Vision and Virtue

- WILLIAM KILPATRICK

Most cultures have recognized that morality, religion, story, and myth are bound together in some vital way, and that to sever the connections among them leaves us not with strong and independent ethical principles but with weak and unprotected ones.

|

One way to counter moral illiteracy is to acquaint youngsters with stories and histories that can give them a common reference point and supply them with a stock of good examples. One of the early calls for returning stories to the curriculum was made by William Bennett in a speech before the Manhattan Institute:

- Do we want our children to know what honesty means? Then we might teach them about Abe Lincoln walking three miles to return six cents and, conversely, about Aesop's shepherd boy who cried wolf.

- Do we want our children to know what courage means? Then we might teach them about Joan of Arc, Horatius at the Bridge, Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad.

- Do we want them to know about kindness and compassion, and their opposites? Then they should read A Christmas Carol and The Diary of Anne Frank and, later on, King Lear.

It's a long list and one that no doubt would have horrified Rousseau. Among the reasons Bennett puts forward in arguing for the primacy of stories are that "unlike courses in moral reasoning," they provide a "stock of examples illustrating what we believe to be right and wrong," and that they "help anchor our children in their culture, its history and traditions. They give children a mooring." "This is necessary," he continues, "because morality, of course, is inextricably bound both to the individual conscience and the memory of society ... We should teach these accounts of character to our children so that we may welcome them to a common world . . ."

Bennett is not liked in teachers colleges and schools of education. He wasn't liked when he was secretary of education, and the legacy he left makes him unpopular still. As education secretary he stood for all those things progressive educators thought they had gotten rid of once and for all. He wanted to reemphasize content not just any content but the content of Western culture. And he wanted to return character education to the schools. His emphasis on stories of virtue and heroism was an affront to the Rousseau/Dewey tradition that had dominated education for years. Furthermore, by slighting "moral reasoning," Bennett also managed to alienate the party of critical thinking. Educators reacted angrily. Bennett was accused of being simplistic, reactionary, and worst of all, dogmatic. William Damon of Brown University, himself the author of a book on moral development, wrote that "Bennett's aversion to conscious moral decision making is itself so misguided as to present a threat to the very democratic traditions that he professes to cherish. Habit without reflection is adaptive only in a totalitarian climate."

Yet Bennett's concern over character was not simply a conservative phenomenon. Liberals too were having second thoughts about a moral education that relied only on moral reasoning. In a 1988 speech that could easily have been mistaken for one of Bennett's, Derek Bok, the president of Harvard University, stated:

Socrates sometimes talked as if knowledge alone would suffice to ensure virtuous behavior. He did not stress the value of early habituation, positive example and obedience to rules in giving students the desire and self-discipline to live up to their beliefs and to respect the basic norms of behavior essential to civilized communities.

Bok went on to call for "a broader effort to teach by habit, example and exhortation," and unlike Bennett, he was speaking not of the elementary or high school but of the university level.

Nevertheless, one still finds a resistance among educators toward the kind of stories Bennett recommends stories that teach by example. I don't mean this in a conspiratorial sense. I find this reaction in student teachers who have never heard of Bennett. Moreover, as far as I know, no committee of educators ever came together to promulgate an anti-story agenda. It has been more a matter of climate, and of what the climate would allow. In my conversations with teachers and would-be teachers, one of the most common themes I hear is their conviction that they simply don't have the fight to tell students anything about right and wrong. Many have a similar attitude toward literature with a moral; they would also feel uneasy about letting a story do the telling for them. The most pejorative word in their vocabulary is "preach." But the loss of stories doesn't strike them as a serious loss. They seem to be convinced that whatever is of value in the old stories will be found out anyway. Some are Rousseauians and believe it will be found out through instinct; others subscribe to some version or other of critical thinking and believe it will be found out through reason.

The latter attitude is a legacy of the Enlightenment, but it is far more widespread now than it ever was in the eighteenth century. The argument then and now is as follows: Stories and myth may have been necessary to get the attention of ignorant farmers and fishermen, but intelligent people don't need to have their ethical principles wrapped in a pretty box; they are perfectly capable of grasping the essential point without being charmed by myths, and because they can reach their own conclusions, they are less susceptible to the harmful superstitions and narrow prejudices that may be embedded in stories. This attitude may be characterized as one of wanting to establish the moral of the story without the story. It does not intend to do away with morality but to make it more secure by disentangling it from a web of fictions. For example, during the Enlightenment the Bible came to be looked upon as an attempt to convey a set of advanced ethical ideas to primitive people who could understand them only if they were couched in story form. A man of the Enlightenment, however, could dispense with the stories and myths, mysteries and miracles, could dispense, for that matter, with a belief in God, and still retain the essence the Christian ethic.

