Alexander Hamilton: From Caesar to Christ

- DONALD D'ELIA

The dilemma for Hamilton was a new one and the most formidable of his life. He must meet Burr, pistol in hand, on the heights of Weehawken, or appear to the world not only cowardly but unworthy of the moral leadership of the great empire which was his creation.

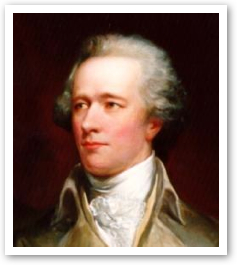

|

Alexander Hamilton

1755-1804 |

Where now. Oh vile worm, is all thy boasted fortitude and resolution? what is become of thy arrogance and self-sufficiency? Why dost thou tremble and stand aghast? How humble, how helpless, how contemptible you now appear .... Oh, impotent presumptuous fool! How darest thou offend that omnipotence, whose nod alone were sufficient to quell the destruction that hovers over thee, or crush thee to atoms? ... He who gave the winds to blow and the lightnings to rageeven him I have always loved and servedhis commandments have I obeyed and his perfection have I adored. He will snatch me from ruinHe will exalt me to the fellowship of Angels and Seraphs, and to the fulness of never ending joys. [1]

Alexander Hamilton wrote this not in the final, tragic years of his life, after his disillusionment with politics and rebirth as a Christian, but in 1772, when as a boy of fifteen in St. Croix, West Indies, he described his reaction to a terrible hurricane that slammed into the islands and wrecked the Danish settlement on the night of August 31. [2] Even so, the labored, youthful account, modelled after the heroic compositions of Pope and his other favorite authors, was prophetic of the mature Hamiltons deep sense of contingency and trust in God after his political and other battles had been lost. For, as we shall see, when Hamilton lay mortally wounded after his duel with Aaron Burr he truly believed that Christ would snatch me from ruin and exalt me to the fellowship of Angels and Seraphs, and to the fulness of never ending joys. And, on July 12, 1804, after having received Holy Communion from Episcopal Bishop Richard Moore, Hamiltons soul found its peace at last.

Hamilton died in New York City, surrounded by his wife and seven children and mourned by a nation. Half a century earlier, his coming into the world, on Nevis Island, British West Indies, had had none of this celebrity. Indeed, Hamiltons parentage, as John Adams and others sneered, was irregular. [3] He was the son of James Hamilton and Rachel (Fawcett) Levine, who, separated from her legal husband, was prevented from a licit union by her failure to obtain a divorce and who soon found herself deserted by the boys neer-do-well father. At age eleven Alexander lost his mother too, when the poor, heart-broken woman could struggle no longer against her deepening misfortune.

Orphaned as he was, young Hamilton was thrown on the charity of the island gentry, and in 1769 he was placed in the trading house of Nicholas Cruger as an apprentice clerk. Cruger was one of the most prosperous merchants of St. Croix. His store in Christianstadt was the center of the Islands trade, and Hamilton soon learned to excel in record-keeping, buying and selling, and all the other activities of the bourgeois merchants. Perhaps, as one of his biographers, Nathan Schachner, has speculated, Hamiltons Calvinist inheritance on his mothers side may have fitted him for the economic life, as a model apprentice clerk in the early years and as the architect of American capitalism in the post-Revolutionary era. In any case, to a boy in his straits there was no alternative to success. [4]

Nor was the lads education neglected. Dr. Hugh Knox, the Presbyterian minister who had been so helpful to his mother, saw after his education in Latin, mathematics, and French; and in 1772 Dr. Knox and others arranged for him to continue his studies on the mainland. Hamiltons first choice was Princeton, where Dr. Knox had graduated. However, the College would not accept his proposal for an accelerated program of study, so the West Indian decided on Kings College in New York. There is no doubting that Hamilton was serious about college, yet he was ambitious and impatient to make his way in the world, and back home he had revealed to a close friend that he would willingly risk my life, though not my character, to exalt my station. [5] All that he needed was an overpowering cause, a noble one that he could exploit to the fullest, and win that glory that he had read about in the pages of Caesar and Plutarch while an orphan boy in St. Croix.

The mainland colonies were astir those days with such a cause. In May of 1773 Parliament enacted the Tea Act, threatening to give the British East India Company a monopoly on the colonial market. This was only one of a long train of laws, passed since 1763, which colonial spokesmen held to be unconstitutional. Hamilton agreed. Dr. Knox and other opponents of Parliaments new imperial policy in St. Croix had already explained to him how all Englishmen were being deprived of their historic rights by Lord Norths arrogant stratagems. But it was the Boston Tea Party of December 1773 which led Hamilton as a student at Kings to become personally involved in the crisis by writing his Defence of the Destruction of the Tea and publishing it in Holts Journal, where it attracted the attention of many patriot New Yorkers over the next few months. He contributed still other articles, was emboldened to give public speeches on Parliamentary oppression, and determined to take an even more active role in the controversy with the mother country. [6]

It was this last resolution which caused Hamilton to defend the Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, in another pamphlet, and to attack the liberal Quebec Bill of 1774, which recognized the Roman Catholic Church in Canada, as a ministerial conspiracy to destroy the Protestantism of the colonist by establishing popery among their neighbors to the north. Here, in his Remarks on the Quebec Bill, which reflected the thinking of the Continental Congress itself, the eighteen-year-old Hamilton revealed not only the Whig sentiments of his West Indian tutor, Dr. Knox, but his prejudices as well. It is ironic that, in taking this line of argumentor, better, in making this emotional outburstthe man who would become the new nationss most vocal spokesman for centralized, Federal power helped in this instance to bring about the opposite effect, as the French Canadians, smarting at this kind of treatment, remained loyal to Britain and would have nothing to do with anti-papist bigotry. [7]

Hamilton had found his noble cause, liberty, and his pamphlets and speeches were serving it well, at least in keeping Parliamentary tyranny before the public eye. But there was still his dream of military glory, of Casear-like conquests that would rescue him from his obscure and shadowed beginnings. I mean to prepare the way for futurity, he had confided to a friend in St. Croix. I wish there was a war. [8] Now, in March of 1776, after the blood-letting at Lexington and Concord, there was one, and Hamilton used his connections among the New York Sons of Liberty to obtain the rank of captain of artillery in the local militia. Never, as it turned out, was a political appointment more fitting, since he had studied all about artillery and ballistics on his own, like the self-taught Henry Knox, and was to serve the Revolutionary cause with distinction. The opportunity to excel at arms soon presented itself. [9]

In the retreat across New Jersey later that year, Captain Hamilton was assigned to Washingtons rear-guard on the banks of the Raritan River and handled his battery with such skill and gallantry as to allow the main body to withdraw safely to Princeton. General Washington himself was impressed, although in the end it was Hamiltons other talentshis gift for writing and keen intelligencewhich led the commander-in-chief on March 1, 1777 to name the young captain his aide-de-camp with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. At twenty Hamiltons meteoric rise to power had begun. It appears so dramatic that perhaps one can understand the temptation of some writers to charge that Hamilton, who was born while Washington was in the Barbados, was none other than the Generals natural son. (10)

As secretary and aide to Washington, the Virginian being for all intents and purposes secretary of war as well as commanding general of the army, Hamilton soon became privy to the inner workings of the Articles of Confederation government and the military system, both of which he now sought to purge of their defects by constructive reforms. Even at this early date, Hamilton called for a constitutional convention, apparently the first proposal of its kind, to centralize power in Congress; and urged the establishment of a national bank in a letter to Robert Morris, the new nations superintendent of finance.(11) It was, of course, only as Washingtons trusted adviser, his intimate rather than merely his aide-de-camp; that Colonel Hamilton could presume to write to the older leaders of the Revolutionary cause and indulge his pet theories. Or, more directly, Hamilton began now cleverly to manipulate Washington who, at forty-five, was more than twice his age and who seems to have developed from the start a fatherly attachment to the brilliant young officer. It is this manipulative ability, this capacity to use people-Washington and many others-as a means to what he conceived to be a higher end, that describes Hamilton best in his vigorous middle period. This higher end or purpose of Hamilton in the years from, say 1777 to 1801, was the construction of his own political utopia in America.

