Sigrid Undset's World

- REV. JOSEPH KOTERSKI, S.J.

What does it take to bring an undaunted religious perspective into the land of high literary culture? In Sigrid Undset (1882-1949) we have a Nobel laureate novelist who was mindful of all the main issues and whose medieval works have been making a comeback.

One occasionally meets theoretical atheists, people who reflectively profess that there is no God and may even try to harangue you with their favorite proofs. But far more often one meets practical atheists, people who feel quite strongly that they have no need of God, and live for all practical purposes as if there were no God. This practical atheism seems to be a rather recent phenomenon, somehow connected to the overconfidence that comes from the enormous control we have over so many elements of the world: our daily sustenance is rarely in jeopardy, our basic safety is unthreatened, our powers of choice and the fields where we can exercise our discretion are enormous. Turning to God in our needs would be a sign of neediness we would rather be without.

One occasionally meets theoretical atheists, people who reflectively profess that there is no God and may even try to harangue you with their favorite proofs. But far more often one meets practical atheists, people who feel quite strongly that they have no need of God, and live for all practical purposes as if there were no God. This practical atheism seems to be a rather recent phenomenon, somehow connected to the overconfidence that comes from the enormous control we have over so many elements of the world: our daily sustenance is rarely in jeopardy, our basic safety is unthreatened, our powers of choice and the fields where we can exercise our discretion are enormous. Turning to God in our needs would be a sign of neediness we would rather be without.

This basic approach to life can often be harder to challenge than the declarations of the professed atheist. Until the person begins to feel an absence, an emptiness down deep, the habits of self-reliance that have been culturally reinforced by such easy personal access to material goods and to the sophisticated technology of sensory stimulation as we e as joy in the West today, any talk about turning to God in our neediness falls on deaf ears. And yet the situation is not unlike the predicament Israel experienced when it finally reached the promised land: the Lord had seemed so close while the chosen people wandered in the desert, for the Lord daily provided their food and drink. But once in the land that flowed with milk and honey, the very fertility of their new homeland and their easy access to the means of their sustenance allowed the people to grow forgetful of God. For this reason the sermons of Moses in the book of Deuteronomy constantly attack the temptation to worship the native gods of the place as if they had bestowed the gifts of the land upon the people and not the Lord (e.g. 6:4-25 and 8:1-20).

The virtual absence of any such religious perspective on today's literary landscape might be measured by scanning some cultural index like the New York Times Review of Books. It is not that religious novels or essays that challenge cultural decadence are not written, but seldom are they of high enough quality to have broad influence or to deserve this level of review. What does make the grade for good story-telling or effective cultural analysis rarely bears a religious perspective. Yet there is a willingness by an index like this to respect a religious point of view when, for example, Robert Coles1 offers his reflections on the religious imagination. The hunger for insight about the problem of evil, to take another case, is evident from the record-setting persistence of F. Scott Peck2 on the Times' list of paper-back best-sellers.

Conversion and Convictions

What does it take to bring an undaunted religious perspective into the land of high literary culture? In Sigrid Undset (1882-1949) we have a Nobel laureate novelist who was mindful of precisely these issues and whose medieval works at least have been making a comeback.3 She grew up in the nominally Lutheran land of Norway and in a family that kept church at arm's length. Her parents were not particularly anti-religious but felt skeptical of the state-supported clergy. Of herself she reports from her youth a respect for things religious, and a sense of there being something true in all of them. She even invented for herself a kind of "humanistic private religion."

Her journey from this position to her reception into the Catholic Church on November 24, 1924 took her through the wilds of a stormy marriage, an abortion, a divorce, and the drudgery of office-work to support her children on her own until her fiction brought her enough income to live on as a writer. Her 1936 essay4 explains that she received no shocking illumination about the divine, but that gradually a breaking in of the light, the grace to accept as true what her intellect already recognized as true: that God is absolutely other than this world, yet also a person in communion with me, whose ways were not my ways, but who could lead me into his ways. Her early acquaintance with the free thought and free love movements had left her abandoned. She had tried the route of self-reliance and come up short. She finally felt a neediness that no infusion of busy-ness or material goods could remedy.

The bulk of her novels, some set in medieval times, others using contemporary scenes, tend to be instances of the same combat of Christian civilization against paganism which she lectured about in her resistance to Nazism. Modern paganism, she felt, was more nefarious than ancient, which was still religious at heart. The new paganism had at its core a hostile rejection of God, a repudiation of any admission of human insufficiency and a resentment at what appeared to be enslavement to a higher power. Most of its free-thinkers, she discerned, were at bottom angry with God, angry because the world was not governed in accord with their notions of how the world should be governed. By contrast, she tells us, Christianity's high esteem for mother-hood, and its religious consecration of marriage, helped more than anything else to open her eyes to the truth of the faith.

