Soldier for Liberty

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

The two men shook hands, then chose their pistols from a case.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

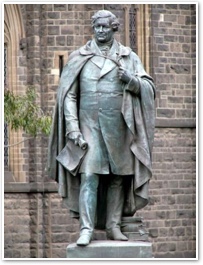

Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell 1775-1847

"Are you certain, Mr. O'Connell," said the first man, with a trace of a sneer, "that you wish to die today? Have you not a wife and a brood of Irish children? Would it not be better to live in disgrace?"

"If I die, Mr. D'Esterre," said Daniel O'Connell, "I die for my countrymen's rights. If you die, you die for a pack of rogues and scoundrels. Much good may it do you."

D'Esterre had won many a duel in the past. He was used to this sort of thing. His puppeteers in the Dublin Corporation, an organization of English bigots whom O'Connell had offended by calling them what they were, looked upon this as their day of liberation from a dangerous pest.

O'Connell had been a reluctant soldier for England during her conflicts with revolutionary France. He said once that if you wanted to build a nation, human blood was a poor mortar for the job. Yet he knew that he could not back down now. It would bring his whole movement into disrepute, and that would be more likely to pitch Ireland into civil insurrection.

"Twenty paces, gentlemen, then shoot," said the referee.

The bullet struck D'Esterre in the stomach. The wound was mortal. It was the first and only time that Daniel O'Connell shed a man's blood for the Irish people. He carried the guilt of it to his grave, bestowing a handsome yearly sum to D'Esterre's widow; and O'Connell was never a wealthy man.

Dueling, O'Connell would write, was "a violation, plain and palpable, of the divine law." He would be challenged again and often, but showed his moral courage in refusing, and in taking upon his shoulders the contempt of his inferiors in grace and probity.

A Penny a Month

O'Connell was arguably the single greatest political organizer in the 19th century. His duel with D'Esterre made him more appalled than ever by violent action, so he determined to compel England by argument and by political strength to grant to the Irish the same rights she granted to Scotsmen and Englishmen.

It was a long and arduous battle. In 1823, eight years after the duel, O'Connell founded the Catholic Association, which quickly grew to prodigious numbers. That was because O'Connell wanted every Catholic Irishman in it. The fee for membership was a mere penny a month — a shilling a year. That brought into the political light the poorest of men, the Irish tenant farmers, in the years before the potato blight. Within a year or two, O'Connell was holding what he called "monster" meetings of the association: as many as 100,000 people would gather in one place to hear the speeches of men who wanted to set them free.

He carried the guilt of it to his grave, bestowing a handsome yearly sum to D'Esterre's widow; and O'Connell was never a wealthy man.

It is important to note that the English wanted to retain their unjust hold over the Irish, but also that they worshiped the same God as the Irish, though not in the same church. In other words, they had consciences after all. O'Connell was counting on the power of moral persuasion, while carrying in his pocket the ace of trumps, which would have been a threat not to wage war, but to cease to prevent the Irish people from it. The English authorities were held in a pincers. They tried to use legalistic means to shut down the association, but O'Connell merely founded another. If they took up arms against the Irish, they would have had a disaster on their hands, certainly a costly distraction from their more lucrative imperial enterprises elsewhere. If they did anything to O'Connell personally, the Irish would not have forgiven them.

We get a sense of what a formidable opponent O'Connell was from this finale of an oration in the House of Commons, late in his life, in 1836. Said O'Connell, "You may raise the vulgar cry of 'Irishman and Papist' against me, you may send out men called ministers of God to slander and calumniate me; they may assume whatever garb they please, but the question comes into this narrow compass. I demand, I respectfully insist: on equal justice for Ireland, on the same principle by which it has been administered to Scotland and England. I will not take less. Refuse me that if you can."

