Lent and its Discontents

- MATTHEW LICKONA

When I was confirmed at age fifteen, I took St. John the Baptist as my confirmation saint. A voice crying out in the wilderness, I thought, full of adolescent pride. By Lent of 2003 I was a little older and a little more humble if only as a result of years of sin and failure to do much crying out...

|

To me, Thomas Aquinas College was a spiritual greenhouse, a place where religious flora, imported from all sorts of environs, could flourish in a protective Catholic atmosphere. There, I encountered practices, beliefs, and traditions that had withered away in the more arid, post-Vatican II climes of my upbringing. Some never lost the whiff of antiquity the veneration of saints' relics, for example but others, such as Eucharistic Adoration, took firm root in my soul. Small wonder that my thoughts often drift back to those years; they bear something of the character of a conversion. In that place, I had found new zeal for the faith.

When Lent of freshman year arrived, I was ready to turn that zeal toward self-denial. I had always taken Lent seriously enough to be frustrated with my fellow public-school Catholics when they left school on Ash Wednesday just to get out of school, indifferent to the smudged black cross they received on their forehead while at Mass. But I had never really denied myself for Christ's sake. Most years, I gave up candy, but I certainly didn't love candy enough to really miss it. This year, I would partake of a true fast. My friend Francis and I went on a bread and oatmeal diet four slices of Orowheat Honey Wheat Berry bread for breakfast, four slices for lunch, and a bowl of oatmeal for dinner. Only water to drink. At midnight on Saturday, as the "little Easter" of Sunday began, we would call the local Domino's Pizza. Francis, a man of enormous stature and appetite, once put away two large pizzas during our celebratory binge. I was stuffed after one.

Those who discussed their chosen penances and a bunch of us did fell into three groups. Some were purists who didn't take Sundays off. My group called them rigorists and told them to count the days from Ash Wednesday to Easter. The only way to get the traditional forty days of Lent was by leaving Sundays out. Others started their Sunday celebration after the Vigil Mass late Saturday afternoon, giving them all Saturday night to indulge. They argued that if the Vigil Mass fulfilled your Sunday Mass obligation, then Sunday was underway, liturgically speaking. Wasn't Lent over after the Vigil on Holy Saturday? I couldn't bring myself to join them, but I had no real argument to offer. I, after all, allowed myself St. Patrick's Day to celebrate, along with the Solemnity of St. Joseph and the Feast of the Annunciation. According to one of the school's more traditional souls, I was right in thinking that penance was not to be observed during the latter two feasts, but St. Paddy's was my own invention.

Starting sophomore year, I gave up alcohol. By then, it was something I loved enough to miss. I also tried an early-morning regimen of push-ups, sit-ups, and jogging alongside the highway that led to campus, a hilly, winding, mile-long circuit. This was splendid penance. I detested exercise outside of athletic games, gagged on the sulfuric smell from a nearby mountain as it mixed with the hot exhaust of passing cars, and faltered daily on the uphill return to campus. A pulled hamstring during a soccer game put an end to my suffering. I was grateful to be hobbled.

![]()

Those attempts at mortification were not useless; they were honest efforts toward letting my faith have an impact on my daily life. But while the flesh was willing, the spirit was weak. Mine were feats of endurance, not charity. It showed in the way I talked about them with friends, not exactly flaunting them in public to show my holiness, but still eager for my intimates to know my struggles. "Gosh, this Lent thing is tough, no?" I was gutting it out, sucking it up, struggling toward the relief of Easter, when I would offer Christ my sacrifice-scrubbed soul.

| As I jogged along, gasping for wind, I repeated to myself, "What will you do for Christ, who has done all things for you?" I wanted to give something back, namely, the cramp in my side and the ache in my legs. |

My spirit was (is) Pelagian. Among other things, Pelagius argued that the first move in the romance between God and man was man's to make. Sophomore year, I read as St. Augustine carefully dismantled Pelagius's claim that man's will can avail him anything without the grace of God. I read, as if for the first time, Paul's rhetorical question, "What have you that you did not receive?" (1 Corinthians 4:7). Life is a gift. Redemption is a gift. Faith is a gift. As I jogged along, gasping for wind, I repeated to myself, "What will you do for Christ, who has done all things for you?" I wanted to give something back, namely, the cramp in my side and the ache in my legs. But if Christ had done all, what could I do? The question of grace and free will is a thorny one, but I know my own case. I know that in times of suffering, self-imposed or otherwise, I look first to myself. God is the backup, to be called upon when I find myself insufficient.

