To Beatrix in the Shadows: Johnny Town-mouse After 100 Years

- SEAN FITZPATRICK

One century ago, as the shadows of World War I were fading away, shadows were closing in on Beatrix. "

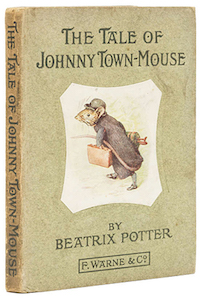

After nearly two decades of writing and illustrating an extraordinary series of children's books, Beatrix Potter was losing her eyesight. This, compounded with her labors on Hill Top Farm growing increasingly engrossing and with her publisher ever clamoring at the gate for more stories, Beatrix Potter came to the decision to compose and fully illustrate one last book. In the twilight of her vision, she wrote and (more notably) painted The Tale of Johnny Town-mouse and dedicated it with these cryptic words: TO AESOP IN THE SHADOWS. It was with this timeless tale, this fable, that Beatrix retired from her bright career as an illustrator into the shadowlands — she who had enjoyed and shared an eye so keen it had made her world the world of Aesop, the world of the Grimms, the world of Uncle Remus, and the world of Crane, Greenaway, and Caldecott. With Johnny Town-mouse, Beatrix Potter laid down her brush and withdrew from her watercolors into a sort of underworld, there to commune with Aesop in the shadows.

After nearly two decades of writing and illustrating an extraordinary series of children's books, Beatrix Potter was losing her eyesight. This, compounded with her labors on Hill Top Farm growing increasingly engrossing and with her publisher ever clamoring at the gate for more stories, Beatrix Potter came to the decision to compose and fully illustrate one last book. In the twilight of her vision, she wrote and (more notably) painted The Tale of Johnny Town-mouse and dedicated it with these cryptic words: TO AESOP IN THE SHADOWS. It was with this timeless tale, this fable, that Beatrix retired from her bright career as an illustrator into the shadowlands — she who had enjoyed and shared an eye so keen it had made her world the world of Aesop, the world of the Grimms, the world of Uncle Remus, and the world of Crane, Greenaway, and Caldecott. With Johnny Town-mouse, Beatrix Potter laid down her brush and withdrew from her watercolors into a sort of underworld, there to commune with Aesop in the shadows.

The Tale of Johnny Town-mouse is Beatrix Potter's fresh rendition of a tale that is as old as the hill where she ran her farm. Aesop's "The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse" is certainly a humble staple of Western Civilization, immortalized in the canonical constellation that is Aesop's Fables. In Potter's tale, we have a reversal of the traditional order, where the country mouse, Timmy Willie, is first and accidentally brought into town where he meets the polite, accommodating, yet passive-aggressive Johnny Town-mouse. After finding the circumstances of living in a human household insufferable, given the noise and alarums, cats and traps, and Sarah with the poker, Timmy Willie takes his leave, but not before describing his bucolic life to Johnny Town-mouse and securing a half promise for a visit from the socialite rodent. When Johnny does indeed arrive "spick and span with a brown leather bag" in the garden after the passing of winter, despite Timmy Willie's rustic and hearty hospitality, he finds the peace and quiet of the countryside unbearable and bundles himself back to the bustle of town.

For all of her imagination and invention, and even though she was losing her sight, Beatrix Potter never lost sight of reality — even its tensions and tragedies.

The awkward eloquence of Potter's retelling is what makes her little book a joy to read and her lush paintings a wonder to behold, all beginning with a country bumpkin crash landing on a formal dinner-party table. Beatrix Potter makes the ancient story live anew, drawing it out of the shadows to shine. And her style is as inimitable as ever. There are few writers who can capture the cheek and shame of being asked within a well-bred company if one's tail was insignificant due to having once "been in a trap?" Only the world contained in those diminutive Warne editions could present the bourgeois attitude of hoity-toity mice in evening dress poo-pooing the breakage of china since "they don't belong to us." Only the pert writing style of Beatrix Potter (she used the Bible as her model) could concoct the moment when Johnny Town-mouse calls Timmy Willie "Timothy William" with exasperation over his inability to be entertained. Beatrix Potter demarcates the lines between types, or classes, beautifully and delightfully with shrewd wit and social cognizance.The shift to Timmy Willie's garden is no less poignant. It is not surprising that Beatrix Potter takes something of a position with Aesop on the side of the Country Mouse, who says to his companion in his iteration, "You live in the lap of luxury, I can see, but you are surrounded by dangers; whereas at home I can enjoy my simple dinner of roots and corn in peace." The so-called dangers of the country embodied in cattle and lawnmowers pale in comparison to the feline and housekeeping dangers of the town, lending backbone to the preferences of Timmy Willie, who, for all he was worth, had not the stomach for the strange "but truly elegant" delicacies of Johnny Town-mouse's board, nor for his bed in a sofa cushion that smelled of cat. The sun and the lawn, and visiting Cock Robin, and the roses and pinks and pansies, and the violets and spring grass, were, and ever are, an intoxication, with "no noise except the birds and bees, and the lambs in the meadows." The Tale of Johnny Town-mouse is not a tale that builds up the town, but one that hunkers down in the country. And this was the last vision that Beatrix Potter chose to share with her readers before retreating with Aesop into the shadows.

