Belletrist and the beast

- FATHER RAYMOND J. DE SOUZA

For those who love the English language, the Catholic faith and practice journalism, Evelyn Waugh would be the perfect patron saint, save for the fact that he was such an unpleasant person he would never be canonized.

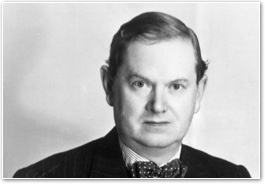

Evelyn Waugh

Evelyn Waugh1903-1966

Fifty years ago, on April 10, 1966 — Easter Sunday that year — the British belletrist Evelyn Waugh died. For those who love the English language, the Catholic faith and practise journalism, he would be the perfect patron saint, save for the fact that he was such an unpleasant person he would never be canonized.

Most Waugh admirers know of his retort to his fellow writer and prolific correspondent, Nancy Mitford, who questioned how he could reconcile his rude behaviour with his Christian faith. Waugh invited Mitford to consider if he lacked the grace of the sacraments, how much more horrible he would then be. Salvation, as Waugh worked out in his novels and essays, most famously in Brideshead Revisited, was for those who needed it, and in being needful of divine grace, Waugh was happy to place himself at the head of the queue.

Waugh belonged to that happy generation of the literary journalist, who was sent abroad to cover wars, the enthronement of Ethiopian emperors or the exhibition of the relics of long dead saints. He would send home elegant essays of equal parts luminous prose and delightful wit. Actually, the wit could often be brutal, but Waugh thought it best to smile while savaging someone. Brideshead and his Second World War trilogy, Sword of Honour, are his best-known works, both receiving treatments as television productions.

Yet my favourite books are his historical novels of two saints, Edmund Campion, about the Jesuit martyr under Elizabeth I, and Helena, about the mother of Emperor Constantine. Waugh opens his Campion novel with the scene of another young man at Oxford chosen to give a prestigious allocution before the Queen, which begins a career full of civil and ecclesial honours. With a devastating account of the price paid for a comfortable life, he writes, "There but for the grace of God went Edmund Campion." Waugh became celebrated in time by the British establishment, but retained his suspicion that worldly plaudits came at the sacrifice of eternal verities.

In his historical novel, Helena, he creates a marvellous conversation between Constantine and Helena, the empress dowager, whom we know as St. Helena. Constantine is fretting about Rome, and already planning to move east to establish his eponymous capital on the Bosphorus.

Waugh became celebrated in time by the British establishment, but retained his suspicion that worldly plaudits came at the sacrifice of eternal verities.

"I hate Rome," he says to his mother. "I think it's a perfectly beastly place. It has never agreed with me. Even after my battle at the Milvian Bridge when everything was flags and flowers and hallelujahs and I was the Saviour — even then I didn't feel quite at ease. Give me the East where a man can feel unique. Here you are just one figure in an endless historical pageant. The City is waiting for you to move on."

Rome's role, shifting from an imperial to a religious capital, is to remind the great men of history that their time is passing, their pretensions just that. Waugh, who loved the ancient ritual of the Catholic faith to which he converted, would have been dismayed that the coronation of a new pope no longer includes an official who admonishes him three times, "Sic transit gloria mundi" — the glory of the world passes away. Dying in 1966, Waugh already saw enough of the coming reforms in Catholic life to be deeply dismayed, even disconsolate, and frequently dyspeptic.

In 2016, the Waugh novel that perhaps speaks to us most directly is Scoop, the fantastic tale of how a foreign correspondent fanned the flames of war to boost sales back home at the Daily Beast. The satire highlights the sordid side of Fleet Street and the sensational culture of the competitive press. To "feed the beast" — the insatiable need of the modern media for what we now call "content" — provided the impetus for the title of the fictional tabloid. That there is now an Internet news portal of that same name is proof that satirists sometimes get to the truth well ahead of reporters.

There might be a successful website called The Daily Beast, but the journalists who fed the beast in the days of Waugh are increasingly rare. The beast is more ravenous than ever, with stories posted online not by date, but by "x minutes ago." Yet the beast has also devoured the circumstances that made the journalism of Evelyn Waugh, to say nothing of his novels and volumes of letters, possible.

Waugh died at only 62, so it is possible to imagine him living long enough to see the early Internet and cable news. Better that he died when he did; it might have distressed him more than liturgical reform.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "Belletrist and the beast." National Post, (Canada) April 12, 2016.

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "Belletrist and the beast." National Post, (Canada) April 12, 2016.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post and Fr. de Souza.

The Author

Father Raymond J. de Souza is the founding editor of Convivium magazine.

Copyright © 2016 National Post