Why Graham Greene's novels will stand the test of time

- FRANCIS PHILLIPS

Greene understood the human condition in a way that secular novelists cannot.

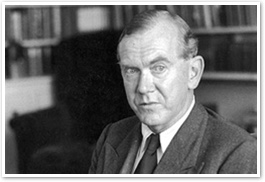

Graham Greene

Graham Greene1904-1991

Wednesday evening I watched Storyville, a BBC programme about two elderly men, one German and the other Austrian: Niklas Frank and Horst von Wechter. Frank is the son of Hans Frank, the notorious Nazi Governor General of Poland and Wechter the son of Otto von Wechter, the Nazi Governor of Galicia.

Their fathers were both guilty of crimes against humanity on an unimaginable scale and the programme showed how their sons were burdened by their legacy. While Frank fully acknowledges his father's responsibility, Horst von Wechter has been desperate to absolve his from complicity in mass slaughter. As always, a programme such as this brings one face to face with the mystery of those who choose to do evil — a choice which lay at the heart of the Third Reich.

"Evil" is a theological concept. In a society that has largely rejected Christianity, it is an uncomfortable word. Can people really be this wicked? And if so, why and how have they become so? Historians, evolutionary biologists and psychologists agonise over the question. Yet it was a word that made entire sense to one of the greatest novelists of the 20th century, Graham Greene, 1904-1991, who died 25 years ago this Sunday. Indeed, the critic VS Pritchett thought Greene's great achievement was his revival of the sense of evil in the English novel.

Greene, raised in the Anglican Church (which he later characterised as "foggy") took instruction upon becoming engaged to a devout Catholic convert, Vivien Dayrell-Browning, and became a Catholic in 1926. His unhappy schooldays at Berkhamsted School, where his father was headmaster, had convinced him of hell and his newfound faith helped him begin "to have a dim conception of the appalling mysteries of love moving through a ravaged world."

For Greene, both in imagination and reality, it was obvious that the world was a fallen one; his own heart, with its lifelong betrayals of those he loved, had taught him that. "I have known so intimately the way the demon works in my imagination", he once commented. What Catholicism gave him was a theological explanation for hell and thus the logic of its opposite — heaven.

Belief in heaven and hell, an acute awareness of mortal sin, the possibility of divine forgiveness in Confession, as well as "the… appalling… strangeness of the mercy of God" (the elderly priest's carefully chosen words to Rose, girlfriend of the gangster, Pinkie, during her Confession at the end of Brighton Rock) are intrinsic to Greene's finest novels: Brighton Rock (1938), The Power and the Glory (1940), The Heart of the Matter (1948) and The End of the Affair (1951).

They show how the novelist, informed by the metaphysical architecture of the Church, exercised his gifts of imaginative intensity and restless intellect on the all too human weaknesses and vices of his characters. The whisky priest in The Power and the Glory, whose love for his illegitimate child teaches him painfully the real (rather than the public) meaning of self-sacrificial love, is one of Greene's most powerful creations.

His realisation of his own sinfulness gives him a poignant glimpse of the possibility of sanctity just before his execution: he "was not at the moment afraid of damnation… He felt only an immense disappointment because he had to go to God empty-handed... It seemed to him, at that moment, that it would have been quite easy to have been a saint. It would only have needed a little self-restraint and a little courage... He knew now that at the end there was only one thing that counted — to be a saint."

Indeed, the critic VS Pritchett thought Greene's great achievement was his revival of the sense of evil in the English novel.

Biographer and journalist Simon Heffer, in a view widely held, thinks that Greene's religion was "a pose… which he turned into a series of money-making opportunities". To a disbelieving world this is an obvious conclusion. But Greene himself was deeply exercised by the theological questions raised by the moral dilemmas of his characters. As Edward Short, literary critic and biographer of Cardinal Newman, wrote in Adventures in the Book Pages, his faith "was central to his being, both as a man and as an author."

Those like Heffer who look askance at Greene's rackety life and judge him either a cynic or a hypocrite, would not understand the sincerity behind his confession in an interview: "I've broken the rules. They are rules I respect, so I haven't been to Communion for nearly 30 years... In my private life, my situation is not regular. If I went to Communion, I would have to confess and make promises. I prefer to excommunicate myself."

Is it true, as Greene believed, that "creative art seems to remain a function of the religious mind"? Modern novelists, for whom "the religious mind" is an alien idea, would not agree. But biographer and journalist Charles Moore, like Greene a Catholic convert, interviewed by Luke O'Sullivan in 2014, made the interesting observation that he felt estranged from contemporary authors who lacked a sense of tradition and "the importance of religion to our understanding of the world", stating: "I think they tend to be narrow, no matter how talented they are. So someone like Martin Amis has absolutely nothing of any interest to say, although he's a talented and intelligent man, because he doesn't have an interesting way of looking at the world."

Greene's way of looking at the world remains compellingly interesting, precisely because the characters in his best novels reveal the "appalling" truth about the human condition in a way that secular authors cannot do. This meant that for Greene, although, as he commented, literature "has nothing to do with edification", it does have everything to do with man's deepest impulses, hopes and fears, as he wrestles with his (often bad) conscience and his ultimate responsibility for the moral choices he makes.

That is why Greene will continue to be republished, rediscovered and appreciated by new readers, long after modern novelists like Martin Amis will have sunk into oblivion.

These readers, who know that great literature is an extended, complex metaphor for the haunting beauty and fearful cruelty of the world, will continue to ponder the heart-wrung words of Maurice in The End of the Affair, as he makes his own (characteristically Greene-like) prayer: "O God, You've done enough, You've robbed me of enough, I'm too tired and old to learn to love, leave me alone forever."

And they will continue to reflect on the plea of Scobie in The Heart of the Matter, who is representative of Everyman as he prays: "O God, I have deserted you. Do not you desert me."

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Francis Phillips. "Why Graham Greene's novels will stand the test of time." Catholic Herald (1 April, 2016).

Francis Phillips. "Why Graham Greene's novels will stand the test of time." Catholic Herald (1 April, 2016).

Reprinted with permisison of the Catholic Herald.

The Author

Francis Phillips was educated at Farnborough Hill Convent and then at Cambridge University. She is married with eight children, and is a freelance book reviewer and books blogger for the Catholic Herald website and magazine.

Copyright © 2016 Catholic Herald