Lent 1999 showed the folly of that notion. Ash Wednesday came and went amid a morass of work-related troubles. I write for the San Diego Reader, a weekly newspaper. It's a great job, and I get to work at home and set my own schedule. But for many of my stories, I don't get paid until I actually turn something in, and it takes a measure of self-discipline to keep self-imposed deadlines from sliding further down the calendar. I was up against it.

I told myself I would get to Lent when I got out of the swamp. I had intended to take up daily spiritual reading from the Liturgy of the Hours, but wasn't sure how it was done. The book had more of those multicoloured ribbons to lead you from place to place, and I didn't know how to use them. I gave up TV as a sort of stopgap measure until I found someone to teach me.

The swamp thickened, and when my parents flew out from New York to visit for a week, a black mood settled over me. I was touchy, frustrated, and sulky-thoroughly unpleasant company. My mother gently reminded me of St. John of the Cross's exhortation: "One prayer of thanksgiving when things go badly is worth a thousand when things go well." She encouraged me to praise the Lord at all times. I responded with impatience, even anger. Why was it hard to hear a suggestion from a parent whose love was unquestioned, a suggestion that I seek help from the surest source? Why did I hold on to my suffering, trying to grit my teeth and pull myself out?

![]()

Pride, pride of a masculine sort. Before daily prayer was a true habit for my father, my mother could always tell when he hadn't prayed. He was grouchy and irritable. He didn't handle the frequently intense stress of his work nearly as well. The same was true for my brother. By Easter 1999, Mark was a father twice over, with a master's degree in theology and a burning desire to break into the movie business. Meanwhile, he was trying to swallow his frustration with his job teaching Catholic high school. If he didn't pray, he said, he had a hard time swallowing.

Now it was my turn. "It's important for men to pray," said Mom. "To submit themselves to Christ." Everyone must bend his or her will, but this desire to clean up one's own spiritual mess seems a more masculine failing. From a distance, the danger is easy to see: "It's my problem, I'll deal with it," leading to, "It's my soul, I'll sanctify it." No, you won't.

The problem is maintaining enough distance to keep that in mind. While in college, I read about a vision St. Jerome had of the child Jesus. Jesus asked Jerome why he hadn't given Him everything. Jerome was mystified. "Lord," he protested, "I have devoted my life to your service. I have given you all my works, all my love, all my praise, everything." "No," Jesus replied, "You haven't given me your sins." Give it over, offer it up. Be clay. Submit.

![]()

I have assented to this thought for some time, but I have not managed to send it over the gap between intellect and will. When I was confirmed at age fifteen, I took St. John the Baptist as my confirmation saint. "A voice crying out in the wilderness," I thought, full of adolescent pride. I would preach to my generation, lead them back to the faith they had never really known. By Lent of 2003, a little older and a little more humble if only as a result of years of sin and failure to do much crying out I found myself dwelling more on another of the Baptist's lines: "He must increase, but I must decrease" (John 3:30).

