Into Great Silence

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

"It's a strange place, Mat," said the young bride, shivering, and looking at the monastery covered in snow.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

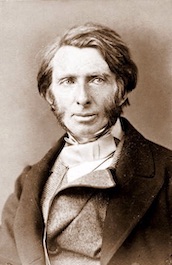

John Ruskin

John Ruskin1819 -1900

Mists rose up from the deep valleys and ravines, and the fir-capped mountains roundabout were lost in clouds. A bell pealed from the tower, and white-robed monks began to appear, leaving their manual labor to congregate in the chapel for prayer.

"I do not know why I am here," said the groom.

"We are on our way to Geneva," she said, "and we'll be spending only a night in this wilderness."

"Yes," he said, but he bowed his head and was troubled.

Soon after, Matthew Arnold would write a poem about witnessing those Carthusian monks, wherein this stanza is to be found:

Wandering between two worlds, one dead,

The other powerless to be born,

With nowhere yet to rest my head,

Like these, on earth I wait forlorn.

Their faith, my tears, the world deride —

I come to shed them at their side.

He had lost his faith in all the supernatural features of the Gospel, had it scoured out of him by the discoveries and the myths of 19th-century science, but he was not joyful about it. Let the world laugh; he did not care. He came to shed tears at the side of the monks whose faith he no longer shared.

Another Victorian man of letters had already come, with his father, to visit the Grande Chartreuse, perched among the slopes of the French Alps. His name was John Ruskin. He had not lost his faith, but, though raised as a Puritan, he had come to devote his life to art and beauty, and good craftsmanship, and to promote the greatness of Catholic painting, sculpture, and architecture in its great days before the high Renaissance. When Ruskin asked one of the monks about the scenery surrounding the house, the man replied, with curled lip, "We do not come here to look at the mountains."

Meanwhile, the life of the monk is both a reproach to our lives of noise and haste, and a quiet and unassuming beacon of hope.

Ruskin bristled at the rebuke. He could not figure out why, then, anybody would come there. But he justified the house for the good work that came from it. Hard-working poverty, and works of charity among men, he said, were the hallmarks of "pure religion," in which neither the Chartreuse's founder, "Saint Bruno himself nor any of his true disciples failed: and I perceive it finally notable of them, that, poor by resolute choice of a life of hardship, without any sentimental or fallacious glorifying of 'holy poverty' as if God had never promised full garners for a blessing; and always choosing men of high intellectual power for the heads of their community, they have had more directly wholesome influence on the outer world than any other order of monks so narrow in number, and restricted in habitation."

Arnold is gone, and peace be with him. He was a good man troubled with bad history and bad theology. He believed that high and noble culture must take the place of faith. Our faith stands tall, but Arnold's is gone; poets and professors themselves mock it. Ruskin is gone, and may God bring him at last among the saints. He was a good man with a Puritan blind spot. He saw that good work was a powerful prayer, but he did not see that prayer was a more powerfully good work.

So we now live in an age of shoddy work and coarse entertainment, of petty poetry and bad art. Yet the Grande Chartreuse stands.

Other visitors

A few years ago a German filmmaker also went to the monastery to learn about a way of life so different from the modern, or we might say so blessedly liberated from the modern. The result was the now-famous film Into Great Silence, which indeed is what its title suggests: a nearly three-hour film that is almost entirely without words.

We see the monks rise before dawn for prayer. We see them gather in the chapel to pray and chant. We see them alone, one at a prie-Dieu, one in his workshop cutting cloth for robes, one in the yard shoveling snow from some garden beds. We see them together in the refectory, eating a spare meal while one reads aloud. We see, one by one, scattered throughout the film, their countenances — old and young, usually grave, with just a trace of good humor visible in the eyes. They seem calm, solid as rock, unsentimental, charitable, wise, hale in body even when old and gray, and ready to greet the Lord.

For me the most moving part of the film is when they interview a very old monk who is now blind. The long white hairs of his eyebrows hang over his eyes like curtains. He is unshaven. He wears a sort of fixed look of benignity and peace in his face, the indelible character of many years.

C'est dommage, he says, a couple of times, "It's a shame, that men have lost the idea of God. We must always begin with the principle that God is infiniment bon," infinitely good, and that all he wills for us is for our great good. "I am glad that he made me go blind," he says, because the blindness was good for his soul. Nor should we fear death. "The Christian should always be happy, never unhappy," he says, because as death comes near he shall be hastening to meet the one who loves us, and who has always seen all of our lives, all that is past and present and to come. He knows what is our good.

A distillery of prayer

Think of it. That house was founded in 1084 by Saint Bruno, who was himself called away, against his will, to do important service for the great reforming Popes Saint Gregory VII and Urban II; yet his heart was ever in the monastic life. For more than nine hundred years, the monks of the Grande Chartreuse have been working, fasting, praying, and awaiting the great day of the Lord. Think of how many great empires and movements of men have in the meantime come and gone: the Holy Roman Empire, the Republic of Venice, the world-girdling Dutch navy, the British Empire, the French revolutionaries, Napoleon, Hitler, the Soviet Union. And still there stands the Grande Chartreuse, and still the monks live silent lives of good cheer, and work and fast and pray on behalf of heedless, harried, and ungrateful man.

Who knows what tremendous things have been wrought by their ceaseless petitions to the eternal and all-present God? Perhaps in the eternal city we shall learn of them at last.

Meanwhile, the life of the monk is both a reproach to our lives of noise and haste, and a quiet and unassuming beacon of hope. It says, "Your lives need not be so." It says, "God was not in the whirlwind, or the earthquake, or the fire, but in the still small voice."

He was a good man with a Puritan blind spot. He saw that good work was a powerful prayer, but he did not see that prayer was a more powerfully good work.

What they are for mankind I think can be described, ironically, by what the world best knows of them. They used to have broad fields for farming, till the French government in the 19th-century seized them. Since then they have supported themselves by distilling the liqueur they have been producing for four hundred years, called Chartreuse. It is made from 130 flowers, herbs, and spices — angelica root, mace, thyme, wormwood, and who knows what else; the full recipe remains a secret, with no more than two monks in possession of it at any time.

Many a mixed drink calls for only a few drops of yellow or green Chartreuse — the liqueur has given its name to its characteristic light green color. The French on their ski slopes like to mix a little bit of Chartreuse in with hot chocolate.

I think that that is a good metaphor for the work of the monks. The world is flashy but insipid. The prayer of men who work close to God and to the earth God made is full of flavor, and can fill the life of man — if we would trouble ourselves to partake of it — with its richness.

Deep calls unto deep

We celebrate in this month the birth of Jesus, though the wise men of our time dryly note that Jesus was probably not born in the dead of night, in the winter. I think you can make a good case for the traditional timing in fact, and surely the mystery of his life, so long hidden, lends it credence. "How silently, how silently, the wondrous gift is given," says the carol. And for thirty years after, Jesus worked and prayed, and worked and prayed, and even when he embarked on his public ministry, he often retreated into the mountains, into the rich and speaking silence of communion with God.

I foresee a time — though our wise men, starless, scoff — when men will say, "Where has the silence gone?" And, weary of living in the flats, they will say, "Look, here's a place where men are silent," as if it were wholly new, just come fresh from the finger of God. Which, of course, it will be. "Take and drink," says Jesus.

It will be one way among many whereby the Church will again, as before, change the world.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: Into Great Silence." Magnificat (December, 2019).

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: Into Great Silence." Magnificat (December, 2019).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2019 Magnificat