The Heavens Declare the Glory of God: The Story of Joseph Haydn

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

"You're the prince of music," said one fellow to another, as they took their ease in their native German tongue.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

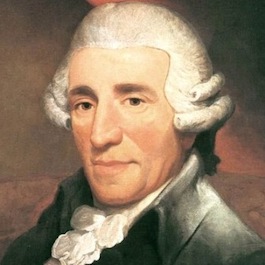

Franz Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn1732 -1809

The chatter of the crowds below floated up to them in the night. The place was Bath, where people came to take the waters for their health, but mainly to enjoy the high life of the English spa. "They love you more than they have loved anyone since our brilliant countryman, Handel." "That is kind of you, Wilhelm," said his friend, a man in his late middle age. "Handel shall be my master." He had heard the Messiah for the first time, in England.

His friend Wilhelm Herschel himself had been a composer of some fame, but he gave it over for study in another kind of order, another counterpoint. He turned some dials to work a telescope atop his house. It was forty feet long. He had built it himself.

"Look here, Joseph," he said, and the old man bent over to peer through the eyepiece.

"What do you see?"

"I see a disk of light. A star?"

"A world like ours, beyond Saturn, revolving about the sun."

"Gott im Himmel! What is its name?"

"I call it Georgium sidus, after our glorious king." That was George III. "An English king with German blood."

"Precisely."

Let there be light

Joseph Haydn left England in 1795 and settled in Vienna, but he kept in mind that meeting with the astronomer. Three years later, he burst forth with his most famous oratorio, The Creation, a musical and theological meditation on the first chapter of Genesis. When I first heard Haydn's interpretation of the verse, "And God said, Let there be light, and there was — Light!" — with its movement from a C minor adagio to a sudden, overwhelming C major chord on that word Light, sung out by the whole choral ensemble — I shivered, and knew why Haydn's German audience erupted into applause when they heard it at its debut.

Haydn's life was not always exemplary. He married badly, and his wife took a lover. He followed her lead some years later. In those days, in the "enlightened" salons and palaces of Europe, you could do that and not be scorned, so long as you weren't scandalous about it. But he never gave up his Catholic faith, and later in life he was chaste. He prayed the rosary before he sat down to compose, and he signed his manuscripts by giving honor to God. I've seen one of the signatures: Laus Deo et B. V. Ma. et om. s.tis: "Praise be to God, and to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and to all the saints."

In 1808, when he was weak with age, the Viennese gave a concert in his honor, featuring The Creation. The singers came to the word Light, and the people applauded, but Haydn from his chair bowed and pointed above, to remind them that true light comes from God alone. The old man's head swam whenever he sat at the piano, but he was still filled with musical ideas, struggling to get free. "I'm nothing but a living clavier," he said, sadly. He was more, of course. He'd become the embodiment of all that was best and most honorable in high culture. A few days before Haydn's death, Napoleon and his armies were shelling Vienna, and when some of the shells exploded nearby, Haydn cried out from the window to the frightened people. He told them not to worry, because where Haydn was, no harm would come to them. But the terror shook his constitution. Still, Napoleon was no barbarian. After he took the city, one of his officers came to Haydn's house to sing for him — from The Creation.

Creation nearly stifled

People nicknamed him "Papa Haydn," though he and his wife were childless. Yet he should have been a father. There was always something mirthful about him: listen to his "Surprise" symphony and try not to laugh while the musicians are playing their beautiful jests! Haydn's childhood might have been very happy, had he had no talent. His father and mother, devout Catholics, noticed early on that Joseph was a brilliant little boy. Herr Haydn couldn't read music, but he did play Austrian folk songs on the fiddle and the harp, and one day he noticed Joseph sawing away with one wooden stick upon another, in perfect time. The boy's treble, too, was pure and beautiful and right on pitch. A kinsman who heard him singing took him to Vienna to study. Of him, Haydn later said, "He gave me more slaps than gingerbread." He was six years old, and he never lived with his parents again.