Kohlberg's approach to moral education is in this tradition. His dilemmas are stories of a sort, but they are stories with the juice squeezed out of them. Who really cares about Heinz and his wife (the couple in the stolen drug dilemma)? They are simply there to present a dilemma. And this is the way Kohlberg wanted it. Once you've thought your way through to a position on the issue, you can forget about Heinz. The important thing is to understand the principles involved. Moreover, a real story with well-defined characters might play on a child's emotions and thus intrude on his or her thinking process.

But is it really possible to streamline morality in this way.? Can we extract the ethical kernel and discard the rest? Or does something vital get lost in the process? As the noted short story writer Flannery O'Connor put it, "A story is a way to say something that can't be said any other way ... You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate." In brief, can we have the moral of the story without the story? And if we can, how long can we hold it in our hands before it begins to dissolve?

The danger of such abstraction is that we quickly tend to forget the human element in morality. The utilitarian system of ethics that was a product of the English Enlightenment provides a good illustration of what can happen. It was a sort of debit-credit system of morality in which the rightness or wrongness of acts depended on their usefulness in maintaining a smoothly running social machine. Utilitarianism oiled the cogs of the Industrial Revolution by providing reasonable justifications for child labor, dangerous working conditions, long hours and low wages. For the sake of an abstraction "the greatest happiness for the greatest number" utilitarianism was willing to ignore the real human suffering created by the factory system.

Some of the most powerful attacks on that system can be found in the novels of Charles Dickens. Dickens brought home to his readers the human face of child labor and debtor's prison. And he did it in a way that was hard to ignore or shake off. Such graphic "reminders" may come to us through reading or they may come to us through personal experience, but without them, even the most intelligent and best-educated person will begin to lose sight of the fact that moral issues are human issues.

I use the words "lose sight of' advisedly. There is an important sense in which morality has a visual base or, if you want, a visible base. In other words, there is a connection between virtue and vision. One has to see correctly before one can act correctly. This connection was taken quite seriously in the ancient world. Plato's most famous parable the parable of the cave explains moral confusion in terms of simple misdirected vision: the men in the cave are looking in the wrong direction. Likewise, the Bible prophets regarded moral blindness not only as a sin but as the root of a multitude of sins.

The reason why seeing is so important to the moral life is that many of the moral facts of life are apprehended through observation. Much of the moral law consists of axioms or premises about human beings and human conduct. And one does not arrive at premises by reasoning. You either see them or you don't. The Declaration of Independence's assertion that some truths are "self-evident" is one example of this visual approach to right and wrong. The word "evident" means "present and plainly visible." Many of Abraham Lincoln's arguments were of the same order. When Southern slave owners claimed the same right as Northerners to bring their "property" into the new territories, Lincoln replied: "That is to say, inasmuch as you do not object to my taking my hog to Nebraska, therefore I must not object to your taking your slave. Now, I admit this is perfectly logical, if there is no difference between hogs and Negroes."

Lincoln's argument against slavery is not logical but definitional. It is a matter of plain sight that Negroes are persons. But even the most obvious moral facts can be denied or explained away once the imagination becomes captive to a distorted vision. The point is illustrated by a recent Woody Allen film, Crimes and Misdemeanors. The central character, Judah Rosenthal, who is both an ophthalmologist and a philanthropist, is faced with a dilemma: What should he do about his mistress? She has become possessive and neurotic and has started to do what mistresses are never supposed to do: she has begun to make phone calls to his office and to his home, thus threatening to completely ruin his life a life that in many ways has been one of service. Judah seeks advice from two people: his brother Jack, who has ties to the underworld, and a rabbi, who tries to call Judah back to the vision of his childhood faith. The rabbi (who is nearly blind) advises Judah to end the relationship, even if it means exposure, and to ask his wife for forgiveness. Jack, on the other hand, having ascertained the woman's potential for doing damage and her unwillingness to listen to reason, advises Judah to "go on to the next [logical] step," and he offers to have her "taken care of." The interesting thing is that Jack's reasoning powers are just as good as the rabbi's; and based on his vision of the world, they make perfect sense. You simply don't take the chance that a vindictive person will destroy your marriage and your career. And indeed, Jack finally wins the argument. In an imagined conversation, Judah tells the rabbi, "You live in the Kingdom of Heaven, Jack lives in the real world." The woman is "taken care of."

