The contradictions of Muhammad Ali

- FATHER RAYMOND J. DE SOUZA

As implausible as it might seem, the laudations lavished upon Muhammad Ali in death are even more extravagant than those he lavished upon himself in life.

I am an admirer, and recommend upon the death of the self-styled "greatest" a re-reading of Norman Mailer's The Fight or the documentary film When We Were Kings to remember something of how remarkable the Ali phenomenon was at its peak.

I am an admirer, and recommend upon the death of the self-styled "greatest" a re-reading of Norman Mailer's The Fight or the documentary film When We Were Kings to remember something of how remarkable the Ali phenomenon was at its peak.

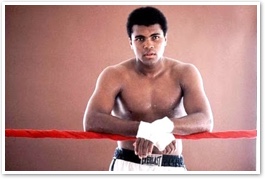

Ali, if not the greatest, was the largest personality in the early years of our celebrity culture. He was large enough to contain immense contradictions. He was pretty in a sport that disfigures. He was graceful in a place of brutality. He was brainy in a battle of brawn. He was middle class, but usurped the mantle of the oppressed against opponents who had been genuinely poor. He was sincerely religious, but unstable in family life. He was the great athlete who showed greater strength in weakness and disease than he did even in the ring.

There is much to admire. The exaltation of Ali though tells us as much about our culture as it does about him.

The great struggle for which Ali deserves most praise was his willingness to suffer exile from boxing for his refusal to be drafted for the war in Vietnam. He took a stand on principle that cost him a great deal, not knowing then whether he would ever return. The triplex battle with Joe Frazier, the rumble with George Foreman — all that lay in an uncertain future when Ali sacrificed his title.

What will president Bill Clinton, eulogizer of Ali at Friday's funeral, say about all that? Clinton avoided the draft in such a manner as to, as he wrote then, preserve his "future political viability." Clinton was both ambitious and cowardly; Ali was the former, but never the latter. Nevertheless, it will be a great show, as Clinton is a superlative preacher in the black church — far better than President Barack Obama. His eulogy for Coretta Scott King some years back was one of the best I have ever heard.

Ali himself was the great showman, but much of the show was not fit for mature audiences. He was insulting and offensive, which was widely excused by his wit. He shamelessly exploited the distinction between the "light-skinned" and "dark-skinned Negro" with vicious verbal assaults on his fellow black boxers. Ali's great friend and ally in civil rights, the broadcaster Howard Cosell, was eased out of Monday Night Football in 1983 for an off-hand and innocent remark. He had called a black football player a "little monkey" (a term he had used for a white player before). Eight years earlier, Ali spent months deriding Frazier as a "gorilla," greeted not with outrage but widespread hilarity. Perhaps Ali was the greatest trash-talker of all time, but that is not a compliment.

That was the show. Ali realized just in time that there was plenty of room in popular culture for playing the braggart, the buffoon and the bully. He adapted his act from Gorgeous George, the professional wrestler, and spread abroad the theatrical premise of pro wrestling, that one could be maximally outrageous without consequence, everything being scripted. The decline of boxing as a sport after Ali was precipitous. Who even knows who the heavyweight champion is today? In contrast, Ali's showboating legacy has gone from strength to strength, from professional wresting itself — which is a much bigger cultural phenomenon than boxing today, and which Ali was happy to embrace — to reality television, to the first presidential candidate in Ali's rhetorical wake, Donald Trump.

He took a stand on principle that cost him a great deal, not knowing then whether he would ever return.

Ali's courage in the 1960s was rewarded with extraordinary good timing in the 1970s. One of the most astonishing shifts in America was, after the resolution of the civil rights movement, the enormous popularity of black entertainment figures. In the 1980s, Oprah Winfrey, Bill Cosby, Eddie Murphy and Michael Jackson were all dominant. America wanted black heroes, and Ali was at the ready, having earned it. By 1996, when he lit the torch at the Atlanta Olympics in a truly inspiring moment, he was a living relic of the civil rights movement.

In 2007, Joe Biden was roasted for saying of Barack Obama, running for president after only two years in the U. S. Senate: "The first sort-of mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy — that's a storybook man!" It could have been Ali speaking about himself decades earlier, a man who wrote his own story. He stood up for himself by disparaging his black opponents as being dumb and dirty and dangerous.

And the famous name? The man who prided himself on being utterly unique adopted the world's most common name. The "slave name" that he cast aside — Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr., was his father's, who in turn was named after one of the great anti-slavery activists and abolitionist politicians of the Civil War period.

Ali was large enough to contain the contradiction. Indeed, he was the largest.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "The contradictions of Muhammad Ali." National Post, (Canada) June 7, 2016.

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "The contradictions of Muhammad Ali." National Post, (Canada) June 7, 2016.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post and Fr. de Souza.

The Author

Father Raymond J. de Souza is the founding editor of Convivium magazine.

Copyright © 2016 National Post