What did Haydn do for the symphony? He created it. Modern chamber music? The same.

At eight, we find him in a Viennese school, Saint Stephen's. You may have heard of the Vienna Boys' Choir — it is the choir of that school. It had a high reputation in Haydn's time too, but the master, Karl Georg Reuter, was a severe man, whose sole interest in the boy was his voice. He gave him no lessons in composition. Food was sparing, and that may be why Joseph remained small of stature, and why his voice did not drop until he was eighteen. One day Joseph had stayed indoors while the other boys were outside having a lovely snowball fight. His mind was lost in music. Frau Reuter had been going to the door to give the knife-sharpener a pair of shears, when Joseph cried, "Something's burning in the kitchen!" It was the last meager portion of goulash in the house. The lady left the shears on the table, and Joseph picked them up idly, snipping with them to hear the ring and the rhythm of the steel. When the boys came back in, rosy with exercise and fun, Joseph sneaked up behind another boy and, snip! Off went the lad's pigtail. That occasioned a boy-wrestling match, when Reuter came in.

"You must be punished," he said, reaching for his cane.

"There's no need for that," said Joseph. "I'm leaving!"

"Not till you are caned first," said the master.

Joseph did leave, and were it not for his genius, his tremendous energy, and his ability to work hard and long hours — twelve to fourteen a day, when he was a boy, on his own — we would never have heard of him. He said, years later, that he had to be original to survive. He had no one to imitate. So he created.

It's remarkable to consider how close we often came to having not Haydn, but darkness.

Good friend and honest man

What did Haydn do for the symphony? He created it. Modern chamber music? The same. His fame went round the world. In 1815, people in Boston, most of whom had never seen him, in the days before recording, founded the Handel-Haydn Society, which exists to this day. It was impossible to think of culture without music — without musicians in every town and city who could make the compositions real. It might then go to your head, to be so famous, but that doesn't seem to have happened to Haydn. He acknowledged his debts to others — to Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach for one, the great son of a composer greater still. And he attracted others by his warmth and enthusiasm. Beethoven was one of his pupils, and Mozart, much his younger, was his close friend. He wrote to the elder Mozart, assuring him of his son's genius: "Before God and as an honest man I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me either in person or by name; he has taste, and, furthermore, the most profound knowledge of composition."

The plain-spoken Mozart esteemed Haydn just as highly. One evening Mozart was present while one of Haydn's works was being performed, and a man in the audience could do nothing but complain.

"I wouldn't have done that," said the man.

"Nor I," said Mozart. "That's because neither you nor I could have thought of something so perfectly fitting."

Mozart once dedicated six quartets to Haydn, calling them his "six sons," and begging Haydn to treat them kindly, as a father. Haydn did better than that. When Mozart died, Haydn worked hard to establish his friend's reputation in England, where he was still unappreciated. He was "much my superior," said Haydn, and he added that if the world really knew how great Mozart's genius was, the nations would fight one another to claim for their own so precious a jewel. Then he wrote to Mozart's widow and offered to train up their two small sons in music. He kept that promise.

The joy of faith

"Hin ist alle meine Kraft," wrote the elderly Haydn, setting the words to a simple air, "alt und schwach bin ich" — "Gone is all my strength; I am old and frail." But there was nothing morose about him, at heart. Asked about the liveliness of The Creation, Haydn said he could not think of God other than as a being of boundless might and goodness. Such goodness, he said, filled him with such joy, he "could have written even a Miserere in tempo allegro."

"I defy any Christian," wrote a critic and a friend of Haydn, "who has heard on Easter day a Gloria of this composer, to leave the church without feeling his heart expand with sacred joy." Perhaps someday we too may have that experience!

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: Doves in the Clefts of the Rock." Magnificat (September, 2020).

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: Doves in the Clefts of the Rock." Magnificat (September, 2020).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2020 Magnificat