The saint and the sculptor

- AMY GIULIANO

In 1862, a young sculptor; mourning the sudden death of his beloved sister, sought to enter religious life.

"A genius conceives a masterpiece…. He is delighted with it; he will realize it by every possible means and at the cost of any sacrifice…. He is dominated by his masterpiece; he sees it continually. Well, [in like manner,] fix your mind on our Lord in the Most Blessed Sacrament and ponder on his love." - Saint Peter Julian Eymard

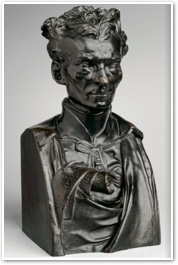

Pierre-Julien Eymard (1863)

Pierre-Julien Eymard (1863)Auguste Rodin (1840-1917)

The Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA, USA

In 1862, a young sculptor; mourning the sudden death of his beloved sister, sought to enter religious life. He chose the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament, a community founded only six years earlier by the saintly priest Peter Julian Eymard (1811-1868). Eymard recognized in this lost young man an extraordinary artistic talent, still in its nascency; he also recognized, however, that the man did not have a religious vocation. The priest transformed a garden shed on the community's property into a studio for the novice, and encouraged him to continue with his art while he found his way back to lay life — which he eventually did, but not before creating a masterful bust of Eymard, his beloved spiritual father. That young novice, Auguste Rodin, went on to become one of the most illustrious artists of his time, creating such masterpieces as The Thinker, The Burghers of Calais, and The Kiss.

Peter Julian Eymard, now canonized and feted by the Church as the Apostle of the Eucharist, valued such artistic creativity as Rodin's. When he established houses of public Eucharistic Adoration, Eymard insisted that these "Cenacles be oases not only of prayer, but also of beauty: The Gospel tells us...that [for the Last Supper] Jesus chose a 'large furnished room.' What an astonishing thing! Jesus always sought out poor houses and here we find a kind of sumptuousness. For the Eucharist, nothing is too beautiful." This sentiment inspired Eymard's quest to dedicate creative genius in architecture, painting, and sculpture to the honor of the Blessed Sacrament.

Rodin's bust of Eymard and The Thinker

Rodin's bust of Eymard, considered one of his early masterpieces, is a living likeness of the saint, who looks beyond the viewer with a transfixed gaze. The strong V-shaped angles of Eymard's hairline, face, and priestly garb open and project outwards; the play of light and shadow across his deftly modeled features imitates a flame flickering upwards. His lean face, accentuated by large cheekbones and strong eyebrows, sets forth wonderfully wide, bright eyes. Eymard's intense visage, crowned with unruly locks, is counterbalanced try the organic curves of the scroll unfurling from under his cape, as if overflowing from his heart. The scroll is inscribed with Eymard's famous prayer: "O Sacrament most holy, O Sacrament divine, all praise and all thanksgiving be every moment thine!" The bust evokes the fiery dynamism of one whose greatest passion in life was to fix his gaze on the Eucharist. Eymard was no stranger to the cross, yet his face is not marred by suffering, The sculpture depicts the spiritual father who had inspired his famous novice — a man set alight, transfigured by the presence of God.

Rodin's most celebrated work, The Thinker (1880), provides an instructive visual counterpoint to his bust of Eymard, underscoring the significance of Rodin's artistic choices in his portrayal of the saint of Eucharistic adoration: The Thinker's powerful athletic body closes inward, fist pressed to his teeth, eyes shrouded in shadow under a tensely knit brow, his imposing frame bent under the weight of his anxious consideration.

Vision of hell, vision of heaven

The brooding figure of The Thinker, originally titled The Poet and intended to be a metaphorical representation of Dante Alighieri, was designed to crown Rodin's The Gates of Hell, a monumental set of bronze doors inspired by Dante's Inferno. Perched in the tympanum over the lintel of The Gates of Hell, Rodin's Thinker gazes downwards, contemplating the torments of the damned souls writhing in an inferno that he has described but does not presume to judge. Rather, his closed posture and solemn expression indicate his personal identification with the distress of the damned. Grappling with his own broken human nature and the pain of sin, his body language mimics these denizens of the inferno — figures characterized by dark psychological anguish and isolating self-absorption. The Thinker's flexed musculature simultaneously reveals the agitation of his internal suffering and his frustrated yearning to transcend it.

The brooding figure of The Thinker, originally titled The Poet and intended to be a metaphorical representation of Dante Alighieri, was designed to crown Rodin's The Gates of Hell, a monumental set of bronze doors inspired by Dante's Inferno. Perched in the tympanum over the lintel of The Gates of Hell, Rodin's Thinker gazes downwards, contemplating the torments of the damned souls writhing in an inferno that he has described but does not presume to judge. Rather, his closed posture and solemn expression indicate his personal identification with the distress of the damned. Grappling with his own broken human nature and the pain of sin, his body language mimics these denizens of the inferno — figures characterized by dark psychological anguish and isolating self-absorption. The Thinker's flexed musculature simultaneously reveals the agitation of his internal suffering and his frustrated yearning to transcend it.

In stark contrast. Rodin's bust of Eymard is incandescent. tacitly echoing the song of the Psalmist, Look to him, that you may be radiant with joy (cf. Ps 34:6). The bust's unruly hair, which Eymard ruefully compared to horns, is likely Rodin's oblique reference to Moses, whose face emitted rays of light (famously mistranslated as "horns" in Jerome's Vulgate) after his encounters with God. These fiery locks also form something of a transfigured crown of thorns ringing the saint's head. Pockets of shadow across his face appear and disappear as one moves around the bust, conveying the inner energy of the saint and underscoring the intensity of his eyes, which steadily reflect the light from all angles. Large and almond-shaped, almost childlike in their openness, these smooth. rounded planes glow with the sheen of the polished bronze.

Transfigured by the divine artist

In the bust of Eymard, Rodin left us with an archetypal image of the adorer. Through the gift of Eucharistic Adoration, the closed, burdened soul of natural man opens in the presence of the Divine Artist, allowing him to perfect his masterpiece. Accepting the pain and brokenness we bring him, he transforms our deepest wounds into our souls' most distinctively beautiful features. As Augustine says, "I gazed into my deepest wound and was dazzled by your glory." This glory of the Divine Artist shines powerfully through his creation. After spending time in the presence of the Eucharist, we, like Eyrnard. leave revived, set alight with indefinable radiance. This claritas is the elusive yet distinctive mark of an encounter with Christ as Sacred Beauty, an encounter in which he himself is the creative genius and we are his beloved, precious masterpieces.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Amy Giuliano. "The saint and the sculptor." Magnificat (August, 2017).

Amy Giuliano. "The saint and the sculptor." Magnificat (August, 2017).

Reprinted with permission of Magnificat.

The Author

Amy Giuliano holds degrees in Religion and the Visual Arts from Yale, Theology from the Angelicum in Rome, and Catholic Studies from Seton Hall University. She teaches Art History and Catholic Studies at Sacred Heart University, writes sacred art essays for the Magnificat, and travels the world creating virtual tours of the Church's artistic patrimony.

Copyright © 2017 Magnificat