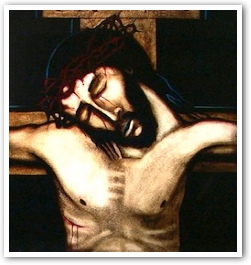

Lent: A Call to Purification

- FR. LEONARD M. PUECH

Lent is the annual call to purify our souls for the great feast of Easter, figure of the eternal Easter, for which the soul must be perfectly pure.

|

Spiritual authors divide the ascent of the soul to God into three states: the purgative way, the illuminative way, and the unitive way. In the purgative way, which comes first, the chief aim is to purify the soul, so that it can be enlightened and finally reach perfect union with God. These three ways are often presented as three successive stages in the spiritual ascension: one begins in the purgative, leaves it to enter into the illuminative, from which it passes to the unitive way.

This way of presenting purification, illumination and union, as successive stages is legitimate inasmuch as, at different ages in the spiritual life, one or the other of the three tends to predominate. But in reality they are three different but simultaneous processes, which continue through all the ages of the spiritual life. In the measure that the soul is purified, it is enlightened and united to God, so that perfect purification is reached at the same time as perfect union. Nevertheless there is an order between this threefold action: the affections of the soul must be purified before the mind can receive the divine light, and we must know God before we can love him or unite our will to his, so as to be one with him. Purification is, therefore, the first step in the spiritual life; it is not only for beginners, but necessary for all of us.

This necessary purification is threefold: purification from mortal sin, purification from venial sin, and purification from natural motives.

Of course, the first step for anyone who wants to draw near to God, is to turn away from mortal sin, from grave disobedience to the Father. No one may pretend to love God or claim his favor, if he does not regret having rebelled against his will or if he refuses to do it. Turning away from mortal sin means that we recognize we were very disobedient to the Father, that we regret it, either on account of the punishment deserved or of the harm it did to our soul, or better, because we offended a Father so infinitely good and great. If we truly regret, we will also be firmly determined not to do the same thing again and to do something special to make up for the offence.

Great as the regret may be, it is not enough to be forgiven, because only the one offended can forgive, and as long as he does not, one is not forgiven. God never refuses to forgive the one who sincerely regrets his wrongs, as men do, at times; but even with him it is necessary to ask to be forgiven. Although Judas regretted his treason and even tried to annul it by bringing back the price of his betrayal, he was not forgiven because he did not ask for forgiveness. Had he asked, he would have been forgiven; but he was too proud to ask.

We cannot ask God himself to forgive us, because he entrusted all forgiveness to Jesus: "The Father does not judge any man, but all judgment he has given to the Son, that all men may honor the Son even as they honor the Father" (Jo. 5,22-23). It would be vain to try to confess directly to God. He would be offended because, "He who does not honor the Son, does not honor the Father, who sent him" (Jo. 5,23).

But neither can we go directly to Jesus to be forgiven, since he appointed the Apostles to continue his mission, especially his mission of forgiveness, in one of the apparitions after the Resurrection: "Peace be to you! As the Father has sent me, I also sent you." When he had said this, he breathed upon them, and said to them: "Receive the Holy Spirit; whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven; and whose sins you shall retain, they are retained" (Jo. 20,22-23). Because the mission of the Apostles was to continue "even to the consummation of the world" (Mt. 28,20), they appointed successors to carry on this mission of forgiveness.

This, then, is the reason why one must have recourse to the sacrament of Penance to obtain forgiveness, and also the reason why the Church has made it a law to receive it at least once a year. If, however, reception were impossible, at least immediately, and one would sincerely regret his sins with the firm intention to receive the sacrament, his sins would be forgiven, but the obligation would remain to confess them, for confession is necessary in order to receive sacrament. The necessity of receiving the sacrament to be forgiven and the necessity of confessing one's sins to receive the sacrament are two different things. Although the Council of Trent defined as an article of faith the necessity of both, some people don't seem to be aware of it, when they advocate collective absolution without confession.

Confession is so necessary for the reception of the sacrament that, when collective absolution is allowed, in some urgent cases, those who receive it must not only regret their sins, but also intend to confess them later on, even if already forgiven; and, if they participated in a collective celebration of Penance in order to avoid confession, the absolution would be invalid for them, and their sins would not be forgiven. The same conditions are required for the validity of the absolution given to an unconscious person: contrition and the desire to receive the sacrament and to confess; the obligation remains to accuse the sins thus forgiven, if the person recovers.

What makes confession so necessary for the reception of the sacrament of Penance is the mission entrusted by Jesus to the Apostles. He did not give them the power to forgive sins indiscriminately: "Whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven them; and whose sins you shall retain, they are retained" (Jo. 20,23).

