Thomas Hughe's Tom Brown's School Days

- MITCHELL KALPAKGIAN

A heartwarming, charming story of a typical English boy's life at Dr. Arnold's famous Rugby school renowned for its ethic of "muscular Christianity, this classic (1857) depicts the old world ideals of "merry old England" captured in the customs of rural villages and transmitted at Rugby.

This traditional culture rooted in the love of the land and the family conflicts with the progressive new world of industrialism that subverts the simple English country way of life. Hughes laments that the railroad and the fashion of travel have revolutionized the rhythm and order of human life and converted England into "a vagabond nation" with "gadabout propensities."

This false sophistication and pseudo cosmopolitanism, according to Hughes, subverts the Englishman's attachment to his country, culture, and family. The novelty of restless travel deprives an Englishman of his ancient Christian heritage. To Hughes civilization abounds in England in such historical shrines as the Vale of White Horse, the site of an ancient Roman camp, and the sacred ground of Ash-down where King Alfred "broke the Danish power, and made England a Christian land" — venerable places rich in glorious history and legend abandoned by a younger generation lured by the glamour of travel to the European continent and by the temptation of wealth to the industrial cities. Hughes laments, "Too much over-civilization, and the deceitfulness of riches." For Hughes the country is the center of culture, not the city, and the family the center of civilization, not London.

Against these trends and the new utilitarian schools of education that Hughes calls "Mechanics' Institutes," the novel presents the old-fashioned Brown family and the Rugby school that uphold classical liberal education and the best of England's Christian patrimony. One tradition in decline because of the new mobility of railway travel is the custom of "The Veast," a traditional country fair that features wrestling, backswording, sack races, a Punch and Judy show, and "jingling matches" in which blindfolded men enter a ring and attempt to catch a man with a bell around his neck and hands tied behind his back. The crowd roars when "half of the men blindly rush into the arms of the other half, or drove their heads together, or tumble over." Young and old and members from all the social classes in the village revel in the mirth of the occasion as they dress in their Sunday best, savor country cooking, and feel united as a people bound by their ancient traditions. The new economic trends of the day ("buying cheap and selling dear, and its accompanying over-work") and the enticement of fast travel ("our sons and daughters have their hearts in London Club-life, or so-called Society") have fragmented an integrated English way of life in tune with Mother Nature's rhythms of work and play and in harmony with the past.

An exquisite sense of accomplishment awaits the honorable Rugby way that pursues the good no matter the cost or sacrifice.

Rugby, on the other hand, transmits the time-honored familial and moral ideals of merry old England cherished by the families who send their sons to the school to become Christian gentlemen, to learn the virtues of honor and integrity, to acquire a seriousness of purpose in the form of earnestness and dutifulness, and to learn that "There's always a highest way, and it's always the right one." Squire Brown explains his expectations of a Rugby education: "If he'll only turn out a brave, helpful, truth-telling Englishman, and a gentleman, and a Christian, that's all I want." Rugby, then, forms character, produces leaders, teaches magnanimity, and cultivates manliness, the virtues of "pluck" or "mettle" especially displayed on the playing fields.

As young Tom mounts the stagecoach on a cold November morning at 2:00 a.m., he receives a preliminary initiation into the ethos of Rugby: "the silent endurance, so dear to every Englishman — of standing out against something, and not giving in." This strong, unflinching determination of noble endurance, as Tom will learn in his education, relates also to athletics and to the moral life. As the travelers reach the inn for breakfast and see the blazing fire and decorated table covered with a plentiful breakfast of cold meats, poached eggs, toast and muffins, Tom glimpses the spirit of Rugby that awaits him at the school: "Have we not endured nobly this morning, and is not this a worthy reward for much endurance?" An exquisite sense of accomplishment awaits the honorable Rugby way that pursues the good no matter the cost or sacrifice.