Let us here briefly recount the story of one of her medieval works and then one of her modern novels as samples of her insight. It will help to remember the astute observation G. K. Chesterton made in The Superstitution of Divorce, "The morality of a great writer is not the morality he teaches, but the morality he takes for granted. . . . The fundamental things in a man are not the things he explains, but rather the things he forgets to explain."5 This is true, I think, of Undset. As she develops themes like loyalty, obedience and the genuine liberation that comes from truthfulness, we see the maturity of her Christian understanding. She has a Catholic respect for the generally religious mind and she handles even nature-worship in a way we might not expect but cannot help admire. Nature-worship is inevitable and appropriate (for it is a recognition of a higher power than ourselves) until we understand that nature has neither thought nor feeling for us, and that it is only the creator of nature that really loves us.

Medieval Novels

|

Sigrid Undset |

||||

She wrote 36 books, the mediaeval novels being one part. Another part are her contemporary novels of Kristiania (now Oslo) and Oslo between the turn of the century and the 1930s, the third part being literary essays and historical articles. Her authorship is wide-ranging and of remarkable depth and substance. None of Sigrid Undset's books leaves the reader unconcerned. She is a great storyteller with a phenomenal knowledge of the labyrinths of the human mind.

|

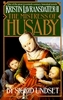

Kristin Lavransdatter is set in 14th century Norway, and the political currents of the period have their impact on the story. Kristin grows up during a period of steady peace and firm order that is the result of Haakon V's wise rule. The peace of the society has been achieved by several generations of concern for the common good and the cultivation of the new religion.

In many ways her father Lavrans is still a pagan soul, but one being softened by Christianity. He embodies the virtue of piety. He has a deep-seated respect for religion and civil responsibility, for loyalty in family and social matters. In his concern to observe the Christian marriage laws relatively new to Norway, one can see 14th century Norway's growth in the idea of justice which missionary monks had brought to Scandinavia. His ancestors may have been among the great families of Norway, but he neither has nor wants an official post or formal part in the political life of the country. Undset directs us to his inner life instead. His greatness is a quiet strength which all who deal with him sense. It often brings out their better side. Even when his wife Ragnfrid and his daughter Kristin shatter the trust he has given them, his confidence in God never deserts him.

The central plot of the novel, the love-story of Kristin and Erlend, the knightly figure of her dreams, emerges against the backdrop of the secure order Lavrans has created at Jorundgaard, their family estate. From her chance meetings with the fairy lady, a vestige of Norway's nature religion, and then the mysterious Mistress Aashild at age seven, we begin to see both the hold religion has on her and the self-infatuation that crouches in her psyche, waiting to ensnare her. It will dominate her personality until she can humble herself to accept assistance coming from quite a different quarter. And yet the Christian faith has a deep resonance within Kristin too. She is docile enough to take guidance from Sira Eirik the Priest and she forms a habit of prayer. She finds it easy to pray over the beauty of things and to remember her Creator. As she grows older she discovers in Brother Edvin a friend who understands the movement of her soul more deeply than she has risked doing herself.

The problem is that Kristin is not free to marry Erlend. Her father had made a match for her with Simon Andresson, a good man but not the romantic figure she had secretly promised herself. Once Lavrans noticed that a playmate from her childhood, Arne Gyrdson, has stirred up some affection in the budding Kristin, he trundled her off to the sisters at Nonnesaester, hoping she would forget Arne and prepare herself for life with Simon. But it is there that she first meets Erlend. Love sweeps them away and they pledge always to be true to each other. Blinded by the insistence on having her will, Kristin can see neither the duplicity of her knight nor the stain on her own character from all the scheming and defiance with which she forces her father to buy her release from the agreement already contracted with the Anders clan. As we watch Erlend trying to free himself from the clutches of Eline Ormsdatter, the mistress by whom he has had two children, we find that he is only being true to form in luring Kristin. Putting aside any chivalry still left to him, the rake soon has his will with a most willing Kristin.

By the time their half-truths have tricked Lavrans into breaking her engagement, they have together become responsible for Eline's death but fabricate an elaborate story to shield themselves. She keeps up all the appearances of propriety so that she can wear a maiden's garland at her wedding Mass, but the baby kicking in her womb seems to be prodding her to acknowledge the wrong she has done her father and her God. Paralyzed by lie after lie, she feels herself unable to tell the truth and simply hopes the truth will be discovered. She prays for divine protection, but her will is divided, anxious to set things right yet even more desperate to have things her own way.