How could it be otherwise? God himself does not always forgive and he cannot, unless we regret having offended him. The priest, therefore, must judge, whether he can forgive or must refuse pardon; and he cannot make that judgement unless he knows what sins were committed and what the disposition of the penitent is. Because he cannot read as Jesus could the conscience and the heart of the penitent, he has no other means of knowing, apart from his confession.

In the administration of Penance the priest, apart from his duty to God not to forgive when God does not forgive, has also a duty to the Church, whom he represents. Saint Paul reminds the Corinthians of their obligation "not to associate with one who is called a brother if he is immoral, or covetous, or an idolater, or evil-tongued, or a drunkard, or greedy... Expel the wicked man from your midst" (I Cor. 5,11,13). Because, as he repeats, "a bit of leaven corrupts all the dough" (Cor. 5,6; Gal 5,9). The priest, therefore, cannot give wholesale absolutions and admit everybody to Communion without knowing from personal confession whether they may be allowed to receive or not. This is why the decree on the new rite of Penance states very clearly: "Individual, integral confession and absolution remain the only ordinary way for the faithful to reconcile themselves with God and the Church unless physical or moral impossibility excuses from this kind of confession" (N. 31).

So, when so-called liturgical experts tell us that the ideal and normal way of reconciliation should be collective absolution, they not only contradict directly this decree, but they reject implicitly the definitions of the Council of Trent on the necessity of confession.

Let us therefore realize that the first step in the spiritual life, the first and necessary means of purification is a humble and sincere confession of all serious sins, inspired by a sincere regret and accompanied by a firm resolution to avoid them, to keep away from the occasions of sin and to make reparation of the offense to God, and of the harm done to others through injustice or scandal.

To keep away from confession because it is hard, means to deprive oneself of God's mercy; to remain in a constant danger of eternal damnation; to lose all the merit of all that one does or suffers, and all the graces one could draw from the sacraments; to deprive oneself of the deep peace coming from a good confession; trying perhaps to find it instead through a psychologist, who will demand not only one, but, many and much more detailed confessions, and charge a stiff fee for very uncertain results.

Because too many neglect this wonderful offer of forgiveness, which is the sacrament of Penance, and might live in the state of mortal sin for months and even years and lead a life barren of all merit, the Church made it a law for all Catholics to go to confession at least once a year at Eastertime. Let us heed this invitation to purify our souls by a sincere confession.

Receiving the sacrament of Penance is useful, even if someone does not have any serious sin, for it is not enough to purify the soul from mortal sin. It must be cleansed even of venial sin.

Too many people are content with avoiding mortal sin and are not even aware of the many venial sins they commit. Otherwise, how could they come to confession after six months, a year, or even more, and tell their confessor: "I don't have any sins"? Once in a while it is even impossible to bring a person to mention one single sin, in order to give absolution. Yet St. John declares, "If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us" (Jo. 1,8).

That good Christians may live for months, or even years, with the help of God's grace, without one single serious sin is not difficult to believe. But to suppose they could live such a long time without one venial sin seems quite incredible: it would require very special graces and an extraordinary fidelity to grace, such as we see in the saints.

Because saints are not all that common, it is much much more probable that many good people, while they avoid serious sin, do not attach any great importance to these minor faults, which they commit as naturally as they breathe and forget just as easily.

Perhaps some are ignorant and don't know these faults are sins, like the man who having emptied quite a bag of serious sins, was asked if he had committed any sins against charity. "Oh, no, Father; I mind my own business," he said.

"You never get impatient, never talk about the faults of others, never swear at them?"

"Oh, yes; but that's not a sin!" he said.

True, many actions are not mortal sins, but nevertheless they are sinful, and not just imperfect. It is the same with human love: many actions may not destroy friendship and yet they cool it, because they offend and displease. Perfect friendship requires that anything which offends or displeases even lightly be avoided. To do anything against the will of a friend is bound to displease him. This is exactly what venial sins do. They are not a complete rebellion against God's will, as mortal sin is; so the divine friendship is not broken. They are like the little disobediences of a child, who loves his father and wants to obey him, but at times finds it difficult and is carried away by some strong desire or aversion and does what his father has forbidden, or omits what he has commanded.

How many of these small disobediences to our heavenly Father we find in our lives, when we examine them more closely! How often we fail to love our neighbor as he has commanded us to! It is so easy to sin against charity, through words or through silence, by action or an attitude, by impatience or by coldness and indifference.

So many fail to realize that when they talk about other people's faults, even if it is without malice, they sin against charity, because they are doing to others what they don't want done to themselves. They are so little aware of it that they insist they never talk about others, as if they were saints St. James after all, affirms: "If anyone does not offend in word, he is a perfect man" (James 3,2).