Jack's reasoning may be taken as an example of deranged rationality or if you change your angle of vision as the only smart thing to do. Certain moral principles make sense within the context of certain visions of life, but from within the context of other visions, they don't make much sense at all. From within the vision provided by the rabbi's faith, all lives are sacred; from Jack's viewpoint, some lives don't count.

Many of the moral principles we subscribe to seem reasonable to us only because they are embedded within a vision or worldview we hold to be true even though we might not think very often about it. In the same way, a moral transformation is often accompanied by a transformation of vision. Many ordinary people describe their moral improvement as the result of seeing things in a different fight or seeing them for the first time. "I was blind but now I see" is more than a line from an old hymn; it is the way a great many people explain their moral growth.

If we can agree that morality is intimately bound up with vision, then we can see why stories are so important for our moral development, and why neglecting them is a serious mistake. This is because stories are one of the chief ways by which visions are conveyed (a vision, in turn, may be defined as a story about the way things are or the way the world works). Just as vision and morality are intimately connected, so are story and morality. Some contemporary philosophers of ethics most notably, Alasdair MacIntyre now maintain that the connection between narrative and morality is an essential one, not merely a useful one. The Ph.D. needs the story "part" just as much as the peasant. In other words, story and moral may be less separable than we have come to think. The question is not whether the moral principle needs to be sweetened with the sugar of the story but whether moral principles make any sense outside the human context of stories. For example, since I referred earlier to the Enlightenment habit of distilling out the Christian ethic from the Bible, consider how much sense the following principles make when they are forced to stand on their own: ·

- Do good to those that harm you.

- Turn the other cheek.

- Walk an extra mile.

- Blessed are the poor.

- Feed the hungry.

"Feed the hungry" seems to have the most compelling claim on us, but just how rational is it.? Science doesn't tell us to feed the hungry. Moreover, feeding the hungry defeats the purpose of natural selection. Why not let them die and thus "decrease the surplus population" as Ebenezer Scrooge suggests? Fortunately, the storyteller in this case takes care to put the suggestion in the mouth of a disagreeable old man.

Of course, there are visions or stories or ways of looking at life other than the Christian one, from which these counsels would still make sense. On the other hand, from some points of view they are sheer nonsense. Nietzsche, one of the great geniuses of philosophy, had nothing but contempt for the Christian ethic.

In recent years a number of prominent psychologists and educators have turned their attention to stories. In The Uses of Enchantment (1975), child psychiatrist Bruno Bettelheirn argued that fairy tales are a vital source of psychological and moral strength; their formative power, he said, had been seriously underestimated. Robert Coles of Harvard University followed in the 1980s with three books (The Moral Life of Children, The Spiritual Life of Children, and The Call of Stories) which detailed the indispensable role of stories in the life of both children and adults. Another Harvard scholar, Jerome Bruner, whose earlier The Process of Education had helped stimulate interest in critical thinking, had, by the mid-eighties, begun to worry that "propositional thinking" had been emphasized at the expense of "narrative thinking"- literally, a way of thinking in stories. In Actual Minds, Possible Worlds, Bruner suggests that it is this narrative thought, much more than logical thought, that gives meaning to life.

A number of other psychologists had arrived at similar conclusions. Theodore Sarbin, Donald Spence, Paul Vitz, and others have emphasized the extent to which individuals interpret their own lives as stories or narratives. "Indeed," writes Vitz, "it is almost impossible not to think this way." According to these psychologists, it is such narrative plots more than anything else that guide our moral choices. Coles, in The Moral Life of Children, observes how the children he came to know through his work not only understood their own lives in a narrative way but were profoundly influenced in their decisions by the stories, often of a religious kind, they had learned.

