A dear, wise, constant friend

- LORD CONRAD BLACK

Lord Conrad Black, former proprietor of the National Post, remembers his friendship of many years with Emmett Cardinal Carter, who died Sunday, April 6 at the age of 91.

|

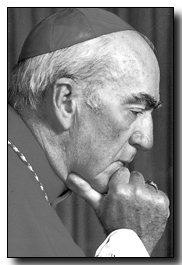

Emmett

Cardinal Carter

Reprinted with permission of The Catholic Register |

'You lost your brother [last year] and you're about to lose another brother." With these selfless words, Emmett Cardinal Carter began our last conversation, in his suite in the Cardinal Carter Wing of St. Michael's Hospital a few weeks before he died. He was by then terribly frail but completely sensible and of firm voice.

We conversed easily for half an hour, as we had more than a thousand times before over the last 25 years. He was, as always, well-informed and we ranged over many subjects, from Iraq to our company. He had done us the unique honour of becoming a director of Argus Corporation when he retired as archbishop of Toronto and remained so to the end.

Finally there came the moment I had dreaded for years, but which I could not dodge or defer, to say goodbye. I managed the hope that I could call on him again when next in Toronto, as I always did. But I had to tell him that his friendship was one of the great joys and privileges of my life and that no one had ever had a dearer, wiser, more constant friend than he.

His sage response was very affecting. I asked him the state of his morale. "Excellent," he said. He felt no fear and had no significant regrets, was thankful for the great life he had had but already somewhat detached from it.

I asked if he was curious about what lay before him. "Yes, I am very curious. Given my occupation, it would be astonishing if it were otherwise."

When the news of his death arrived, by now so long expected but so hard to accept, I thought of our conversations of 20 years ago, often enhanced by considerable quantities of his very good claret, that led to my becoming a co-religionist of his. I told him then, under questioning, that I was satisfied that miracles sometimes occurred and that therefore, logically, any miracle could occur, even scientifically improbable ones like the virgin birth and the physical ascension of Christ. He replied that if our conversations were going to lead to a clear conclusion, I had to believe in one specific miracle.

"If the Resurrection did not occur," said the Cardinal, "all Christianity is a fraud and a trumpery." Already in his 70s, he had bet his life on that proposition. He acknowledged it cheerfully, unshakeable in his faith, but making no effort to exterminate doubt.

Whether in the most informal discussion or on great public occasions, he always knew when to be flexible, when humorous, when unyielding. Even in the winter of his days, labouring under the effects of his stroke in 1980, he was never inept or inarticulate.

And he had an effortless sense of humour. When he stayed with my family and me in the opulent community of Palm Beach, Fla., I asked him on a particularly agreeable afternoon, overlooking the ocean, if this was anything like his vision of heaven. Without hesitation he replied: "If you substitute angels for helicopters, it might be an approximation."

When my associates and I were the subjects of a spurious securities investigation in 1982, I mentioned to Cardinal Carter that we had discovered illegal intercepts on our office telephones, presumably from the Crown Law Office. I wondered if the next initiative from that quarter would be a search warrant on my house, though I accepted that perhaps I was becoming paranoid, since I had done nothing wrong. My concern was that they would seize personal correspondence and records having nothing to do with what they were supposedly investigating, and leak material to the press, behaviour for which there was some precedent. The Cardinal reminded me that "Even paranoids have enemies," and invited me to leave anything personal I might be concerned about at his house. "I doubt that even the most zealous headline-seeker would try to search your house, but if they try that on me, we can flee together!" (No such warrant was, in fact, sought).

Perhaps the most comical session I had with him was when he had me to dinner with the delightfully gregarious Australian novelist Morris West. As we moved determinedly into the digestifs, there began an exchange of recitations from memory of more or less apposite quotations, more theatrically rendered as their authenticity declined.

What he could not foresee, he endured. Toronto had little of the problems of other large Church jurisdictions over sex-related clerical misconduct, largely because he moved early and discreetly to screen and treat potential concerns. His dignified and successful struggle with the effects of his stroke was an inspiration to everyone, though he acknowledged he had difficulty with the Pope's exhortation to "rejoice" at this providential challenge. Almost his entire address at his birthday party on turning 90 was, "Old age is not for weaklings."

The agnostic or anti-clerical elements of the Toronto press alleged that he spent too much time hob-nobbing with the wealthy, like Lytton Strachey's description of Cardinal Manning in Eminent Victorians. His working life was given over almost entirely to the disadvantaged and he vastly increased the scale of charitable and pastoral work in his archdiocese. His social life was no one's concern but his own.

And in fact, his friends were very diverse. When I was in the midst of a financial crisis in 1986, I asked him, if it turned out badly, if that would affect our relations. "Of course not. The only thing I can think of that could, would be if you imagined that material things are even relevant to our relations."

Cardinal Carter's favourite single literary sentence was the end of the introduction of Cardinal Newman's Second Spring. It is: "We mourn for the blossoms of May because they are to wither, but we know withal that May shall have its revenge upon November, in the revolution of that solemn circle that never stops and that teaches us, in our height of hope ever to be sober, and in our depth of desolation, never to despair."

In the 25 years I knew him, his judgment and personality were always sober but never solemn; and never, not at his most beleaguered and not on the verge of death, did he show a trace of despair. He was intellectual but practical, spiritual but not sanctimonious or utopian, proud but never arrogant. He must have had faults, but I never detected any. He was a great man, yet the salt of the earth.

On the day Emmett Carter died, another close friend, who had sometimes acted as legal counsel to the Cardinal, sent me a message ending: "May his spirit soar and may you meet again." Those prayerful hopes were much in my thoughts at his funeral on Thursday.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Conrad Black, "A dear, wise, constant friend." National Post, (Canada) 12 April, 2003.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post.

The Author

Conrad Moffat Black, Baron Black of Crossharbour, PC(Can.), OC, KCSG (born 25 August 1944, Montreal, Quebec) is a historian, columnist and publisher who was for a time the third biggest newspaper magnate in the world. Conrad Black is the author of The Fight of My Life, The Invincible Quest: The Life of Richard Milhous Nixon, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Champion of Freedom, A Life in Progress, and Render Unto Caesar: The Life And Legacy Of Maurice Duplessis.

Conrad Moffat Black, Baron Black of Crossharbour, PC(Can.), OC, KCSG (born 25 August 1944, Montreal, Quebec) is a historian, columnist and publisher who was for a time the third biggest newspaper magnate in the world. Conrad Black is the author of The Fight of My Life, The Invincible Quest: The Life of Richard Milhous Nixon, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Champion of Freedom, A Life in Progress, and Render Unto Caesar: The Life And Legacy Of Maurice Duplessis.