Fidelity

- DONALD DEMARCO

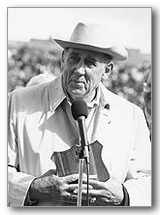

The son of Lithuanian immigrants, Edward Krauciunas grew up in the Back of the Yards section of Chicago, which was well known for it knockdown-dragout toughness.

|

Edward Krauciunas

|

When he passed through the three ethnic districts that lined the route to his violin lessons, the Irish, Italians, and Poles took turns assaulting him, both on his way there and on his return home. He never succeeded in mastering the violin, but he did become an adept boxer.[1]

His father worked as a butcher and kept Doberman pinschers around to discourage would-be robbers. The family income was never sufficient to create the hope that Edward could ever leave his section of Hogtown to pursue a better life. College was simply unaffordable and, therefore, out of the question.

While playing football for De La Salle Institute, however, he impressed his high-school coach, Norman Barry. It was Barry who, because he had trouble pronouncing Krauciunas, shortened his name to "Krause" and, for good measure, supplied the enduring nickname of "Moose".[2] Barry had played on Notre Dames undefeated National Championship team in 1920 and was the backfield running-mate of the legendary George Gipp. He took his protegé to South Bend, Indiana, one weekend and gave him a chance to display his gridiron prowess before the critical eye of his former coach, Knute Rockne.

Rockne liked what he saw and gave Moose Krause an athletic scholarship to Notre Dame.[3] In retrospect, it may have been the soundest investment the university ever made. Moose went on to become an All-American tackle in 1932 and 1933, on both offense and defense. He also was an All-American center in basketball in the three years from 1932 to 1934. He graduated cum laude with a degree in journalism. After graduation, he coached the universitys basketball team for eight seasons. He distinguished himself as "Mr. Notre Dame" during his long tenure — from 1949 to 1981 — as the schools athletic director. Though he is one of many Notre Dame alumni to have been inducted into the Football Hall of Fame, he is its only alumnus to have been enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame.

In 1967, shortly after returning from Rome, where Edward Krause, Jr., was ordained a priest in the Holy Cross Order, tragedy struck. Mooses wife, Elise, was seriously injured when a young man, driving under the influence of alcohol, ran a stop sign and rammed the rear of her taxi. She suffered severe damage to two regions of the brain, one affecting memory and the other, emotional control. Doctors did not expect her to survive the night. Moose, however, repeatedly expressed his certainty that his wife would not die.

She indeed survived, living for an additional twenty-three years. She was in intensive care for four months, came home for a long period of convalescence, and spent her last eight years in a nursing home. During this final period, Moose visited her at least twice a day, spoon-feeding her when she could not feed herself and singing to her when she was no longer able to speak. They celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary in the nursing home. Moose donned a white tuxedo, and he and his wife renewed their marriage vows.

It was Mooses uncomplaining fidelity and devotion to his wife that prompted Notre Dame President Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C., to say to Edward, Jr.: "Your father has had many public successes in life, but nothing is more important in Gods eyes than how he cared for your mother for all those years."[4]

Moose Krause was a giant and a legend who had distinguished himself in a sport where giants were commonplace and at a school where legends were customary. Yet these marks of distinction, extraordinary as they are, take a distant second place when compared with the fidelity he showed to his wife, Elise. The world was familiar with his media image, but those close to him saw something far more impressive. In the words of another Notre Dame immortal, former head football coach Ara Parseghian:

His dedication to his faith and to his marriage vows are to be admired and emulated. No one could have been more devoted to his wife than Ed was in the long years after an unfortunate automobile accident robbed her of a normal life. In those years, Moose was able to serve his wife and able to fulfill all her needs. There was no better demonstration of great devotion to family and his religion.[5]

Moose never lacked for opportunities or inducements to enjoy a broader social life than what his wifes nursing home could offer. When he kept turning down requests to travel with the team or to go off on golf holidays, he wondered if people sometimes felt sorry for him. To his son, Edward, Jr., he once said: "Its my responsibility to take care of your mother — theres nowhere Id rather be than in the room with your mother."[6]

Fidelity is a more immediate expression

of love than the desire for happiness.[7] This is something that was known to

our primal parents. Eves sin occurred prior to Adams. During that

interim between sins, Adam may very well have felt that it was better to accompany

his wife east of Eden than to remain in Paradise without her. The desire to be

with the one whom one loves is more urgent and demanding than the desire for ones

own happiness. Far from feeling sorry for Moose, those who knew him well both

admired and envied him.

Commentary

Fidelity is the virtue that allows us to persevere in living out an unswerving commitment. This pledge of fidelity may take place on any of three distinct levels. We can speak of a commitment to a task, to an ideal such as justice, truth, or beauty, and to another person, as epitomized by Moose Krause in the way he lived out his marriage to his wife, Elise.

Contemporary society offers three major objections to practicing this virtue. First, it regards fidelity as incompatible with freedom; secondly, it argues that no one has either the right or the duty to bind himself to an unknown future; finally, it holds that fidelity might prove unfruitful and therefore could represent a significant waste of time.

These objections are evident in current attitudes that question the value of fidelity in marriage. People want to retain the freedom to divorce in principle and especially in circumstances where undesirable changes arise or more attractive alternatives appear. They want the freedom to divorce in the event they cease wanting to be married to each other or develop a preference for the single state or marriage to a different person.