I began to dread the inevitable question from the priest at the holy season's end: "Have you drawn closer to Christ these past forty days?" Has He increased; have you decreased? Do you think of His supreme sacrifice every time you find yourself thirsting for a self-denied Manhattan cocktail? Have you even been able to explain to your curious son why it is good to give things up for Lent? These are not decreasing times. Not only is man often seen as the measure of all things, each individual man often sees himself as the measure of all things. The very existence of the magisterium implies that people need to be taught and formed, and yet the pope and the teaching church are ignored on this, that, and the other as a matter of course. I try to be obedient, but even so, I am hardly free of my inflated self. When Hamlet declares, "What a piece of work is man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties; in form and moving, how express and admirable; in action, how like an angel; in apprehension, how like a god!" (William Shakespeare, "Hamlet," in The Riverside Shakespeare [Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1974], 2.2.1350-53, p. 1156), I am tempted to nod in recognition, or at least to claim that I am basically a good person. But Hamlet knew better: "I am myself indifferent honest, but yet I could accuse me of such things that it were better my mother had not borne me. I am very proud, revengeful, ambitious, with more offenses at my beck than I have thoughts to put them in, imagination to give them shape, or time to act them in" (ibid., 3.1.1777-1781, p. 1161). The trouble is that I do not have eyes to see these offenses. I cannot imagine saying with the psalmist, "My sin is ever before me" (Psalm 51:3). What sin?

![]()

| From a distance, the danger is easy to see: "It's my problem, I'll deal with it," leading to, "It's my soul, I'll sanctify it." No, you won't. |

Pick one, Matthew, pick an easy one say, complaining and try to give it up. Try to control your tongue (to say nothing of your other members). Your first reaction may be to dismiss complaint as hardly any sin at all. Granted, it is not mortal. But is it not pride? Does it not spring from the supposition that you are due better than what you have received, you who have been given life and redemption by no merit of your own? Is it not ingratitude? Are you not grumbling after your fleshpots even as you are fed manna from heaven? Complaint is common currency, the stuff of small talk: "Let me tell you about my day..." It's a mouse of a sin, nibbling at the edges of the soul not as serious as speaking ill of others, or snapping at someone. Very well, should it not therefore be easier to avoid? So go ahead; try to stop it. You say you do it without thinking, that you're barely even conscious of it? That just means it's habitual, practically second nature, and therefore that much harder to root out.

So I started concentrating on avoiding the near occasion of complaint. I started catching myself just after complaining, wincing at the twinge of guilt. Then I started catching myself before complaining, which meant I started feeling good about my success. I grew complacent, lost vigilance, and started backsliding. After a while, I got tired of the effort. Surely I was blowing this out of proportion, expending way too much effort on such a minor offense. Why obsess about complaining? Why obsess about sin?

I know there is danger in dwelling overmuch on man's wretchedness. Paul says, "where sin increased, grace increased all the more" (Romans 5:20). Shouldn't I focus on grace, on gratitude and love? Perhaps. I know that the grace of Christ will have to be the ultimate cause of my decreasing; I haven't forgotten my Augustine. But it helps to keep in mind those aspects of the self which must decrease if He is to increase. It helps to remember that I am a sinner, that "if we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us" (1 John 1:8). It is so easy to forget.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

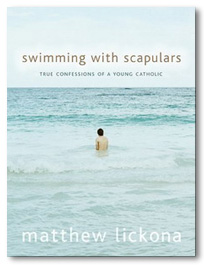

Matthew Lickona. "Lent and its Discontents." In Swimming With Scapulars: True Confessions Of A Young Catholic (Chicago: Loyola Press, 2005): 71-80.

Reprinted with permission of Loyola Press and the author, Matthew Lickona. All rights reserved. To order copies of this book, call 1-800-621-1008 or visit www.loyolabooks.org.

The Author

Matthew Lickona is a staff writer and sometime cartoonist for the San Diego Reader, a weekly newspaper. Born and raised in upstate New York, he attended Thomas Aquinas College in California. He lives in La Mesa, California, with his wife Deirdre and their four children.

|

Swimming

With Scapulars: True Confessions Of A Young Catholic may be purchased here.

Book Description: Dave Eggers meets G. K. Chesterton in this funny, wise,

and acutely perceptive memoir by a precocious young Catholic. For a wine connoisseur

and fan of Nine Inch Nails, 30-year-old Matthew Lickona lives an unusual inner

life. He is a Catholic of a decidedly traditional bent.