From his vantage point in Washingtons military household, where for four years he was the Generals alter ego, Hamilton could see the critical weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation government and the men who administered it. After the War, and a term in the Continental Congress (1782-83) where more internal problems became disturbingly apparent, the now fervid nationalist searched for ways to remedy the defects of the union by strengthening the central government at the expense of the states. In New York, where he had married Elizabeth, the daughter of the prominent, well-connected General Philip Schuyler, in 1780, Hamilton advanced his career further by taking advantage of the new test laws which, by disbarring older Tory lawyers, enabled him to win quick admission to the legal profession. (12) Not yet thirty years of age, Hamilton had skillfully maneuvered himself into a position from which he might aspire to a leading role in the formation of a new nation.

Like his father-in-law, General Schuyler, he pressed for a constitutional convention to deal with the revenue problem, the threat of mutiny at Newburgh, and other emergencies which the loose Confederation simply could not handle. In particular, Schuyler insisted upon Congresss having control over interstate and foreign commerce, one of many centralist views which he shared with Hamilton; and in 1786 he used his considerable influence in the New York Senate to appoint Hamilton one of six commissioners to the Annapolis Convention where regulation of commerce among the states was to be discussed. As is well known, the Convention failed, but Hamilton, seeing in this confirmation of his belief that political unity was indispensable to commercial harmony, inveigled and manipulated the other delegates into signing a report which called for another meeting in Philadelphia the following spring to take into consideration the situation of the United States, to devise such further provisions as shall seem to them necessary to render the Constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union, and to report an act for that purpose to the United States and Congress assembled. (13) Just as he had done on several critical occasions earlier in his life, so he again orchestrated events his way. Hamilton was succeeding by one ingeniously calculated move after another in imposing his will on his newly adopted country, which must now be fitted to Hamiltons procrustean scheme for a highly centralized government.

The convention at Annapolis over, Hamilton returned to the New York assembly, where he held his seat with the powerful support of the business community. There he was the master strategist in committing the legislature, despite Governor George Clintons anti-Federalist opposition, to participation in the Philadelphia meeting. True to form, Hamilton managed to get himself appointed to the New York delegation as the sole Federalist. Clearly, though, much more work needed to be done in breaking down the resistance of Clinton and the radical localists who feared a strong national government. If the state laws disfranchising Tories could be repealed over the opposition of the anti-Federalists, these conservative men of property could be expected to vote for a more vigorous constitution to protect them against the states-rights radicals. So Hamilton, acting on these and purer motives of justice, spoke passionately for repeal. (14)

In Philadelphia the other New York delegates soon bolted the Convention, furious over what they believed to be the excesses of the Convention in drafting a new Constitution rather than amending the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton, for his part, thought the debates had not gone far enough in saving the nation from anarchy. He took a whole day to propose his own system of government which, while not ideal from his point of view-since the people, he believed, were agog with republicanism and incapable of political realism-came closest to the limited monarchy he secretly preferred. The chief executive and senators should hold office for life, subject only to good behavior. The president must have a veto over all Federal and state laws, he held, in order to balance a democratic lower house against the propertied interest of the senate. And, finally, governors of the states-mere administrative units in Hamiltons conception-should be appointed by the president, whose only check would be from congress and a Federal judiciary empowered to declare laws unconstitutional.(15)

The expected then happened. The proposal was voted down overwhelmingly, but Hamilton once again had shown his managerial skill with men. I revolutionized his mind, he said of one of them, Rufus King of Massachusetts, perhaps the most eloquent speaker in the assembly, who came over the Hamiltons position from the opposite side.(16) Hamilton always prided himself on having his way with people, as he had with Washington, Schuyler, King, and othersIn boldly arguing this scheme of government before the convention he was likewise trying to manipulate other highly influential men, national opinion-makers, into a favorable attitude towards what he considered a more realistic theory of federalism by offering a plan of government which he knew to be too advanced for them to accept. As a result, later on September 17, 1787, when the final draft of the proposed Constitution was ready for signing, many ideas which hitherto had been unpalatable to the delegates were in it-thanks to Hamiltons stratagem. After urging all of them to sign, or else face the dangers of anarchy and convulsion, Hamilton signed for New York, along with all but three of the 42 delegates. His own ideas were more remote from the plan than anyone else, he alleged, so imperfect was the Constitution, but in fact the new document incorporated many of Hamiltons ideas.

Hamilton had cajoled the Philadelphia assembly into drafting a new Constitution, but he must now turn to the more formidable problem of assuring its ratification in his own state. Robert Yates and John Lansing, anti-Federalists and Gov. Clintons men in the Constitutional Convention, had already returned to New York to prepare for the coming battle. Hamilton knew that the anti-Constitutionalists there were powerful and well-organized. He also realized that without New York, which by its strategic location held the country together, there was no hope for the United States as a great nation. The battle over New York loomed in Hamiltons mind as critical for world history. Was the United States of America, which promised so much, a true nation or only a congeries of states? At a deeper level, the struggle for ratification was critical for Hamiltons psychological and moral development. For at issue was his very manhood, his utopian attempt to organize reality as it ought to be, his transcending wayward naturein this case the unpredictable and quarrelling stateby imposing authority and order.

It was therefore no accident that his first articles defending the Constitution should appear in the New York Daily Advertiser under the name of Caesar. These polemical letters against Gov. George Clinton, the Cato of the piece, rehearsed the old problem of the republic vs. the consolidated state. Hamilton, however, seeing that his high-toned writing was not having its desired effect, soon wisely exchanged polemics for argument and began contributing more moderate articles under the vaguer name of Publius. These Federalist Papers (1788), some 77 essays in support of the proposed national government, authored by Hamilton with the help of James Madison and John Jay, proved much more effective not only with New Yorkers but with other Americans. Washington wrote that they had convinced him of the merits of the new charter, and even Hamiltons enemies grudgingly admitted the arguments were hard to refute.(17)

At the Poughkeepsie convention, held late that year to decide whether New York should ratify the Federal Constitution, Hamilton employed, the same arguments, down to their very phraseology, and capitalized on the more favorable public opinion on the Constitution that his writings had helped bring about. His manipulative skills were perhaps never better, and once again fortune herself seemed to conspire with his plans, for news of ratification of the Constitution by New Hampshire and Virginia in late June left New York no real alternative. Either she must come into the New Union, join Virginia, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and the other large states, or perish.

