor, which Ratzinger once described as “the most theologically elaborated text of the pontificate.”

One aspect of Ratzinger’s interaction with John Paul II bordered on the ironic: even as Ratzinger was the regular butt of animus from the self-styled “progressive” party in Catholic intellectual and leadership circles, those same critics (whose credulity was striking) also believed (and told the equally credulous press) that it was Ratzinger who was keeping the wild man John Paul II from acting on some of his more peculiar notions. One notorious report had it that John Paul was prepared to declare that the Virgin Mary was present in the consecrated bread and wine of the Eucharist until Ratzinger talked him out of it. The “good Ratzinger” was also said to have prevented John Paul on several occasions from declaring this or that to be infallibly taught.

Ratzinger, who once laughed aloud at the “good Ratzinger/bad Ratzinger” characterization had a different recollection of his discussions with John Paul II about how certain things should be done. It was widely reported, for example, that John Paul had wanted to invoke his papal authority to define infallibly the three principal teachings of the 1995 encyclical, Evangelium Vitae [The Gospel of Life] — that the direct and voluntary killing of the innocent, abortion, and euthanasia are always gravely immoral — and that Ratzinger somehow prevented this. The prefect denied that this is what had happened, and described the kind of consultations that had in fact taken place.

During the preliminary discussions leading up to the preparation of the encyclical, John Paul was “interested to have the suggestions of our congregation about what [was] possible,” Ratzinger said. While Evangelium Vitae was being drafted, “the Holy Father was waiting for our response as to what was the [best] way to think about these problems; there was never an opposition, because the Holy Father wanted to be informed about the precise possibilities.” Ratzinger understood that the Pope “wanted to give a very strong formulation” to the three teachings in question; the Pope “was always open to CDF’s suggestions [about] how this should be done.” Through this process of consultation, it was decided that the best way to underscore the seriousness of what was being taught would be to footnote each declaration of grave immorality in Evangelium Vitae with a reference to paragraph 25 of Lumen Gentium, Vatican II’s Dogmatic Constitution on the Church — where the Council had confirmed the infallibility of the “ordinary, universal magisterium” of the world’s bishops in communion with the Bishop of Rome. The universality of the Church’s teaching on these three questions, in other words, was the guarantee that these teachings were true, certain, and unchangeable. John Paul and Ratzinger had agreed that this was the way of formulating Evangelium Vitae that was “most corresponding to the tradition of the Church.”

The Pope’s confidence in his prefect of CDF extended beyond a willingness to engage Ratzinger in conversation about numerous theological and doctrinal matters, including questions of the nature and exercise of John Paul’s own papal authority. The Pope wanted Ratzinger involved in many other aspects of the Church’s governance as well. Thus, at the time of John Paul II’s death, Ratzinger was a member of five Vatican congregations (Oriental Churches, Divine Worship, Bishops, Evangelization of Peoples, and Catholic Education), one pontifical council (Christian Unity), and two pontifical commissions (for Latin America and for the reconciliation of the Lefebvrist schismatics); he was also a member of the advisory council of the Second Section of the Secretariat of State — the Vatican “foreign ministry.” In addition to ensuring, by these appointments, that Ratzinger’s would be a regular presence in the most important deliberations of the most crucial offices in the Vatican, John Paul II honored his prefect as opportunities to do so became available, naming him to the highest rank of cardinal, “cardinal bishop,” in 1993, and giving him the most important title a cardinal can receive — titular bishop of Ostia — in 2002, after his fellow cardinal bishops elected Ratzinger as dean of the College of Cardinals.

The Lightning Rod

The standard trope about the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith — “formerly known as the Inquisition” — tends to obscure the fact that, in the 1988 apostolic constitution, Pastor Bonus [The Good Shepherd], CDF was charged with the positive task of promoting theology in the Church as well as safeguarding the purity of Catholic doctrine. During Joseph Ratzinger’s tenure as prefect of CDF, the congregation met that responsibility of promoting the development of theology through a number of important documents, preeminent among which was the 1990 Instruction on the Ecclesial Vocation of the Theologian.