The whole novel is a study of how truth, though painful to put back in place, can always free, but how anesthetizing lies invariably enslave. The partial truths Kristin gives as reasons for refusing to marry Simon prompt her mother Ragnfrid to explain the coldness so evident between her and Lavrans. She too had already given herself to someone else before her marriage, and with each winter she seems to find herself colder toward her husband. Now the daughter on whom he lavished his affection instead has betrayed him and is becoming ensnared in her own web of lies. The pattern of her married life is thus set on their wedding day.

To keep up her pretense she refuses to tell Erlend that she is already with child but then blames him for not seeing what everyone else must already see. When a grasp of her waist during a dance tells him the truth, her look, accusing him of far more, silences him, and their untruth with one another binds them to a different relation than that to which the sacrament intended to yoke them.

Mending these torn souls is a long task. Her will only begins to be re-directed when his political fortunes are shattered in an unsuccessful Norwegian rebellion against Swedish domination after Haakon's death. Stubborn by temperament and willful by habit, she holds back from making the repentance she longs for because she cannot believe someone as selfish as she can be saved. Only Erlend's brother, the monk Gunnulf, is able to speak deeply to her of the need to be humble before the mercy of God. He encourages her to make a pilgrimage to Christ Church in Nidaros and there to seek from the Archbishop forgiveness for her long-hidden role in the death of Erlend's mistress. Praying to St. Olav in thanksgiving for protection of the son she was already carrying on her wedding day, she has a humbling vision of what accepting God's mercy means.

The contrition she comes to feel is deeply painful, but it proves a rejuvenating power. In every aspect of her life she needs it to struggle against the forces of darkness: in her marriage to Erlend, in mothering her seven sons and loving his other children, and in seeking a reconciliation with her father. But with each step grace is working and she can thank God for showing her a world better than her enslaving lies had once fashioned. Like today's thirty year olds returning to the nest, her decision to ask her father's forgiveness costs her much of her pride. But it evokes from him an affection she had long missed:

"Grieve no more for anything you have done to me which you must regret, Kristin. But remember it when your children grow up and you perhaps feel that they don't behave toward you as would be fitting. And remember then too what I told you of my own youth. Your love for them is steadfast — but you are most stubborn when you love most."

A more difficult relation for her to heal is that with her husband. Unasked, memory keeps reminding her that he is responsible for her years of misery. Toward others she is above small-minded pettiness, but toward him small, stinging allusions come as naturally as violent outbursts about his failures and infidelities. Only slowly does the love of God that has been growing within her bring on the realization that her father was right: she has treated him the worst because she loved him the most. In fact, her own carping had provoked his political ambitions, and her shrewishness had driven him to his infidelities. Only her admission that she too shares the guilt for their miseries opens a way back.

But this truthfulness is no guarantee of easy success, for the process of healing is extremely complex, especially in freeing the imagination from bitter hatreds and long nursed sorrows. After the promises of a fresh start faded, Kristin "sat and made room for the old bitter thoughts, as if they were pleasant companions." Desolation returned to her in the form of self-righteous comparisons of his sufferings with hers, especially having to endure popular contempt and then seeing her sons admire so much the father whose real story she alone knows. Only when he dies in the act of protecting the honor of the wife with whom he could not stand to live, is the last blockage of her heart removed, and then it is too late. She yields her place at Jorundgaard to her daughter-in-law and makes pilgrimage again to Nidaros to live the remainder of her life among the sisters there, a life of humble obedience that might check the reassertion of her pride.

There is simply no substitute for telling a good story, but what Undset's religious perspective brings to bear is an appreciation of the human need for grace. To insist on having life entirely on one's own terms is an abiding temptation, but the process of being caught up short and being shown the way back to a humble use of one's freedom invokes the operations of providence. What makes a Nobel Laureate of Undset is the entirely authentic penetration of her heroine's psyche and its natural movements even while tracing the workings of grace.6

Undset's Modern Novels

Most of Undset's contemporary novels were written in light of her disenchantment with early 20th century feminism. In essays from the same period she explains her sense of the need to combat various fallacies of the modern age, including the substitutes for religion that had initially attracted her to the free love and free thought movements. Her own conversion to the Catholic Church, she tells us, began when she came to see that only the Church respected the true dignity of women. The liberal Protestantism of her day she dismissed as mere "wishful thinking."

In The Faithful Wife, to take but one instance, we have a couple nourished on such typical early modern views as open marriage and easy divorce. The heroine's parents, in fact, are prime movers in the liberalization of Norway's divorce laws. But Sigrid and Thali's own marriage goes along sleepily for sixteen years, each partner pursuing a private career, and their union experienced mainly in common meals, the bedroom and sometimes a pleasant vacation together. Sigrid, however, falls for a young Catholic girl, whom he impregnates but who will not marry him. Thali is shocked — in fact, dazed in a way she never expected, but separates from him in order to leave him free to wed the girl.