Alexander Hamilton had helped make a nation and now was bending it more and more to his will by defeating the strong, resisting forces of localism and tradition, as the victory in his home state demonstrated. Hamilton was Caesar, and the empire of his vision was the modern, totalitarian state. In these years Hamilton, not yet a Christian, saw no real choice between Caesar and Christ, nor could he as his only reality at this time seems to have been the political, the economic, the tangible. Men were not angels, he agreed with Madison, but his pessimism went much deeper, perhaps because of his Calvinist background. The effects of what he called the ordinary depravity of human nature were everywhere, of uncontrollable impulses of rage . . . . jealousy. . . . and other irregular and violent propensities.(18) There was yet no Christ in his thinking to redeem man, no supernatural virtue of love to overcome the war raging between man and man. Like Hobbes, whose view of human nature he shared, Hamilton saw the only hope for passion-driven man in the absolute security of the Leviathan state. Talk about the virtue of republics, with Montesquieu, Locke, and Jefferson, he believed, was not only idle and utopian but dangerous. There was no exemption from the imperfections, the weaknesses, and the evils incident to society in every shape. (19) Not the protection of their natural rights to life, liberty, and property, but the lust for power, was the motive of men in political associations. Hamilton neither signed nor approved of the Declaration of Independence.

This pessimism about man left to himself, this fear of mans arbitrariness, was what motivated Hamilton to seek more and more centralization of government so as to save men from themselves. In true Hobbesian fashion, he was prepared to choose security as against liberty if the choice must be made. But in Hamiltons mind, it was not really security but the general good that must be served. Interspersed among his writings, as Clinton Rossiter has shown, is this phrase and many other terms like the public safety, the public interest, and even the general will, all vaguely describing what he viewed as that transcending, ultimate end to which politics was only a means.(20) The very concept, Rousseauian in its nebulosity, shares with the ideas of the Frenchman and Hobbes too that utopian imprecision and casualness of languagethat sloganeering character which modern advertising and mind-control technology knows so well how to exploit. The first thing in all great operations of such a government as ours is to secure the opinion of the people, Hamilton wrote during the controversy over the Alien and Sedition Acts.(21) Public opinion was the governing principle of human affairs, and he had no doubt that it could be conditioned to accept the totalitarian state that alone could prevent the abuse of human liberty.(22)

For it was, in truth, mans liberty that made Hamilton, as a secular utopian, skeptical of the Articles of Confederation government and any other loose union. Decentralization allowed man too much scope for his native unruliness. If, as Hamilton believed, it is a maxim, that, in contriving any system of government, and fixing the several checks and controls of the constitution, every man ought to be supposed a knave, it followed that it is therefore a just political maxim, that every man must be supposed a knave.(23) How could men like Hamilton, men of stern virtue, the political elect who could neither be distressed nor won into a sacrifice of their dutyhow could they save other men from their own destructive, selfish passions except by rendering them impotent as moral agents before the ethical state, which, as Rousseau and later Hegel asserted, was freedom per se. Take mankind in general, he is reported to have said to the delegates at the Constitutional Convention.

They are vicious, their passions may be operated upon . . . . Take mankind as they are, and what are they governed by? Their passions. There may be in every government a few choice spirits, who may act from more worthy motives. One great error is that we suppose mankind more honest than they are. Our prevailing passions are ambition and interest; and it will ever be the duty of a wise government to avail itself of the passions, in order to make them subservient to the public good, for these ever induce us to action.(24)

And, he subsequently noted in the Federalist, mens passions could exploited for the public good by taking advantage of the fact that they generally did what they thought to be for their immediate benefit. Hence, the logic of Hamiltons fiscal program as Secretary of the Treasury when, in a series of reports on domestic and foreign debt, an excise tax, and a national bank he designed to align the selfish interest of the money, class with the new government. While he calculated, admittedly with little effort, to win over the masses of the people by advocating road-building and agricultural improvements. All this was consistent with essentially Hobbesian belief that men are rather reasoning reasonable animals and motivated by the pleasure principle.

Hamiltons assumption plan, by which the Federal government assumed the states unpaid debts, catered to the upper classes solely in order to transfer their loyalty from the state to the new central government. The means of doing this, as Madison, Rush, and others protested, was immoral, since the original owners of the securities had had to sell them at a great loss to speculators, who now stood to gain unconscionably.(25) But Hamilton was here, and in his other state papers, only concerned with the overriding principle of establishing the public credit of the new nation so that the central government would be strengthened, American natural resources developed, and a capitalist economy settled upon the land. His critics, he believed, had no theory, no general principles. Can that man be a systematic or able statesman who has none, he asked I believe not. No general principles will hardly work much better than erroneous ones. (26) Apparently, it meant little to Hamilton that Revolutionary War veterans, their widows and children, and other poor people would suffer from this political manipulation. But, then, Hamilton in his utopian scheme for a great Federal power was prepared to use immoral means, and, as pointed out above, he had never subscribed to the Declaration of Independence with its doctrine of the natural rights of the person.

Hamilton, unlike Jefferson, never seems to have understood the Western concept of the person and his inalienable rights. His reading, evidently, was confined to highly selective ancient and modern authors like Demosthenes, Cicero, Plutarch, Bacon, Montaigne, Machiavelli, and Rousseau.(27) In the company of the great majority of his American contemporaries, he knew next to nothing about the Middle Ages and its Christian teaching of the primacy of the person made in the image of God. He was acquainted with natural law, for it was of course an integral part of the 18th century world-view, but from Lockes Treatise of Government Hamilton seems to have drawn implications that led more to corporate idealism and collectivism of Rousseau than to the individualism of Jefferson. In any case, the Frenchmans concept of the general will rather than Lockes majority will was the fundamental tenet of Hamiltons political philosophy, at leasr before 1800. Accordingly, there was no place for minority rights, natural rights to life, liberty, and property in his ideal state which he tried to construct as secretary of the Treasury and adviser to Washington.(28)

Like Rousseau and all utopians, secular and religious, Hamilton justified coercion of the individualforcing him to be free, Rousseau called itin order to achieve the perfect society of his dream. Freedom was a great treasure, Hamilton agreed with the ideologues, propagandists, social engineers, and manipulators of all ages, but it must be organized against abuse. Unrestrained mans freedom degenerated into license and anarchy. Shall the general will prevail, or the will of a faction? Shall there be government or no government, was the way Hamilton put it in his Tully essays of 1794, written to prepare the people for the Federal governments military action against the Whiskey RebelsPennsylvania frontiersmen who opposed his excise taxwhich he was already planning.(29) And Hamilton himself in September of that year, fantasizing about military glory, rode out with a militia army of 12,000 men to force the Whiskey insurgents to be free!

Just as he morally never appreciated the persons infinite worth, viewing man with Calvin and Hobbes rather than Locke, so Hamilton could never advance in his social and political thinking to the concept of localism, better, of subsidiarity, as normative in mans relationship to other men. His twisted conception of human nature prevented him from seeing that Every agent is perfected by its own activity, which is the principle of subsidiarity. Society, he failed to see, exists only in and for its members. It has no higher unity under which the individual is subsumed, no ethical priority over its members. The common good, which Hamilton as a utopian confused with the totalitarian general will of Rousseau, and which he used force to impose on the backwoodsmen of western Pennsylvania, required that he place the good of the Whiskey insurgents before the collectivity of his ideal state. The common good also required that, as Madison proposed, the Federal government in its funding program discriminate between the original holders of certificates and speculators, but Hamilton himself would brook none of that. Like todays Marxists and other totalitarians, Hamilton did not realize that society, the state, or any organization exists for the good of the individual and not vice versa, that the communitys raison detat is to help man actualize the powers that God has given him.