By the mid-eighties a similar story had begun to unfold in the field of education. Under the leadership of Professor Kevin Ryan, Boston University's Center for the Advancement of Character and Ethics produced a number of position papers calling for a reemphasis on literature as a moral teacher and guide. Meanwhile, in Teaching as Storytelling and other books, Kieran Egan of Canada's Simon Fraser University was proposing that the foundations of all education are poetic and imaginative. Even logico-mathematical and rational forms of thinking grow out of imagination, and depend on it. Egan argues that storytelling should be the basic educational method because it corresponds with fundamental structures of the human mind. Like Paul Vitz, he suggests that it is nearly impossible not to think in story terms. "Most of the world's cultures and its great religions," he points out, "have at their sacred core a story, and we indeed have difficulty keeping our rational history from being constantly shaped into stories."

In short, scholars in several fields were belatedly discovering what Flannery O'Connor, with her writer's intuition, had noticed years before: "A story is a way to say something that can't be said any other way. . ."

This recent interest in stories should not, however, be interpreted as simply another Romantic reaction to rationalism. None of the people I have mentioned could be classified as Romanticists. Several of them (including Flannery O'Connor) freely acknowledge their indebtedness to Aristotle and Aquinas to what might be called the "realist" tradition in philosophy. Although literature can be used as an escape, the best literature, as Jacques Barzun said, carries us back to reality. It involves us in the detail and particularity of other lives. And unlike the superficial encounters of the workaday world, a book shows us what other lives are like from the inside. Moral principles also take on a reality in stories that they lack in purely logical form. Stories restrain our tendency to indulge in abstract speculation about ethics. They make it a little harder for us to reduce people to factors in an equation.

I can illustrate the overall point by mentioning a recurrent phenomenon in my classes. I have noticed that when my students are presented with a Values Clarification strategy and then with a dramatic account of the same situation, they respond one way to the dilemma and another to the story. In the Values Clarification dilemma called "The Lifeboat Exercise," the class is asked to imagine that a ship has sunk and a lifeboat has been put out from it. The lifeboat is overcrowded and in danger of being swamped unless, the load is lightened. The students are given a brief description of the passengers a young couple and their child, an elderly brother and sister, a doctor, a bookkeeper, an athlete, an entertainer, and so on and from this list they must decide whom to throw overboard. Consistent with current thinking, there are no right and wrong answers in this exercise. The idea is to generate discussion. And it works quite well. Students are typically excited by the lifeboat dilemma.

This scenario, of course, is similar to the situation that faced the crew and passengers of the Titanic when it struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic in 1912. But when the event is presented as a story rather than as a dilemma, the response evoked is not the same. For example, when students who have done the exercise are given the opportunity to view the film A Night to Remember, they react in a strikingly different way. I've watched classes struggle with the lifeboat dilemma, but the struggle is mainly an intellectual one like doing a crossword puzzle. The characters in the exercise, after all, are only hypothetical. They are counters to be moved around at will. We can't really identify with them, nor can we be inspired or repelled by them. They exist only for the sake of the exercise.

When they watch the film, however, these normally blasé college students behave differently. Many of them cry. They cry as quietly as possible, of course: even on the college level it is extremely important to maintain one's cool. But this is a fairly consistent reaction. I've observed it in several different classes over several years. They don't even have to see the whole film. About twenty minutes of excerpts will do the trick.

What does the story do that the exercise doesn't? Very simply, it moves them deeply and profoundly. This is what art is supposed to do.

If you have seen the film, you may recall some of the vivid sketches of the passengers on the dying ship as the situation becomes clear to them: Edith Evans, giving up a place on the last boat to Mrs. Brown, saying, "You go first; you have children waiting at home." Harvey Collyer pleading with his wife, "Go, Lottie! For God's sake, be brave and go! I'll get a seat in another boat." Mrs. Isidor Straus declining a place in the boats: "I've always stayed with my husband, so why should I leave him now?"

The story is full of scenes like this: Arthur Ryerson stripping off his life vest and giving it to his wife's maid; men struggling below decks to keep the pumps going in the face of almost certain death; the ship's band playing ragtime and then hymns till the very end; the women in boat 6 insisting that it return to pick up survivors; the men clinging to the hull of an overturned boat, reciting the Lord's Prayer; the Carpathia, weaving in and out of ice floes, racing at breakneck speed to the rescue. But there are other images as well: the indolence and stupidity of the California's crew who, only ten miles away, might have made all the difference, but did nothing; the man disguised in a woman's shawl; the panicked mob of men rushing a lifeboat; passengers in half-empty lifeboats refusing to go back to save the drowning.