Theology, the Instruction insists, is “something indispensable for the Church,” and is “all the more important” in “times of great spiritual and cultural change.” Theology has its own proper task — “to understand the meaning of revelation” — and so theology begins with revelation and is always accountable to revelation. At the same time, philosophy, history, and the other human sciences are crucial dialogue partners for theology. Theology must therefore be in conversation with culture: the theologian’s task “is . . . to draw from the surrounding culture those elements which allow him better to illumine one or other aspect of the mysteries of faith.” That is not an easy business and, as the instruction puts it, it is “an arduous task that has its risks.” But the dialogue with culture “is legitimate in itself and should be encouraged.”

Theology is also a distinctive intellectual enterprise in another way, the Instruction proposes. Doing theology as the Church understands it requires the theologian to “deepen his own life of faith” and make prayer an integral part of his or her work. Theology is not only done at one’s desk, or in the library; theology is also done on one’s knees, or in the chapel.

|

Cardinal

Joseph Ratzinger |

For all its intellectual importance, however, theology is an ecclesial discipline, according to the Instruction : if theology is theology and not religious studies, it has a necessary connection to the Church. And it is the Church’s pastors, not the Church’s intellectuals, who are ultimately responsible for maintaining the integrity of Catholic faith. The Church’s teaching authority, or magisterium, lives in a collaborative relationship with the Church’s theologians. But the bottom line, doctrinally, is defined by the magisterium of the Church’s bishops in union with the Bishop of Rome. This relationship requires a communion of faith and charity between bishops and theologians. If serious problems occur, a theologian has not simply the right, but the responsibility, to make known to the authorities of the Church what he or she understands to be the difficulties of the teaching in question; theologians, if they are acting in good faith and with charity, should not mount media campaigns to bring pressure to bear on the Church’s pastors. The Instruction also reminds theologians that every doctrine of the Church is not somehow up for grabs unless it is infallibly defined; that the conversation between theology and the Church’s teaching authority cannot be modeled on political protest; and that the truth of faith is not measured by opinion polls.

In a cultural climate in which theologians are frequently tempted to think of their primary audience as the academy, the Instruction reminds theology that it exists in and for the Church — for strengthening the faith of the people who are the Church and for making the Church’s proclamation of the Gospel more credible in the world. In that important sense, Cardinal Ratzinger was calling theology to a genuine reform — to look beyond its own academic bastions to a wider world of conversation, and to cultures in need of conversion. Thus, the Instruction on the Ecclesial Vocation of the Theologian reflected Ratzinger’s long-held conviction that updating the Church — aggiornamento — must always be grounded in an intellectual and spiritual deepening of the theologian’s appreciation for the riches of the Catholic tradition — ressourcement. The greatness of John Paul II’s thinking, Ratzinger once observed, was that it began from the understanding “that Christianity is not an Idealism, outside of concrete historical reality,” but rather a matter of “creating community, creating solidarity.” Theology, like the rest of the Church, should learn from John Paul “the very different but very real power of truth in history.” The power of theology did not lie in its capacity to shape internal Church politics; the power of theology lay in its capacity, through the Church, to change history, to humanize the world. That was the kind of theology Joseph Ratzinger tried to promote through his work as prefect of CDF.

Yet there is, necessarily, the other side of CDF’s work: its role as guardian of doctrinal integrity. That role, also spelled out in Pastor Bonus, made it inevitable that, under an energetic prefect like Ratzinger, CDF would become the last curial stop for many of the hot-button issues in the Church, including reviewing the work of theologians who may have strayed beyond the boundaries of orthodoxy, and disciplining them as necessary. That CDF could exercise this role, as a matter of last resort, was part of its canonical mandate; that it became the court of last resort was, on several occasions, due in part to the pusillanimous behavior of local bishops or religious superiors, unwilling to weather the controversy and take the criticism that inevitably follows when the Church disciplines anyone.