Man, the principle of subsidiarity teaches, must be free to use his faculties, to act on his own initiative, employing his own means towards the end that he has chosen, without the regimentation of the state. This principle Hamilton rejected. He also violated the norm easily discoverable by reason, that the lower social unit, whether person, family, group, institution, or government has the right to exist and work out its rightful activities without the next superior unit interfering. As a social engineer who found man depraved and unpredictable, Hamilton committed the typical utopian error of liberating man from himself by trying to force him into static political and financial classes and structures which could then be absorbed by the total state into a transcendent unanimity. Not man, but his social relations preoccupied Hamilton: his thought was really more sociological than anthropological. Factionalism must be prevented, even if it meant the sacrifice of personal liberty. Ideological consensus in the perfected, universal state of Hamiltons conceit would make factionalism unnecessary, sinceif Marxist terms be permittedfactionalism was a kind of alienation which must disappear once men came to realize where their real interest lay and praxis was at last achieved.(30)

The Declaration of Independence, in its concern for the person and his natural rights, is of course antagonistic to these Hamiltonian ideas and draws from that Western tradition which Hamilton himself seems never to have understood nor, at any rate, thought worthy of preserving in the New World. The idea that mans soul is ultimately the only real value in humanity, an Augustinian insight which had deeply influenced Calvin and Hamiltons other spiritual forefathers, lies at the center of the Judeo-Christian tradition, but along with it and qualifying it is Aristotles and St. Thomass insistence that man is a social animal by nature. Jefferson in the Declaration clearly had exaggerated the one aspect of that tradition while slighting the other, that of the common good, and the fault runs through his thought in general. His extreme individualism, as we have seen in Chapter one, soon evolves into relativism and subjectivism, which are destructive of the common good. Jeffersons atomistic conception of society, moreover, can be traced directly to this reliance on Locke, Algernon Sidney, and other social contract thinkers. Hamilton, on the contrary, looked to the tradition of Hobbes and David Hume, both of whom held in the words of the latter that reason is and ought only to be the slave of the passions and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.(31) Neither reason nor natural lawmere hypotheses Hume called themwere present to guide man, according to this tradition. Government, the Declaration notwithstanding, is not based upon some fabled consent in the past, but upon accepted conventions. Its validity is not to be found in natural law and its self-evident truths of reason but in utility, There are, hence, no rationally discoverable absolute truths and values, according to Hume, to limit the modern state in its self-aggrandizement, and the way is opened to the absolutizing of the common good with Rousseau (the general will), Hegels deification of the state, and Hamiltons totalitarianism.

That Hamilton in his politically active years saw the only hope for man in the perfectly organized modern state, in Caesar rather than Christ, can also be seen in his doctrine of implied powers and his support of the Alien and Sedition laws of 1798. Both illustrate too his consistent adherence to the principles of Hobbes and Hume, which rejected the medieval, Judeo-Christian and classical view of mans inherent rationality and dignity.

The preamble of the Federal Constitution, lodging all power and initiative in the people, was enough to mar the charter in Hamiltons estimation; for how could the impure, the non-elect organize a true common-wealth. Hamiltons basic premise, we have noted, was that of all utopians, religious and secular: mans corrupted nature, issuing in license rather than freedom, must be restrained by government, which can only be organized by the elect. Only in this way could man be made to overcome his selfishness and live in the ideal society where his own good was transcended by the public good. To this end, the realization of the secular, where public virtue would replace private greed, the Federal government must have much more power than the Constitution provided. This meant, Hamilton knew, attacking the principle of subsidiarity wherever it could be found, but especially in the Constitution where the rights of persons and states were protected against the encroachment of the central government.

Exploiting, again, his special relationship to Washington, which allowed him to act the role of de facto premier in the national administration, Hamilton succeeded in 1792 in chartering a bank of the United States over Jeffersons objection that Congress was not authorized to do so. Jefferson and Madison also feared what they called the money despotism, the influence of that wealthy class whom Hamilton was courting in his fiscal program, and who posed a threat to the local sovereignty of the people. While Hamilton in his doctrine of implied powers argued that Congresss power to establish the bank was implied in the Constitution as a necessary means to the collection of taxes and regulation of trade, Jefferson and Madison defended the principle of subsidiarity here by pointing out that Hamiltons loose constructionist view of the Constitution could be reduced to the absurdity of saying that Congress had the total power to do whatever it thought good for the people of the United States.(32) Here, again, Jefferson and Madison spoke, albeit unwittingly, for Western, medieval Catholic tradition in citing the dangerous lack of intermediate structures between the people and the central government in Hamiltons program. But the ultranationalist prevailed, for Hamilton as a post-Reformation thinker knew next to nothing about the organic society of the Middle Ageswhich Edmund Burke at the time was trying desperately to recoverand the spirited Virginians were, in reality, powerless before the onslaught of the modern world.

Much more aware of the subtle, hierarchical, organic nature of true society, Jefferson and Madison were more likely to object to usury than Hamilton; and of course there are overtones of such an objection in their stand against Hamiltons plans for funding and establishing a national bank. They seem to have understood, as Aristotle and the Church fathers did before them, that usury exploits mans misfortune; that, from the point of view of the stateAristotle insistsusury leads to excessive wealth and materialism which prevent the citizen from engaging in the higher, fuller life of the intellect and spirit which is mans true end in the commonwealth.(33) Hence, Jeffersons well-known substitution in the Declaration of Independence of the phrase pursuit of happiness for property in the Lockean Life, Liberty, and Property, and his harking back to agrarianism vis-a-vis the modern capitalistic, industrial state of Hamilton. And, hence the efforts of the two libertarians to protect the natural and other rights of man against the national government in the Bill of Rights and in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions (1798), consistent with the principle of subsidiarity, which they wrote to protest the unconstitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Actslaws that did not go far enough, according to Hamilton, in curbing internal criticism of the Federal Administration.(34)

Hamiltons dependence upon legislation, so typical of the 18th century mentality, in the building of his nationalistic utopia appears, at first glance, to accord with the belief of the Founding Fathers in general that the best government is one of laws rather than men. But on closer study, what distinguishes Hamiltons legalism and rigid constitutionalism from the social and political thought of men like Jefferson, Madison, and especially Benjamin Rush and Charles Carroll of Carrollton, is the latters recognition in varying degrees that justice, and ultimately charity, alone binds the good society together. Hamiltons philosophy of man and society is mechanistic and cold, legalistic in the extreme. Man is considered as important in this perspective, but always as the fictitious man or political man of classical liberalism, never as man qua man. Otherwise, Hamilton would have appreciated the rise of society in mans nature, his family, and the extended family, the village; and he would have realized that the true state is one in which men cooperate in reason, and in its perfection, lovenot one in which they are forced to perform services for one another by a coercive, if well-meaning, government. Rule by law, in short, can be as tyrannous as government by men, if social charity does not prevail. Next best to love as the motive of society and the state, and included in it, is rational cooperation, which Plato and Aristotle as pre-Christian thinkers understood very well. Hamilton seems not to have perceived this. A striking contradiction in his basic premise is that of denying rationality and virtue to manmen are, reasoning rather than reasonable animalswhile attributing them to the ruling political and economic elites who in his ideal commonwealth prescribe the laws, economy, and mores of the state and are the state. This contradiction is of course glaring in socialism, capitalism, fascism, and all utopian systems which require pure elites for their operation. Politics and economics, despite Hamilton and so-called modern scientific thinkers, are moral sciences, since their ultimate concern is man, man who has a supernatural as well as a natural end.(35) Stateseven his beloved United Stateslaws, governments, economies, and banks exist. for man, not conversely. The Declaration of Independence is a testament to this truth. Hamilton, like so many of us, confused his means and ends.