The film doesn't leave the viewer much room for ethical maneuvering. It is quite clear who has acted well and who has not. And anyone who has seen it will come away hoping that if ever put to a similar test, he or she will be brave and not cowardly, will think of others rather than of self.

Not only does the film move us, it moves us in certain directions. It is definitive, not open-ended. We are not being asked to ponder a complex ethical dilemma; rather, we are being taught what is proper. There are codes of conduct: women and children first; duty to others before self. If there is a dilemma in the film, it does not concern the code itself. The only dilemma is the perennial one that engages each soul: conscience versus cowardice, faith versus despair.

This is not to say that the film was produced as a moral fable. It is, after all, a true story and a gripping one, the type of thing that almost demands cinematic expression hardly a case of didacticism. In fact, if we were to level a charge of didacticism, it would have to be against "The Lifeboat Exercise." It is quite obviously an artificially contrived teaching exercise. But this is didacticism with a difference. "The Lifeboat Exercise" belongs to the age of relativism, and consequently, it has nothing to teach. No code of conduct is being passed down; no models of good and bad behavior are shown. Whether it is actually a good or bad thing to throw someone overboard is up to the youngster to decide for himself. The exercise is designed to initiate the group into the world of "each man his own moral compass."

Of course, we are comparing two somewhat different things: a story, on the one hand, and a discussion exercise, on the other. The point is that the logic of relativism necessitates the second approach. The story of the Titanic was surely known to the developers of "The Lifeboat Exercise." Why didn't they use it? The most probable answer is the one we have alluded to: The story doesn't allow for the type of dialogue desired. It marshals its audience swiftly and powerfully to the side of certain values. We feel admiration for the radio operators who stay at their post. We feel pity and contempt for the handful of male passengers who sneak into lifeboats. There are not an infinite number of ways in which to respond to these scenes, as there might be to a piece of abstract art. Drama is not the right medium for creating a value-neutral climate. It exerts too much moral force.

Drama also forces us to see things afresh. We don't always notice the humanity of the person sitting next to us on the bus. It is often the case that human beings and human problems must be presented dramatically for us to see them truly. Robert Coles relates an interesting anecdote in this regard about Ruby Bridges, the child who first integrated the New Orleans schools. Ruby had seen A Raisin in the Sun, and expressed to Coles the wish that white people would see it: "If all the [white] people on the street [who were heckling her mercilessly] saw that movie, they might stop coming out to bother us." When Coles asked her why she thought that, she answered, "Because the people in the movies would work on them, and maybe they'd listen." Ruby knew that whites who saw her every day didn't really see her. Maybe the movie would make them see.

Admittedly, I have been mixing media rather freely here, and this raises a question. Films obviously have to do with seeing, but how about books? The paradoxical answer is that the storyteller's craft is not only a matter of telling but also of showing. This is why writing is so often compared to painting, and why beginning writers are urged to visualize what they want to say. So, even when a writer has a moral theme, his work if he is a good writer is more like the work of an artist than a moralist. For example, C. S. Lewis's immensely popular children's books have strong moral and religious themes, but they were not conceived out of a moral intent. "All my seven Narnian books," Lewis wrote in 1960, "and my three science fiction books, began with seeing pictures in my head. At first they were not a story, just pictures. The Lion [The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe] all began with a picture of a faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood."

Stories are essentially moving pictures. That is why they are so readily adaptable to the screen. And a well-made film, in turn, needs surprisingly little dialogue to make its point. When, in A Night to Remember, the shawl is torn away from the man's head, we do not have to be told anything. We see that his behavior is shameful; it is written on his face.

On the simplest level the moral force of a story or film is the force of example. It shows us examples of men and women acting well or trying to act well, or acting badly. The story points to these people and says in effect, "Act like this; don't act like that." Except that, of course, nothing of the kind is actually stated. It is a matter of showing. There is, for instance, a scene in Anna Karenina in which Levin sits by the side of his dying brother and simply holds his hand for an hour, and then another hour. Tolstoy doesn't come out and say that this is what he ought to do, but the scene is presented in such a way that the reader knows that it is the right thing to do. It is, to use a phrase of Bruno Bettelheim's, "tangibly right."