CDF’s role, and the perception of its role, were also influenced by something new in post–Vatican II Catholic life: a phenomenon that might be called “virtual schism.” Shortly after the Second Vatican Council, the English Catholic priest and theologian Charles Davis, editor of the British publication Clergy Review, left the Catholic Church, claiming that Pope Paul VI had been “dishonest” in describing the Catholic debate on contraception prior to the encyclical Humanae Vitae. It was an honorable move on Davis’s part, given his deep disagreement with the teaching authority of the Church; it also cost him his media audience. For while Charles Davis, dissident Catholic priest and theologian, was an interesting story (of the “man bites dog” sort), Charles Davis, non-Catholic theologian criticizing Rome (“dog bites man”), was not. Charles Davis’s disappearance from the media radar screen after his abandonment of the Catholic Church was a lesson not lost on Catholic theologians of similar views. To stay in play, a theologian had to remain, formally, in communion with the Church, even if he or she was, de facto, in a kind of personal, intellectual, or psychological state of schism. There were, of course, many other reasons, including deep conviction, why Catholic theologians who believed the Church was simply wrong about certain matters decided not to leave, but to stay and fight. It would be a mistake, however, to think that this new phenomenon of virtual schism, shaped as it was by the lessons learned from the Charles Davis affair, did not significantly shape the complex situation that CDF faced under Joseph Ratzinger’s leadership.

Inevitably, Ratzinger and CDF became the lightning rod for charges that John Paul II was running an “authoritarian” Church and “crushing dissent.” The fact that, by the end of John Paul’s pontificate, his critics, including prominent theological dissenters, remained in firm control of many theological faculties throughout the world suggested, to those willing to look, that if this was authoritarianism, it was authoritarianism of a most inefficient sort. (So did the fact that, throughout the pontificate, stores within fifty yards of St. Peter’s Square and one hundred yards of the “repressive” CDF were full of books and magazines by prominent dissidents, dissenting from, indeed attacking, the magisterium of John Paul II.) But perhaps a brief review of some of the crucial cases Ratzinger faced as prefect of CDF will suggest an alternative view — that John Paul’s was not an authoritarian pontificate at all, but rather a pontificate determined to defend authoritative Catholic teaching, in the firm conviction that that was important for both the Church and the world.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

George Weigel. "The Making of a New Benedict." Excerpted from chapter 5 in God's Choice: Pope Benedict XVI and the Future of the Catholic Church (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), 157-187.

The foregoing is excerpted from God's Choice by George Weigel with permission from HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced without written permission from HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022.

More info on God's Choice here:

The Author

George Weigel is a Distinguished Senior Fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C. He is author of The Fragility of Order: Catholic Reflections on Turbulent Times; Lessons in Hope: My Unexpected Life with St. John Paul II; Evangelical Catholicism: Deep Reform in the 21st-Century Catholic Church; Witness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul II; Roman Pilgrimage: The Station Churches; Evangelical Catholicism; The End and the Beginning: John Paul II—The Victory of Freedom, the Last Years, the Legacy; God's Choice: Pope Benedict XVI and the Future of the Catholic Church; Letters to a Young Catholic: The Art of Mentoring; The Courage to Be Catholic: Crisis, Reform, and the Future of the Church; and The Truth of Catholicism: Ten Controversies Explored.

George Weigel is a Distinguished Senior Fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C. He is author of The Fragility of Order: Catholic Reflections on Turbulent Times; Lessons in Hope: My Unexpected Life with St. John Paul II; Evangelical Catholicism: Deep Reform in the 21st-Century Catholic Church; Witness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul II; Roman Pilgrimage: The Station Churches; Evangelical Catholicism; The End and the Beginning: John Paul II—The Victory of Freedom, the Last Years, the Legacy; God's Choice: Pope Benedict XVI and the Future of the Catholic Church; Letters to a Young Catholic: The Art of Mentoring; The Courage to Be Catholic: Crisis, Reform, and the Future of the Church; and The Truth of Catholicism: Ten Controversies Explored.