Finally, in this analysis of Hamiltons thought, we should observe a paradoxical outcome of his labors as Americas apostle of ultra-nationalism and the corporate system. His motivation for the new nations economy was not moral but political, reminiscent of the old mercantilists and foreshadowing at the same time capitalistic and socialistic appropriation of government for their own economic purposes. It was false motivation, in principle, treating man as a means rather than an end; and while this politicized economy at first served Hamiltons centralistic purpose by wedding the money interest to the national state, it has led in our own day, of mass production and larger and larger corporations, to cartels and other international combinations which dominate states rather than serve them. The corporate system which Hamilton conceived as the handmaid of nationalism turned out to be, instead, the mistress of states. Corporate systems, with incomes greater than some modern states, are creating a new kind of internationalism. That is the paradox. Only the small entrepreneur and the small holder of property, marginal in Hamiltons theory of the state, remain in the low condition to which he relegated them and continue to decrease in number as huge, international corporations multiply. Special interests, not the common good, prevail and tyrannize over nations and their people.

Hamilton, weary and hard-pressedhe was only making $3500 a yearresigned from Washingtons cabinet in 1795, his fiscal program for the new nation established but still under attack from Jeffersonthat man of profound ambition and violent passionsand his followers.(36) Behind the scenes, however, he remained influential, advising the President on domestic and foreign affairs and even writing sections of Washingtons Farewell Address which committed the United States to Hamiltonian power politics abroad.(37) He was never to return to civil office, his aspiration to the presidency blocked by the Souths antagonism to his centralizing policies. Undoubtedly, in his own mind Hamilton rationalized this as a patriotic sacrifice of his greatest ambition for the good of the new Federal Union which Jefferson and the other Southern states-rights radicals were trying to destroy. Like other immigrants, then and now, he must prove his loyalty to the state at any priceeven of his life, as we shall see later. But Hamiltons motive here and in the fatal duel was ideological as well as psychological and sociological. As a member of the new elite of his utopian commonwealth he must prove himself innocent of self-interest and factionalism, an attitude that Thomas Molnar has shown to be typical of collectivistic-theorists from the Levellers to Rousseau and Marx.(38) In 1797 Hamilton publicly confessed to an intrigue with a married woman in order to clear himself of a charge of malfeasance as Secretary of the Treasury. The accusation was groundless, but, true to character, Hamilton sacrificed his private reputation rather than sully his honesty as a national leader.(39)

Hamiltons efforts to manipulate John Adams, once he had been elected to the highest office over his opposition, were rebuffed by Adams, who never forgave the younger man. Yet, as long as Washington lived an Aegis very essential to me, he admitted laterHamilton had a shield against him and others who resented his influence. It was Washington who obtained for his former aide-de-camp the rank of major general, second only to Washington himself in the provisional army raised in 1798 when war with the French seemed inevitable. So insistent was the ex-President on the choice of Hamilton, in fact, that he came close to resigning as commander-in-chief when Adams at first hesitated in favor of General Henry Knox. As it had happened before, when the scattered Whiskey insurrectionists failed to stand their ground against Hamiltons Federal troops and proved an empty threat to the national government, so the glory of leading a great army against the French in Louisiana and, perhaps, anti-Federalists in Virginia never materialized either. President Adams averted war with France by dramatically naming a new minister to negotiate with Tallyrand, who now promised to treat the American mission with respect. Hamilton was taken by surprise. He could neither use his army of young Federalists to seize Louisiana nor to punish Virginia and Kentucky for their resolutions against the Alien and Sedition laws.(40)

Had Hamilton been planning or considering a coup detat to save the United States from its internal as well as foreign enemies? He had threatened to deploy his private army, for that is how he thought of it, to subdue a refractory and powerful State, and he even mentioned chastening Virginia by name to one of his confederates. Jefferson may have seen through his plan when he asked:

Can such an army under Hamilton be disbanded? Even if a H. or Repre. can be got willing & wishing to disband them? I doubt it, & therefore rest my principal hope on their inability to raise anything but officers.(41)

We can only speculate on Hamiltons intentions, but there is no question that he was desperate and ready to employ any means to stop the anti-Federalists from coming to power. Earlier, in 1783, he had urged making use of the army at Newburgh for political purposes, and while Washington lived there was hope of Hamiltons realizing his American utopia by force of arms. Then, on December 14, 1799, Washington died suddenly. It was all over for Hamilton and his dreams of military glory. The great man removed from the national scene, Hamilton must now stand alone before his enemies, both among the moderate Federalist majority in Congress and the Jeffersonian Republicans who were beginning to sense victory in the upcoming presidential election of 1800. (42)

In the spring elections of 1800, to make matters worse, one of Hamiltons many enemies, Aaron Burr, swept his Republican candidates into office in New York City, defeating Hamiltons Federalist lackies and gaining control of the state legislature. Burrs victory in the key state of New York, Hamilton knew, meant that Burr and Jefferson would soon win the highest prize of allthe national government, which was essential to the completion of Hamiltons utopian scheme for the perfectly organized Leviathan state. Hamilton, driven to extremes, wrote to Governor John Jay of New York, a staunch Federalist, anglophile, and man after his own heart, suggesting extraordinary if not illegal moves to guarantee Public Safety by preventing Jefferson, an atheist in religion, and a fanatic in politics, from getting possession of the helm of state.(43) Jay would have no part of it. True, like Hamilton he had opposed the Declaration of Independence for fear of mob rule, and disliked Jefferson and his Jacobin friends, but he had already decided to retire from politics and was, anyway, too cautious a man to allow himself to be manipulated by Hamilton.

Thwarted in this resort to expediency, Hamilton turned his fury against John Adamsthat weak and perverse manwho had stripped Hamilton of his private army and dismissed his men in the cabinet. There was no place for Adamss vacillation, however disguised as moderation, in the executive of a great nation. Adams and Jefferson, Hamilton now maintained were equally bad, but, so deep was his enmity for Adams, that he would prefer Jefferson in the presidency! Hamiltons rationalization of this volte-face puts one in mind of his own precept that man is a reasoning rather than a reasonable animal:

If we must have an enemy at the head of the government, let it be one whom we can oppose, and for whom we are not responsible, who will not involve our party in the disgrace of his foolish and bad measures. Under Adams, as under Jefferson, the government will sink. The party in the hands of whose chief it shall sink will sink with it, and the advantage will be all on the side of his adversaries.(44)

The pure, the elect, the pro-Hamilton Federalists must either rule or wash their hands of all responsibility. It was all or nothing.