"Do I have to draw you a picture?" That much used put-down implies that normally intelligent people can do without graphic illustration. But when it comes to moral matters, it may be that we do need the picture more than we think. The story suits our nature because we think more readily in pictures than in propositions. And when a proposition or principle has the power to move us to action, it is often because it is backed up by a picture or image. Consider, for example, the enormous importance historians assign to a single book Uncle Tom's Cabin in galvanizing public sentiment against slavery. After the novel appeared, it was acted out on the stage in hundreds of cities. For the first time, vast numbers of Americans had a visible and dramatic image of the evils of slavery. Lincoln, on being introduced to author Harriet Beecher Stowe, greeted her with the words "So this is the little lady who started the big war." In more recent times the nation's conscience has been quickened by photo images of civil rights workers marching arm in arm, kneeling in prayer, and under police attack. It is nice to think that moral progress is the result of better reasoning, but it is naive to ignore the role of the imagination in our moral life.

The more abstract our ethic, the less power it has to move us. Yet the progression of recent decades has been in the direction of increasing verbalization and abstraction, toward a reason dissociated from ordinary feelings and cut off from images that convey humanness to us. "At the core of every moral code," observed Walter Lippmann, "there is a picture of human nature." But the picture coming out of our schools increasingly resembles a blank canvas. The deep human sympathies the kind we acquire from good literature are missing.

Perhaps the best novelistic portrait of disconnected rationalism is that of Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment. Raskolnikov has mastered the art of asking the question "Why not?" What is wrong with killing a repulsive old woman? he asks himself. What is wrong with taking her money and using it for a worthy cause namely, to pay for his own education? With that education, Raskolnikov eventually plans to bring his intellectual gifts to the service of mankind. It is good utilitarian logic.

In commenting on Crime and Punishment, William Barrett observes that in the days and weeks after the killing, "a single image breaks into this [Raskolnikovs] thinking." It is the image of his victim, and this image saves Raskolnikov's soul. Not an idea but an image. For Dostoevsky the value of each soul was a mystery that could never be calculated but only shown.

The same theme recurs in The Brothers Karamazov. At the very end of the book, Alyosha speaks to the youngsters who love him: "My dear children ... You must know that there is nothing higher and stronger and more wholesome and useful for life in after years than some good memory, especially a memory connected with childhood, with home. People talk to you a great deal about your education, but some fine, sacred memory, preserved from childhood, is perhaps the best education. If a man carries many such memories with him into life, he is safe to the end of his days, and if we have only one good memory left in our hearts, even that may sometime be the means of saving us."

There is no point in trying to improve on this. Let us only observe that what Dostoevsky says of good memories is true also of good stories. Some of our "sacred" memories may find their source in stories.

We carry around in our heads many more of these images and memories than we realize. The picture of Narcissus by the pool is probably there for most of us; and the Prodigal Son and his forgiving father likely inhabit some comer of our imagination. Atticus Finch, Ebenezer Scrooge, Laura Ingalls Wilder, Anne Frank, David and Goliath, Abraham Lincoln, Peter and the servant girl: for most of us these names will call up an image, and the image will summon up a story. The story in turn may give us the power or resolve to struggle through a difficult situation or to overcome our own moral sluggishness. Or it may simply give us the power to see things clearly. Above all, the story allows us to make that human connection we are always in danger of forgetting.

Most cultures have recognized that morality, religion, story, and myth are bound together in some vital way, and that to sever the connections among them leaves us not with strong and independent ethical principles but with weak and unprotected ones. What "enlightened" thinkers in every age envision is some sort of progression from story to freestanding moral principles unencumbered by stories. But the actual progression never stops there. Once we lose sight of the human face of principle, the way is clear for attacking the principles themselves as merely situational or relative. The final stage of the progression is moral nihilism and the appeal to raw self-interest the topics of the next chapter.

![]()

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

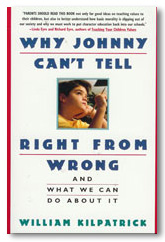

Kilpatrick, William. "Vision and Virtue." Chapter 7 in Why Johnny Can't Tell Right from Wrong and What We Can Do About It. edited by J.H. Clarke, (New York: A Touchstone Book, 1992), 129-143.

Reprinted by permission of William Kilpatrick.

The Author

William Kilpatrick is the author of several books on religion and culture including Christianity, Islam, and Atheism: The Struggle for the Soul of the West and Why Johnny Can't Tell Right from Wrong. For more on his work and writings, visit his Turning Point Project website.

Copyright © 1993 Touchstone books