Orange Peel

Much can be accomplished by men who enter into a dynamic enmity with someone they consider a worthy opponent. Daniel O'Connell had one such in Sir Robert Peel, the governor of Ireland and later the leader of the Tory party in the English parliament. O'Connell, jesting on the color boasted by the Protestants in Ireland, called him "Orange Peel," but it was Peel, the enemy, who gave O'Connell critical concessions in the years between 1828 and 1830. O'Connell had been elected a member of Parliament in 1828, but could not take the oath of office, being a Roman Catholic. Everyone knew this. Peel also knew that O'Connell had the backing of six million Irishmen. Something had to be done.

Hence Peel turned about and supported repeal of the longstanding British laws that had kept Irishmen in subjection, and O'Connell took his seat in 1830, without having to submit to the oath. Daniel O'Connell, not Abraham Lincoln, was first known as the Great Emancipator. Peel would later on join with members of the Whigs to repeal tariffs on grain, to help bring food to Ireland during the famine. It was too little and too late, and it cost him the leadership of his party, but Orange Peel was in that battle more of a man than a partisan.

O'Connell was counting on the power of moral persuasion, while carrying in his pocket the ace of trumps, which would have been a threat not to wage war, but to cease to prevent the Irish people from it.

I should not give the impression that Peel eventually saw things as O'Connell did. No sooner did O'Connell take his seat in Parliament than he became the de facto ruler of Catholic Ireland, and pressed for "Repeal" — the repeal of the act that unified Ireland with England, Wales, and Scotland. The Irish wanted to govern themselves, while yet recognizing the monarch of England as the head of state, an arrangement such as would hold in Canada later on. Peel would not give in. Nor would O'Connell. Once again he led a mass movement of the Irish, but this time Peel outlawed their meetings, and in 1844 the now elderly O'Connell was thrown into prison. He appealed to the House of Lords and won his release, but his health was ruined.

Accounts of his death are deeply moving. He felt he was dying, and desired to make a pilgrimage to Rome. It was not to be; the disease of the brain that he had been suffering was irreversible. For his last two days, he could not eat, and he would not take even enough water to wet his tongue, but the name of Jesus was ever on his lips, and he would talk of the Faith and nothing else. The eighty-eight-year-old Cardinal Archbishop of Genoa himself came with his priests to give O'Connell Viaticum and the last rites. All of Genoa prayed for the great man.

He died on the 15th of May, 1847. His heart was embalmed and placed in a silver chalice, to be entombed in Rome, in the Church of Saint Agatha, but his body is buried in the land of his fathers. Wrote his physician: "The heart of O'Connell at Rome, his body in Ireland, and his soul in heaven: is that not what the justice of man and the mercy of God demand? Adieu! adieu!"

A Man for the Ages

O'Connell was a man of straightforward piety, a determined patriot, and a loyal son of the Church. In our time, cultural amnesia is the rule, but O'Connell's reputation went round the world. His young son Morgan, at the age of fifteen, fought in the army of Simon Bolivar, for the deliverance of another man's nation from rule from abroad. Stephen A. Douglas once sneered at Lincoln for allowing his wife to ride in a carriage with Frederick Douglass, but O'Connell met the former slave and became his good friend. Douglass looked up to O'Connell as a hero and an inspiration for his own efforts.

We may get a sense of what Douglass, the novelists Thackeray and Balzac, and countless others admired so deeply by listening to O'Connell addressing his fellow Irishmen on the accession of a Whig government in London. "There is but one magic in politics, and that is to be always right. Repealers of Ireland, let us be always right; let us honestly and sincerely test the Union in the hands of a friendly administration, and, placing no impediments in their way, let us give them a clear stage and all possible favor, to work the Union machinery for the benefit of old Ireland." He was as canny as any Machiavelli could wish, but his principle was the opposite of that put forth by the cynical Florentine. O'Connell triumphed in the right, while trimmers were caught in the tangles of their own cunning.

Dear God, may we see his like again someday — even if we are not worthy of it.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "Soldier for Liberty." Magnificat (March, 2018).

Anthony Esolen. "Soldier for Liberty." Magnificat (March, 2018).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2018 Magnificat