Hamilton decided to attack Adams himself in a pamphlet and to compare him in the most unfavorable light with Charles Pinckney of South Carolina, a good and innocent man who knew nothing of the intrigue. The aspersions on The Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq., President of the United States, which Hamilton signed, were intended for limited circulation among Federalist leaders who might be persuaded to drop Adams and line up behind Pinckney, Hamiltons candidate. Burr, however, had other ideas. He got hold of a copy of the pamphlet and had it printed in the Republican newspapers, embarrassing the Federalists by exposing their intraparty quarrels to friend and foe alike. Hamiltons stratagem was to no avail: Adams led the Federalist ticket with Pinckney as his running mate. As for the Republicans, Hamiltons fears were confirmed when Jefferson and Buff were named as standard-bearers. There seems to be too much probability that Jefferson or Burr will be President, he wrote to James Bayard. If Burr were the victor, Hamilton went on, he will certainly attempt to reform the government a la Bonaparte. He is as unprincipled and dangerous a man as any country can boastas true a Cataline as ever met in midnight conclave.(45)

This man Burr now began to appear to Hamilton as a greater rival than even Jefferson, perhaps because the two New Yorkers, were uncannily so much alike in character. Both were professed admirers of Caesarthe greatest man that ever livedand Napoleon (despite what Hamilton wrote to Bayard). Both were given to military fantasies and lusted after the presidency, which they saw as a powerful office from, which to indulge their dreams of glory and conquest and save a tottering nation. Each was a soldier of proven courage, restless for battle and ever watching for the decisive campaign, butunlike Washingtoneach mans character was flawed by an unsoldierly fondness for political and sexual intrigue and insubordination. As members of Washingtons staff during the Revolutionary War, the two young men did not escape the Generals reprimand which, however, Hamilton overcame with that happy combination of luck and manipulative skill which caused Washington to be his patron and Aegis until the very end. Hamilton, the intimate of Washington, rose to eminence as Secretary of the Treasury in the new nation, while Burrs career, lacking this high patronage, advanced less dramatically, with Hamilton keeping a close eye on the man whose path strangely was to cross his again and again over the next twenty years. Now, in 1800, in a rehearsal for their fatal duel on the Hudson, Hamilton and Burr stood face to face. At issue was not the senate, not a governorship as in the past, but the presidency itself, which each man in his utopian plan regarded as the key to total power.(46)

The Alien and Sedition Acts, higher taxes, and other major campaign issues all favored the Republicans in the presidential election, not to mention the disarray within the ranks of the Federalists occasioned by Hamiltons abuse of Adams. When the electoral votes were counted in February 1801, Jefferson and Burr led with 73 each. Accordingly, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives, where the Federalists had a majority, and where Hamilton believed that his influence, ever weakening, was still strong enough to declare Jefferson the winner. Cataline must be stopped, he pleaded with his fellow-Federalists. The public good must be paramount to every private consideration . . .(47) Burr, devoid of every principle, meant to turn the worst part of the community against the better part. Here, Burr, dangerously close to the office they both wanted, was the man of passion, driven by self-love, the man of Hobbes and Calvin against whom Hamilton had sought to organize the perfect state where true freedom not license should prevail. Here was this man about to lead the masses, the non-elect, into the nations governing circle.

Jefferson was elected president on the 36th ballot, not so much because of Hamiltons intervention as because Burr refused to make concessions to the Federalists. In Hamiltons view, the House had chosen the lesser evil, but with Jefferson President and Burr Vice-President there as hardly cause for celebration.

The year 1801 ended with greater tragedies for Hamilton. His eldest nineteen-year-old Philip, whom Hamilton looked upon as his successor, was killed in a duel in November with a New York City lawyer who had assailed Hamiltons policies in a recent speech. Never did see a man so completely overwhelmed with grief as Hamilton, a friend of many years remembered.(48) The scene I was present at when Mrs. Hamilton came to see her son on his deathbed (he died about a mile out of the city) and when she met her husband & son in one room beggars all description! (49) Hamilton was crushed. His eldest daughter, lovely Angelica, never recovered from her grief, and was considered insane the rest of her long life. And Mrs. Hamilton, who was later to lose her husband in the same way, barely held herself together.

Mrs. Hamilton, the little saint, was long known as a woman of deep religious faith. Despite many trials, some caused by Hamiltons womanizing, she had always remained loyal to her husband. Now, her husband, shaken as never before by this family catastrophe, seemed too to have glimpsed the absolute dependence of man on Gods will which his wife had always cherished and he himself had written about in a youthful description of the West Indian hurricane. What is become of thy arrogance and self-sufficiency? ... learn to know thy best support. Despise thyself and adore thy God. (50) Hamilton began studying the Bible, a son wrote years later, and also spent many hours perusing William Paleys Evidences of Christianity (1794). He led the family in prayer, and was observed by relatives and friends to be more loving and friendly than ever before.

Hamiltons earlier attitude towards religion had been merely exploitative. Religion was a thought-system, a socio-political concept rather than a personal relationship to God. It was a means for organizing the state of Hamiltons ideal conception, an ideological expedient for mobilizing public opinion against the French atheists. Jefferson and other American conspirators who planned to subvert the United States by promoting skepticism and disbelief. Religious ideas, he wrote in 1797 (note, the typical intellectualistic reference to religious ideas rather than beliefs), should be enlisted in the nations preparation for war with France.

It may be proper by some religious solemnity to impress seriously the minds of the people .... A politician will consider this as an important means of influencing opinion, and will think it a valuable resource in a contest with France to set the religious ideas of his countrymen in active competition with the atheistical tenets of their enemies. This is an advantage which we shall be very unskilled if we do not use to the utmost. And the impulse can not be too early given. I am persuaded a day of humiliation and prayer, beside being very proper, would be extremely useful .(51)

Hamiltons caesarism, his totalitarianism, had excluded Christ except as a servant of the state.

There were, of course, echoes of Hobbess Erastianism and contemporary continental Josephinism in this doctrine. And it smacks of that pragmatism, elaborated in the next century by William James and John Dewey, which as a variation of 18th century utilitarianism has become the American way of life. One is inclined to agree with Molnar and others that there is a type of American intellectual, more a creative organizer for power and a social engineer than a philosophical thinker pursuing knowledge and truth for their own sake.(52) In this phase of his life, Hamilton was an American intellectual par excellence.

Even as late as 1802, when his naive Enlightenment secularism was waning. Hamilton tried again to use religion to win over the American people to a defense of the Constitution. Jefferson and Burr were in office and Hamilton, knowing the formers strict constructionist view of the Constitution and states-rights philosophy and holding the latter in contempt, believed the nations charter to be in great danger. He had struggled for so long to perfect the Constitution, only now to see his doctrine of implied powers at the mercy of anti-Federalists. There was no way for him to know that Chief Justice John Marshall, appointed ironically, by weak and perverse John Adams the year before, would soon in Marbury v. Madison (1803) enunciate the doctrine of judicial supremacy and establish the power of the court by declaring an act of congress unconstitutional. Marshall would, in effect, achieve that centralization of power in an elite that Hamilton had failed to secure by force of arms. At any rate, Hamilton now outlined a plan for a Christian Constitutional Society, with chapters in each state, whose members would use all lawful means in concert to promote the election of fit men to public office, so that Jacobin enemies of Christianity and the constitution would never again hold high office in the nation.(53) Whether his motive here was as coarse as before, we cannot determine. But there a moderating provision in this scheme which was newexcept its harking back, in the best sense, to medieval social charityand one that perhaps shows that Hamiltons attitude towards Christianity was somewhat less exploitative than it had been. He now urged what he called a Christian welfare program in which vocational schools, academies, and other free institutions would help ensure the loyalties of the different classes of mechanics to the Hamiltonian state by preventing their being duped by foreign ideologists like Jefferson. The plan came to nought, but it demonstrates that Hamilton himself was still a secular ideologist, to some extent, in his reductionistic, socio-political conception of religion.