None of these objections, however, is really aimed at the heart of fidelity. Fidelity maintains its covenant of commitment independently of peripheral eventualities. Nonetheless, most if not all great accomplishments, in the arts, sciences, and human relationships, would not have come about without fidelity. Indeed, great accomplishments presuppose fidelity. But in the absence of any assurance that fidelity will lead to such a positive benefit, people recoil, lose heart, and begin to express their misgivings about losing freedom, binding themselves to the unknown, and wasting time. Such fears and negative preoccupations, however, are wholly unproductive. They immobilize and remove all hope.

Fidelity is not contrary to freedom. In fact, there could be no fidelity without freedom. Unless a pledge, promise, or commitment is made from a basis of freedom, it is entirely meaningless. The policy of asking public servants to take oaths implicitly honors their capacity to commit themselves freely to the common good. The marriage vow, expressed by the words "I do", represents a gift of self that is freely given. Moreover, it implies a continuing renewal over the course of a lifetime. The vow that is made in freedom must also be ever renewed in that same spirit. To make a vow and live up to it demands a particularly high degree of freedom. It also implies that one knows that freedom itself is not a terminal value but has meaning only insofar as it is directed toward a higher good.

Although the future is unknown, it is unrealistic never to act in any committed fashion unless we first secure some guarantee that it will necessarily bring about desirable results. As the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard has rightly pointed out, we live forward while we learn backward. The future is not merely a reenactment of the past. It is a horizon of novelty and surprise alongside of defeat and disappointment.

Before we make a serious commitment, it should be emphasized, we must first have a great deal of knowledge about who we are and what we can do. Fidelity demands as much self-knowledge as it does freedom. It also demands courage and hope.

A vow may, indeed, prove unproductive. A spouse may die before the honeymoon is over. A commitment to a particular vocation or course of studies or career may, because of unforeseeable circumstances, be unsustainable. Nonetheless, we must understand that the essential beauty of fidelity lies not so much in its capacity to promise favorable results as in its courage, its hopefulness, and its extraordinary faith in the providential order of things and in the potentialities of each human being. Mother Teresas words offer comfort as well as insight in this regard: "God does not ask us to be successful but to be faithful."

The absence of any capacity to express fidelity results in dissipation rather than freedom, inconstancy rather than realism, and inertia rather than practicality.

The great Christian existentialist Gabriel Marcel assigns a particularly high place to fidelity. We can be faithful to our vows, according to Marcel, not because we have any surety concerning the future states of our feelings, but because we can transcend the moments of our life-flux and express our loyalty to God and, in God, to our fellowmen. It is in Gods presence that a pledge bearing on the future is made.

The soul is in search of its own integrity, or, in religious language, its salvation. The soul cannot find such authenticity by acting for nothing other than what is guaranteed. The complete avoidance of fidelity must inevitably bring about despair. The soul must act in faith, and it must act in accordance with an invocation of the transcendent.[8] Out of essential humility, man recognizes that he is a creaturely being and not an autonomous god. His fidelity, by which he unites himself with the transcendent, is truly a "creative fidelity", one that allows him to realize, more and more, his being and his destiny.

Those

who criticize fidelity do so from want of other virtues, such as self-knowledge,

humility, courage, hope, loyalty to God and neighbor, faith in the ultimate scheme

of things. If we dare reject fidelity itself, however it is expressed — toward

a task, an ideal, or another person — we cannot help but fall into an abyss

of despair.

Endnotes:

- Moose Krause and Stephen Singular, Notre Dames Greatest Coaches (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993), pp. 20-21.

- Jack Connor, Leahys Lads (South Bend, Ind.,: Diamond Communications, 1994).

- Edward W. "Moose" Krause, "The Game That Mimics Life", Notre Dame Magazine, vol. 15, no. 3 (Autumn 1987).

- Krause and Singular, Notre Dames Greatest

Coaches, pp. 150-51.

- Ibid., p. 246.

- Personal communication from Rev. Edward Krause, Jr., C.S.C., October 31, 1994, Gannon University, Erie, Penn.

- Krause, "Game": "The heaviest adversity in my life was when my wife was paralyzed in an automobile accident. For four months she lay close to death. Now, after her partial recovery and years of confinement in a nursing home, we carry on together, but it has been a veritable crucifixion for both of us."

- Gabriel Marcel, Creative Fidelity, trans. Robert Rosthal (New York: Farrar, Straus, 1964) The original title of this work is Du refus à linvocation, p. 167.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

DeMarco, Donald. "Fidelity." In The Heart of Virtue, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1996), 69-76.

Reprinted by permission of Ignatius Press. The Heart of Virtue was published in 1996, ISBN 0-89870-568-1.

The Heart of Virtue: Lessons from Life and Literature Illustrating the Beauty and Value of Moral Character by Donald DeMarco brings to life in an inspirational and memorable way what is at the core of every true moral virtue, namely, love. It presents twenty-eight different virtues and reveals, through stories that personify these virtues, how love is expressed through care, courage, compassion, faith, hope, justice, prudence, temperance, wisdom, etc...The Heart of Virtue is a veritable liberal education in itself, bringing together in a carefully balanced and readable manner, distinguished personalities from diverse enterprises and periods of history. The reader will be both astonished and edified by the determination of Winston Churchill, the compassion of Simone Weil, the courage of Edith Piaf, the humility of Charles Steinmetz, the patience of Walker Percy, the modesty of Flannery OConnor, and the integrity of Jacques and Raissa Maritain.

The Author