Can Catholics Bear Body Art?

- PIA DE SOLENNI

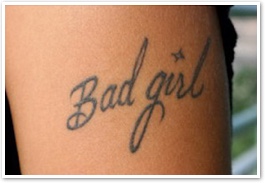

Many good Catholic young people bear on their bodies the trendy markings of their times: tattoos, body piercings and other forms of "body art." Should the Church pretend not to notice the displays or should Catholic adults try to steer young people away from these now-ubiquitous expressions?

Maybe a little historical context will help put the question in perspective. Nearly every society, civilized or otherwise, has been fascinated with the human body. Body art was part of the Egyptian, Greek and Roman civilizations. The persistence of such practices throughout history reveals something about human nature namely that we have a need to manifest belonging. Belonging is part of our identity.

Maybe a little historical context will help put the question in perspective. Nearly every society, civilized or otherwise, has been fascinated with the human body. Body art was part of the Egyptian, Greek and Roman civilizations. The persistence of such practices throughout history reveals something about human nature namely that we have a need to manifest belonging. Belonging is part of our identity.

The desire to enhance the body's beauty is universal, and there's nothing necessarily wrong with it. Bodily adornment can indicate a relation with others, or even with God. The problem in our day is that, like all cultural drives today, it often gets carried to extremes.

The Church has long taught that cosmetics should never be applied to the point where they effectively disguise the identity of the wearer: God should never look down on his creation and be unable to recognize it as his own.

The idea of an indelible mark upon the body can be traced to the mark of Cain in Genesis 4:15. God marked Cain so that no one would dare to kill him as he had Abel. The mark also implies that Cain was not entirely free.

Tattoos, piercings and even brands have been used as religious signs and military signs. They've also been used to indicate ownership, for example, when a slave is marked with his owner's sign. The Nazis tattooed the Jews with identification numbers, thereby reducing their status as persons.

St. Paul, who cut off his hair upon taking a vow (Acts 18:18), said that we are all one in Christ. Outside of Christ, outside of the sacraments, perhaps there is a need to express belonging through a permanent mark on the human body. But, within Christianity, our identity is sealed by baptism. The body will rot away. The worms will get even the tattoos. But the seal of baptism remains.

All of the sacraments have a truly indelible, permanent nature. Unlike a tattoo, which can be removed through a painful process, a marriage is still a marriage even when spouses walk away from each other. The priest, no matter how lacking in holiness he may be, remains a priest forever before God. The sinner may sin again and incur further guilt, but absolution, once given, can never be taken away. That's the beauty of the sacraments: They don't wear off.

Within Christian culture, body art can take on a completely different meaning. It can project a loss of self. Baptism changes our identity from within, but a tattoo permanently changes our external identity. Body art communicates that the value of the person comes from without, not from within. In effect, it signifies that the person plays little role in establishing his identity, as if a person could be determined simply by marks on a body. Christ did not die for people who were marked with an external sign. He died for all because each was equally marked internally with the image of God in which man and woman were created.

As a means of self-expression, body art is wholly external. Tattooing the name of one's beloved on oneself, for example, might be endearing or amusing, but in no way does it create a union with the beloved. (Is it really any wonder that the tattoo-removal business is booming right now?)

When God created the first man and woman, he gave them to each other in a complete way mind, body and soul. Yet neither was marked externally as the property of the other. Living one for the other was the true sign of belonging, a belonging that a tattoo will never communicate. This can only be expressed through sacramental marriage, as Pope John Paul II has often reiterated.

Body art may be OK for those who feel they have no other way to express their identity, but we Christians have been given an identity and a relation that transcends any bodily mark. "The body, and it alone," the Holy Father has said, "is capable of making visible the mystery hidden since time immemorial in God." Our bodies should be the means to revealing this mysteriously beautiful relation.

The body is not the mystery itself; nor can it express the mystery in its entirety. But it is a sign that points to the mystery. It also works as a window or a doorway. The body reveals the identity of the person, but you can't put the identity of the person on the body. Attempts to do so only cheapen the body.

We might ask our young people to think of body art this way: You wouldn't walk up to Leonardo Da Vinci's The Last Supper with a palette and brush and attempt to improve on it by adding your own embellishments. And you certainly wouldn't want to change it to the point that people could no longer tell what the original looked like. So why would you want to alter one of the greatest artist's greatest masterpieces you?

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Pia de Solenni. "Can Catholics Bear 'Body Art'?." National Catholic Register. (August, 2002).

This article is reprinted with permission from National Catholic Register. All rights reserved. To subscribe to the National Catholic Register call 1-800-421-3230.

The Author

Pia de Solenni, a moral theologian based in Washington, D.C., welcomes e-mail at adsum00@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2002 National Catholic Register