Hamilton in these years repeatedly spoke of retiring from the political scene and living the new life of religion that stirred within him. Yet, like Cincinnatus, he believed he must stand ready to draw his sword in defense of the nation he had founded. In the winter of 1804, Hamilton was alarmed by word that the man he had helped keep out of the White House was conspiring to dismember the Union. Burr, it was said, was seeking election as governor of New York so that he could deliver Hamiltons home state into the hands of a junto of New England secessionists led by Senator Timothy Pickering.(54) Pickering, a die-hard Federalist, had once been loyal to Hamiltons policy of radical nationalism, but disgruntled by Jeffersons acquisition of Louisiana and its implications for New England, he was sadly playing the traitor by intriguing with the American Cataline, who was using Pickering and other extremists for his own self-aggrandisment. The Hamiltonian state, the bullwark of order against mans depraved nature, was in the gravest jeopardy ever. Buff, to Hamilton, was the very personification of that danger, the man in whom all the evils of social and personal disorder seemed concentrated. Was he also, buried at some deeper level of unconscious, Hamiltons other self? And was the duel they would fight the ultimate encounter?

In the gubernatorial campaign that winter and spring, Hamilton lashed out against Burr on every occasion. The Albany Register and other newpapers printed letters in which Hamilton was reported to have denounced Burr as a dangerous man, and one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government.(55) They hinted too that Hamilton had hesitated to vent his despicable opinion of Burr in language even more vituperative. Burr decided to do nothing about these insults before election. Obviously, though, they must be answered in some way, as they were public accusations and, by the accepted code of honor at time, required Burr to take the initiative or be branded a coward.

The vote in April, overwhelmingly rejecting Burr, marked the end of his political career. There was still the matter of his honor. On June 18, Burr wrote a letter to Hamilton demanding a prompt and unqualified acknowledgment or denial of the use of any expressions like those which the newspaper reports attributed to Hamilton during the recent campaign.(56) This began the exchange of letters and representations through seconds which led to the duelor interview, as it was calledat Weehawken almost a month later.

Hamilton kept the duel a secret from Eliza. But one week before his death, he sat down at his desk and, holding back the tears, wrote a letter to be given to her in the event of his death:

This letter, my very dear Eliza, will not be delivered to you unless I shall first have terminated my earthly career, to begin, as I humbly hope, from redeeming grace and divine mercy, a happy immortality. If it had been possible for me to have avoided the interview, my love for you and my precious children would have been alone a decisive motive. But it was not possible, without sacrifices which would have rendered me unworthy of your esteem. I need not tell you of the pangs I feel from the idea of quitting you, and exposing you to the anguish which I know you would feel. Nor could I dwell on the topic lest it should unman me. The consolations of Religion, my beloved, can alone support you; and these you have a right to enjoy. Fly to the bosom of your God and be comforted. With my last idea I shall cherish the sweet hope of meeting you in a better world. Adieu best of wivesbest of women. Embrace all my darling children for me.(57)

And the night before the duel Hamilton seems to have turned as a matter of course to Theodore Sedgwick, an old friend and anti-Burrite, to explainas he could not to his wifewhy he must risk his life, even die if necessary, to stop Burr and the other secessionists from destroying the Hamiltonian empire. I will here express but one sentiment, he condensed his political philosophy into one final testament, which is, that dismemberment of our empire will be a clear sacrifice of great positive advantages without any counter-balancing good, administering no relief to our real disease, which is democracy, the poison of which, by a subdivision, will only be the more concentrated in each part, and consequently the more virulent.(58)

The dilemma for Hamilton was a new one and the most formidable of his life. He must meet Burr, pistol in hand, on the heights of Weehawken, or appear to the world not only cowardly but unworthy of the moral leadership of the great empire which was his creation. Yet, as a serious Christian, he must not kill. This dilemma of choosing between Caesar and Christ in the most personal, existential sense could be resolved in only one way. In his final letter to Eliza, written at 10:00 P.M. the eve of the fatal interview, Hamilton described what he would do:

The scruples of a Christian have determined me to expose my own life to any extent rather than subject myself to the guilt of taking the life of another. This much increases my hazards, and redoubles my pangs for you. But you had rather I should die innocent than live guilty. Heaven can preserve me, and I humbly hope will; but in the contrary event I charge you to remember that you are a Christian. Gods will be done! The will of a merciful God must be good.(59)

Then, in a tender gesture of love for his dead son, Philip, and all his children, Hamilton lay down next to twelve-year-old John and recited with him the Lords prayer.

The next morning, July 11, 1804, Hamilton was mortally wounded by Aaron Burr as they faced each othernationalist and disunionistfor the last time on the banks of the Hudson. The evil passions of man, which Hamilton had sought futilely to transcend mechanically in some visionary social and political system, were now overcome and transcended spiritually in Hamilton himself by an act of love for his fellow man in Christ. As he had said he would, in his letter to Eliza and in a memorandum discovered after his death, Hamilton had reserved and thrown away his first fire, even his second.

As he lay dying in the bosom of his loving family, one thing alone remained for Hamilton. He sent for Bishop Richard Moore, Episcopalian bishop of New York, and begged to be united to the church by receiving Holy Communion. Do you sincerely repent of your sins past? Have you a lively faith in Gods mercy through Christ, with a thankful remembrance of the death of Christ? And are you disposed to live in love and, charity with all men? Yes, yes, yes. I have no ill-will against Colonel Burr. I met him with a fixed resolution to do him no harm. I forgive all that happened.(60)

ENDNOTES

- Quoted in Nathan Schachner, Alexander Hamilton

(New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, Inc., 1946), p. 25. Back

to text.

- Ibid., p. 23. Back

to text.

- Ibid., pp 1-15; Harold C. Syrett

and Jean G. Cooke, ed., Interview in Weehawken: The Burr-Hamilton Duel As Told

in the Original Documents, Introduction and Conclusion by Willard M. Wallace (Middletown,

Conn.. Wesleyan University Press, 1960), p. 164. Insightful on Hamiltons religious

development is Douglass Adair and Marvin Harvey, Was Alexander Hamilton a Christian

Statesman, originally published in the William & Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series,

XII (April 1955) and reprinted in Jacob E. Cooke, ed., Alexander Hamilton; A Profile

(New York: Hill and Wang, 1967), pp. 230-255. Back to text.

- Schachner, pp. 7. 18. 20. Back

to text.

- Quoted in ibid., p. 19. Back

to text.

- Ibid., P. 31. Back

to text.

- Ibid., p. 34, 39-40; Charles

H. Metzger, S.J., Catholics and the American Revolution: A Study in Religious

Climate (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1962). Back to text.

- Quoted in Schachner, p. 19. Back

to text.

- Ibid., P. 45. Back

to text.

- Ibid., pp. 56, 10. Back

to text.

- Allan Nevins, Alexander Hamilton,

in the Dictionary of American Biography: Broadus Mitchell, The Continentalist,

in Cooke, p. 41. Back to text.

- Schachner,

pp. 144-146; Mitchell, p. 46; John A. Krout, Philip Schuyler, in the Dictionary

of American Biography. Back to text.

- Quoted

in Schachner, pp. 190, 187. Back to text.

- Ibid.,

pp. 190, 194. It is interesting to compare the two men in their social and political

orientations. Hamilton, an immigrant, wanted to be one of the better sort, as

the upper-class was called in early America. He wanted to be at the top of the

deferential society and be a leader in the politics of status. Clinton, the son

of an Irish immigrant, worked to replace the politics of status with one of multiple

interests. See E. Wilder Spaulding. His Excellency George Clinton (1938) and William

Chambers George Clinton in John A. Garraty, ed Encyclopedia of American Biography

(New York: Harper & Row. Pub.,1974) Back to text.

- Schachner,

p.196; Mitchell, p.49. Back to text.

- Schachner,

p. 196. Back to text.