Their lives diverge for a period of a few years. In her humanitarian kindness, she takes pity on a clerk of hers whose husband is no good and who falls ill after childbirth. She feels re-awakening in her the feelings of motherhood she had once hoped for whenever she used to care for nephews and nieces, but her own new romantic dalliances keep her imprisoned. At length she gives up her lover — "It isn't true" — and she finds herself left with her clerk's child when the poor child's father deserts and the mother dies. Sigrid finds her husband is constantly on her mind, but she cannot imagine how a reconciliation could ever be brought about.

It has turned out that his child's mother has died as well, leaving him to raise her. So each of them has a child, but each is seriously incomplete as parents. The renewal of their acquaintance forces a realization of the truth — "It can never be the same as before." In fact, it is their duty to make sure it is not the same as before, for both had pretended then that they were complete in themselves. They now realize, and must live out the lesson, that marriage is the union of two individuals in themselves incomplete and imperfect, uniting to complete and perfect one another. They find they must be far more honest and truthful with one another, that they must truly confide in one another about their expectations and desires and all the rest, and not refrain from sharing these important parts of themselves out of a vain pride or a false idea of their own strength.

The novel ends, not on any sugar-sweet bed of roses, but on a promise and a hope, and with at least the prospect that the truth, however much it hurts, has set this couple free to try again. This is very typical of Undset's view of human nature: it dearly needs what Christianity has persisted in teaching about its full development. Marriage, for instance, the subject in The Faithful Wife, has suffered much from the experimentation of well-intentioned social engineering. But the pliability this experimentation has assumed to exist in human nature does not exist. Even plastic does snap when bent too far, and human malleability is not designed to accommodate the theories of free love and open marriage.

Observations

The world of Sigrid Undset's imagination, created early this century, is a telling judgment against great social tragedies that need not have been. She herself lived out such a tragedy and then found the grace of Christian healing in her art. When she wrote, she tried it seems, to repair some part of the damage.

Our world stands much in need of just such reparative work. Paganism has returned to the assault, not just in the fabled fjords of Scandinavia but throughout the west, and with considerable success. It has arisen as a popular movement in culture to satisfy a hunger for mystery and beauty many people have increasingly felt over the last generation. For it has been a period in which religious leaders, heeding the voice of the same basic rationalism that once entrapped Undset, have become embarrassed about being thought superstitious and have often allowed popular devotions with all their warmth to disappear. Paradoxically, in wanting to avoid even the appearance of paganism, those who have promoted the rationalization of religion have made possible the massive return of paganism during their watch.

The reparation needed is a restoration in head and in heart, in creed and in cult. The return of paganism may serve to remind us of the natural drive of the human heart to be religious, but Christianity has always taught that we need something more than merely to be religious — our religion must also be true. What is needed is the supernatural, not the superstitious, with beauty as the charm to bring bent souls, cold and unwilling, to turn again to the One Who is without shadow of turning.

Endnotes

- Robert Coles, The Spiritual Life of Children, reviewed by Herbert Mitgang in New York Times Review of Books, Nov. 21, 1990.

- F. Scott Peck, The Road Less Travelled, on the list of paper-back sellers for 461 consecutive weeks as of September 6, 1992.

- Kristin Lavransdatter is still in print, as are some of Undset's other books, including: Stages on the Road, Four Stories, Happy Times in Norway, Men, Women and Places, and Saga of Saints.

- Sigrid Undset, "They Sought the Ancient Paths" (1936).

- G. K. Chesterton, The Superstition of Divorce. (NY: John Lane, 1920) p. 40.

- In a sense The Master of Hestviken is even more remarkable, for there Undset does for the masculine psyche what Kristin Lavransdatter attempts for the feminine.

Related Articles

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Joseph Koterski, S.J. "Sigrid Undset's World." The Dawson Newsletter vol. X no. 4 (Fall, 1992): 6-9.

This article reprinted with permission from the author, Joseph Koterski, S.J.

The Author

Father Joseph W. Koterski, S.J. is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Fordham University and Editor-in-Chief of the International Philosophical Quarterly. His areas of interest include Metaphysics, Ethics, History of Medieval Philosophy. Among his books are An Introduction to Medieval Philosophy: Basic Concepts. For The Teaching Company he has produced lecture courses on Aristotle's Ethics, on Natural Law and Human Nature, and Biblical Wisdom Literature.

Father Joseph W. Koterski, S.J. is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Fordham University and Editor-in-Chief of the International Philosophical Quarterly. His areas of interest include Metaphysics, Ethics, History of Medieval Philosophy. Among his books are An Introduction to Medieval Philosophy: Basic Concepts. For The Teaching Company he has produced lecture courses on Aristotle's Ethics, on Natural Law and Human Nature, and Biblical Wisdom Literature.