While Johnny Town-mouse may be a haughty caricature of the well-to-do urbanite, Timmy Willie, on the other hand, provides a warm memory far removed from Johnny's universe, a memory hearkening back to simpler, rural times, when happiness was harder but more happily earned, and folks were grateful to have it. In these few short pages, Potter hearkens back to distant pioneering ages of crop and cattle, barnyards and dairies, fruits and flowers, and stone chimneys that smoked like patriarchal pipes. All by itself, this little story embodies, in Potter's paintings alone, one of the greatest criticisms of modern improvement, which questions whether progress can be truly called progress if its result is reminiscence or nostalgia for the way things were. There is a quality about the old-fashioned that the new-fangled can never mass-produce, and this quality serves as subject for some debate between country and city life, between the old and the new, between the light and the shadow.

While Johnny Town-mouse may be a haughty caricature of the well-to-do urbanite, Timmy Willie, on the other hand, provides a warm memory far removed from Johnny's universe, a memory hearkening back to simpler, rural times, when happiness was harder but more happily earned, and folks were grateful to have it. In these few short pages, Potter hearkens back to distant pioneering ages of crop and cattle, barnyards and dairies, fruits and flowers, and stone chimneys that smoked like patriarchal pipes. All by itself, this little story embodies, in Potter's paintings alone, one of the greatest criticisms of modern improvement, which questions whether progress can be truly called progress if its result is reminiscence or nostalgia for the way things were. There is a quality about the old-fashioned that the new-fangled can never mass-produce, and this quality serves as subject for some debate between country and city life, between the old and the new, between the light and the shadow.

The Tale of Johnny Town-mouse is a children's story, and it seems a shame to apply the idea of it being a satire on the extravagance of city living, or the purity and pleasures of country living, or the need for some degree of balance and acknowledgement between societal predilections and interactions. It is too good to require any such design. John Keats famously wrote, "We hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us." The same can be said of literature. Much of children's literature has a palpable design, imposing moralist medicines that are rightly nauseated — especially by children. Youngsters know when they are being inveigled; and so, the whole point of children's literature is not to force any design upon them, but to allow them to encounter things as they are and on their own. It is the ultimate testimony to Beatrix Potter's works and her approach in those works that children have loved them for a century.

For all of her imagination and invention, and even though she was losing her sight, Beatrix Potter never lost sight of reality — even its tensions and tragedies. Peter Rabbit's father was put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor. Jemima Puddle-Duck's eggs were devoured by her canine rescuers. Squirrel Nutkin was mutilated by Old Mr. Brown. The social anxieties and pressures of hospitality are palpable in Duchess and Ribby — and, of course, Timmy Willie and Johnny Town-mouse. The world of Beatrix Potter is the real world: moral, but not moralistic, a world of hunter and hunted, of anecdote and accident, of tension and delight, of trial and error, of hesitation and discovery. Her honesty and humor are radiant in her works and it is precisely her honesty and her humor that make her works worth reading. After one-hundred years, The Tale of Johnny Town-mouse deserves revisiting, especially as it marks a turning point in the career of one of the great children's book illustrators and authors.

Take the time to enjoy this delicious dichotomy of a tale during these delicious summer days and enjoy it with your spouse, your children, your grandchildren, your friends. Though Aesop lies relegated to shadow in one way or another, as the nearly-blinded Beatrix Potter suggested, let not her last fully-illustrated tale be lost to sight. Let it remain in the light even after one-hundred years, as its author watches, even now, from the shadows.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Sean Fitzpatrick. "To Beatrix in the Shadows: Johnny Town-mouse After 100 Years." Crisis Magazine (August 6, 2018).

Reprinted with permission of Crisis Magazine.

The Author

Sean Fitzpatrick serves on the faculty of Gregory the Great Academy in Elmhurst, Pennsylvania. He teaches Literature, Mythology, and Humanities. He lives in Scranton with his wife, Sophie, and their six children.

Sean Fitzpatrick serves on the faculty of Gregory the Great Academy in Elmhurst, Pennsylvania. He teaches Literature, Mythology, and Humanities. He lives in Scranton with his wife, Sophie, and their six children.