More numerous, perhaps, are those who pay no attention to the unkind thoughts or feelings they keep wilfully, assuming they are not a sin as long as they are not manifested, as if sin were not committed in the heart and as if God did not see the heart. Who accuses these thoughts and feelings before they reach the degree of hate?

Apart from these light failings against charity, how often we commit all kinds of little faults! It may be pride bragging and boasting, trying to show off, thinking oneself so much superior to others. It may be vanity an excessive care about looks, dress, desire for admiration. It may be gluttony little excesses in food or drink, either by taking too much or being too choosy. It may be too much curiosity about people or about news or for an unnecessary knowledge. It may be idle words, light indiscretions or imprudent looks or imaginations. It may be laziness, idleness, waste of time, some neglect of duty. One may be too free or too tight with money.

There is no end to the many ways in which one may commit venial sins. They are like germs you cannot count them, and they multiply as easily. Like germs, one does not kill, nor do a few; but as they multiply they weaken the soul and its resistance to mortal sin. Like the germs they are so small that we don't see them and therefore do nothing to avoid them.

This is why frequent confession may be very useful to purify the soul from venial sin. To be done properly, it must be preceded by a serious examination of conscience, which will reveal the faults committed, and should be accompanied by a firm resolution to do something to avoid them. If it is frequent enough, it will be possible to remember even small failings, and the resolution being renewed often won't be forgotten and will have a chance to bring results.

In his encyclical on the Mystical Body of Christ, Pius XII, while protesting against some opinions aimed at turning the faithful away from frequent confession, describes its advantages: "Although there be different means, all praiseworthy, to wash away venial sins, we wish to recommend highly the pious practice of frequent confession, introduced into the Church by an inspiration of the Holy Spirit. It increases knowledge of self, fosters Christian humility, tends to uproot bad habits, opposes spiritual negligence and tepidity, purifies the conscience, fortifies the will, lends itself to spiritual direction, and through the sacrament increases grace. Let those who lower frequent confession in the esteem of the younger clergy know that they are doing something contrary to the Spirit of Christ and very harmful to the Mystical Body of our Savior."

When a priest, as sometimes happens, discourages penitents from frequent confession of venial sins, he goes against the mind of the Church and the practice of the saints. For the Code of Canon Law proposes weekly confession for all religious, and grants special privileges for the gaining of plenary indulgences to all pious souls who go to confession habitually twice a month.

The saints practised frequent confession: some every day (St. Catherine of Siena, St. Bridget of Sweden, St. Coletta, St. Charles Borromeo, St. Ignatius and others); some twice a day (St. Ignatius in the latter part of his life, St. Francis Borgia and St. Leonard of Port-Maurice). They recommended frequent confession. St. Leonard proposed daily confession to the priests who accompanied him on his preaching of missions: and he exhorted sisters to go to confession as often as they were allowed. St. Alphonsus gave them the rule that they should confess twice a week, and every time they committed a deliberate sin. St. Francis de Sales prescribed the same for his nuns of the Visitation, and for devout souls in the world, once a week and if possible before Communion.

This was possible in those days, when there were many more priests. Today it would be impossible most of the time, but at least we should avail ourselves of the opportunity to purify our souls from venial sin when it is offered to us, and priests should not refuse to hear these confessions of devotion and much less turn the faithful away from them.

Of course, for frequent confession to be fruitful, it must not be just routine. One must confess something definite, regret it, and be firmly resolved to do something definite about it. Because of this strict vigilance on one's actions, and these frequently renewed resolutions, one may be able, with the help of God's grace, to avoid, as the saints did, all fully voluntary or deliberate venial sins, since a vow to avoid them is lawful, and if one is committed, it will be rejected without delay.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Fr. Leonard M. Puech, O.F.M. "Lent: A Call to Purification." In Spiritual Guidance (Vancouver, B.C.: Vancouver Foundation of Art, Justice and Liberty, 1983), 227-232.

Republished with permission of the Vancouver Foundation of art, Justice and Liberty.

The Author

The late Fr. Leonard M. Puech wrote a popular column for the B.C. Catholic from 1976 to 1982. Those columns were compiled and published by the Vancouver Foundation of Art, Justice, and Liberty as the book Spiritual Guidance in 1983. The VFAJL is interested in reprinting Spiritual Guidance. Anyone who would like to contribute to this worthy cause please write: Dr. Margherita Oberti, 1170 Eyremount Drive, West Vancouver, B.C. V7S 2C5.

Copyright © 1983 Fr. Leonard M. Puech