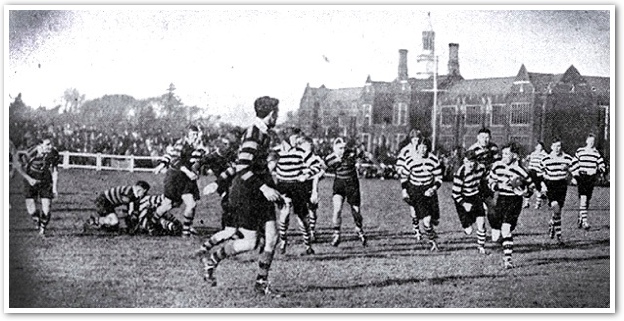

The same aura of manly endurance and tireless strength greets Tom on his first day at the school when he plays rugby the entire afternoon with the renowned "pluck" and "mettle" demanded by the sport. After hours of vigorous running, Tom daringly plunges on a loose ball with older, heavier boys knocking the wind out of the small boy. "Bravo, youngster, you played famously," cries Brooke, the oldest boy at the school befriending the newest student and paying him the highest compliment: "Well, he is a plucky youngster, and will make a player." Tom's introductions to Rugby in the coach ride and in the rugby match capture the ideal of "muscular Christianity" that Dr. Arnold instilled in the school. The mettle cultivated in sports not only developed the physical stamina to defeat an opponent but also formed the moral courage and will power to fight evil.

Tom Brown's School Days

by Thomas Hughes |

The end of a Rugby education, then, is the formation of young spirited boys like Tom Brown into noble leaders like Brooke who act by the highest moral principles rather than pander to popularity. No honorable young man stoops to bullying, lying, or cheatingthe most contemptible vices at the school. Dr. Arnold's constant teaching instructs the boys that life is "no fool's or sluggard's paradise" but "a battlefield ordained from of old" with the stakes of life and death. In his education Tom learns to acquire this moral strength that contends against "whatever was mean and unmanly and unrighteous in our little world" as he fights and defeats cruel bullies like Flashman. Tom learns to control his daring, energy, and wildness that often lead to punishment and near expulsion. Tom conquers sloth and abandons the dishonesty of using "cribs" to do his Latin and Greek translations. Tom experiences an awakening of conscience and prays before bed despite the heckling of other boys who ridicule the practice as unmanly. In short, Tom integrates mind, body, heart, and soul as he acquires the intellectual honesty of a good student, the will power of the disciplined athlete, the true heart of a loyal friend, and the Christian conscience that seeks "the things that are above" that distinguish Rugby's liberal education from the utilitarian schools of the day that only prepare for the economic life.

The story portrays Tom's schooldays from his first day on the rugby field as the plucky youngster to his last day at the school as the principled captain of the cricket team. The mischievous, fun-loving boy of an English village matures into a Christian gentleman who is ruled by magnanimity. In the acclaimed cricket match between Rugby and London, Tom makes a difficult decision guided by a sense of honor and justice rather by popular opinion and the vainglory of winning. When Tom decides to let George Arthur bat instead of another hitter known as "the best bat left," Tom is ruled by his sense of fair play and integrity rather than victory at all costs. He remarks, "But I couldn't help putting him in. It will do him so much good, and you can't think what I owe him."

Tom's leadership shows excellent judgment as Arthur plays an outstanding game even though Rugby loses the close match. Despite the heartbreaking loss "such a defeat is a victory: so think Tom and all the School eleven" as he receives the highest tribute from the opposing team: "I must compliment you, sir, on your eleven." The rambunctious boy who thrived on fun, sports, and adventure graduates with a large mind, heart, and soul ruled by a sense of duty to others, a sense of honor inspired by the highest ideals, and by a sense of manly fortitude on the playing field and in the struggles of the moral life.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Mitchell A. Kalpakgian. "Thomas Hughes' Tom Brown's School Days." Crisis Magazine (July 2, 2012).

Reprinted with permission of Crisis Magazine.

Crisis Magazine is an educational apostolate that uses media and technology to bring the genius of Catholicism to business, politics, culture, and family life. Our approach is oriented toward the practical solutions our faith offers — in other words, actionable Catholicism.

The Author

Mitchell A. Kalpakgian was Professor of English at Simpson College (Iowa) for 31 years. During his academic career, Dr. Kalpakgian received many academic honors, among them the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Seminar Fellowship (Brown University, 1981); the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship (University of Kansas, 1985); and an award from the National Endowment for the Humanities Institute on Children's Literature. He is the author of The Marvelous in Fielding's Novels and The Mysteries of Life in Children's Literature. His favorite activities include writing, long distance running, and coaching soccer.Copyright © 2012 Crisis Magazine

Mitchell A. Kalpakgian was Professor of English at Simpson College (Iowa) for 31 years. During his academic career, Dr. Kalpakgian received many academic honors, among them the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Seminar Fellowship (Brown University, 1981); the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship (University of Kansas, 1985); and an award from the National Endowment for the Humanities Institute on Children's Literature. He is the author of The Marvelous in Fielding's Novels and The Mysteries of Life in Children's Literature. His favorite activities include writing, long distance running, and coaching soccer.Copyright © 2012 Crisis Magazine