- CIaude

G. Bowers. Hamilton: A Portrait, in Cooke, p. 19; Schachner, pp.208, 211-214.

See C.Edward Merriam, A History of American Political Theories (New York: The

Macmillan Co., 1903), pp.100-122. For Clintons Cato Letters, see Cecelia M.

Kenyon, ed., The Antifederalists (Indiaanapolis: Bobbs_Merrill Co. Inc., 1966),pp.

301-322. Bobbs-Merrill Co., Inc. Back to text.

- Quoted

in Adrienne Koch, Hamilton and Power, in Cooke, P. 17. Also see idem., Power

Morals and the Founding Fathers; Essays in the Interpretation of the American

Enlightenment (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1963), ch. iv., pp.

50-80. Cf-The Federalist No. 15 in Milton Cantor, ed., Hamilton (Prentice-Hall,

1971), pp. 51-53. Back to text.

- Quoted

in Koch, Hamilton and Power, p. 217. Back to text.

- Clinton Rossiter, Hamiltons Political Science,

Cooke, pp. 207-208. Back to text.

- Quoted

in ibid., 213; Thomas Molnar, Utopia: The Perennial Heresy (New York: Sheed and

Ward, 1967), p. 10; Cecelia M. Kenyon, Alexander Hamilton: Rousseau of the Right,

Cooke, pp. 166-184. Back to text.

- Quoted

in Rossiter, p. 213. Back to text.

- Ibid.,

198. Back to text.

- Quoted

in in Kenyon, p.173. Back to text.

- Ibid.,

pp. 175-182. Back to text.

- Hamilton

to James A. Bayard, January 16, 1801, Henry Cabot Lodge, ed.,The Works of Alexander

Hamilton (New York, 1904), X, p. 415.

Back to text. - Rossiter, p. 189. Back to

text.

- Kenyon, p.183. Miss Kenyons essay

is perceptive, but her understanding of the Middle Ages, whose social and political

philosophy she likens to that of Hamilton, (pp. 178-179), is superficial. Back

to text.

- Quoted in Schachner, p. 335;

Molnar, Utopia, p. 7. Back to text.

- Cf.

Subsidiarity in Walter Brugger, ed., Philosophical Dictionary, trans. Kenneth

Baker (Spokane, Washington: Gonzaga University Press, 1972), pp. 397-398; Molnar,

p. 139; Jacob E. Cooke, The Reports of Alexander Hamilton, in Cooke, p. 74;

Thomas Molnar, The Decline of the Intellectual (New Rochelle, New York: Arlington

House, 1961), pp. 334-338. Back to text.

- Quoted

in George H. Sabine, A History of Political Theory (3rd. ed.; New York; Holt,

Rinehart and Winston, 1966), p. 600; Molnar, Utopia, p. 167; Rossiter, p. 187.

Back to text.

- Sabine,

pp. 603-605; Molnar, Utopia, p. 7; Koch, Power, Morals, and the Founding Fathers,

p. 112. Back to text.

- For

an excellent discussion of usury, subsidiarity, and other social principles, see

Cletus Dirksen C.P.P.S., Catholic Social Principles (St. Louis Mo., B. Herder

Book Co., 196 1), p. 186 et passim. Back to text.

- Koch,

Hamilton and Power, p. 222; Nevins, Alexander Hamilton. Back

to text.

- Dirksen, pp. 64-65; Molnar,

Decline of the Intellectual, p. 349 Back to text.

- Nevins,

Alexander Hamilton, Dirkson, p. 214. John C. Miller deals with the paradoxical

nature of Hamiltons career in his Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox (New

York, 1959) Back to text.

- Felix

Gilbert, Hamilton and the Farewell Address,' Cooke, p.116 Back

to text.

- Decline of the Intellectual,

p.333; Kenyon. p.179 Back to text.

- Nevins,

Alexander Hamilton. Back to text.

- On

Washington as Hamiltons Aegis, Koch, Hamilton and Power, p.224; Schachner,

pp. 386-387; Nevins, Alexander Hamilton. Back to text.

- Quoted in Schachner, pp. 386, 387. Back

to text.

- Koch, Hamilton and power,

pp. 220-226. Back to text.

- Quoted

in Adair and Harvey, Cooke, p. 245; Samuel Flagg Bemis, John Jay, Dictionary

Of American Biography Back to text.

- Quoted

in Schachner, p. 394. For Hamiltons characterization of Adams see Adair and Harvey,

p. 243. Back to text.

- Quoted

in Schachner, pp. 396-397. Back to text.

- Quoted

in Koch, Hamilton and Power p. 223; Willard M. Wallaces Introduction to Syrett

and Cooke, Interview in Weehawken, pp. 3-35; Marcus Cunliffe, Aaron Burr, in

The Encyclopedia of American Biography. For a less unprejudiced comparison of

the two men, see Allan McLane Hamilton, The Intimate Life Of Alexander Hamilton

(New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1911) et passim. Back to

text.

- Quoted in Syrett and Cooke, p.

29; John C. Miller, The Federalist Era 1789-1801 (New York: Harper & Row, Pub.,

1963), ch. xiv, pp. 251-277. Back to text.

- Quoted

in Schachner, p. 408; Miller, The Federalist Era, p. 272. Back

to text.

- Quoted in Schachner, p. 408.

Back to text.

- Ibid.,

pp. 25, 108; Hamilton, The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton p.109. Back

to text.

- Hamilton to William L. Smith,

April 10, 1797, William L. Smith Papers, Library of Congress, quoted by Adair

and Harvey p 240n ibid, p. 248; Molnar, Decline of the Intellectual, p. 336. Back

to text.

- Ibid., ch. ix, pp. 260-288;

Sabine A History of Political Theory, pp.303, 372 Back to text.

- Schachner, p. 412. Back to

text.

- Adair and Harvey, p. 252. 55 Back

to text.

- Quoted in Schachner , p.422;

Hamilton, The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton, p.390 Back

to text.

- Quoted in Schachner, p. 423.

Back to text.

- Quoted

in Hamilton, The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton, pp. 393-394. Back

to text.

- Quoted in Schachner, p. 427.

Back to text.

- Quoted

in Hamilton, The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton, pp. 394-395. Back

to text.

- Ibid., p. 406n. Back to text.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

DElia, Donald J. Alexander Hamilton: From Caesar to Christ. Chap. 6 in The Spirits of 76 (Front Royal, VA: Christendom College Press, 1983), 87-114.

Reprinted with permission of Christendom College Press and Don DElia. All rights reserved.

The Author

Donald J D'Elia was professor of history at The State University of New York at New Paltz. The author and co-author of many books on American history, Dr. D'Elia's Dr. Benjamin Rush: Philosopher of the American Revolution, published by the American Philosophical Society in 1974, is a standard in the field of American Revolution scholarship. The book was described as "magnificent" in the Journal of the American Medical Association and was cited for its importance by the Institute for Early American History and Culture in its "Bicentennial Bibliography of the American Revolution" (1976). The Library of the History of Ideas has selected his work as among the "best of the essays on the American Enlightenment" to have appeared in the prestigious Journal of the History of Ideas. He is the author of The Catholic As Historian, and Spirits Of '76: Catholic Inquiry among other works.

Dr. D'Elia was cited by Governor Mario Cuomo in 1984, for his "many years of dedicated service to the humanities." He is listed in Marquis "Who's Who in America" (East), "Who's Who Among Italian Americans," "American Catholic Who's Who," and other reference works. Don D'Elia was active with the Society of Catholic Social Scientists and was a member of the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Copyright © 1983 Christendom College Press