The Language of Beauty - part 5: The Power of Names

- PETER KREEFT

If things come to us in their names, then the power of things comes to us in the power of their names.

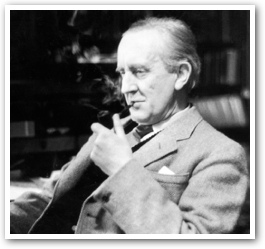

J. R. R. Tolkien

J. R. R. Tolkien

So words have a magical power, a power not just to communicate intellectually, not just to suggest emotionally, but power which can produce physical effects. Now here's a claim that most of you will probably be sceptical of. And maybe I'm wrong in thinking that Tolkien believed this, and maybe I'm wrong in thinking that it is in some way true. But maybe I'm not, so contemplate this rather striking notion.

Look at Tom Bombadil in The Lord of the Rings. His words save Merry from Old Man Willow, and then they save Frodo from the Barrow-wight. Why? As he explains: "None has ever caught him yet, for Tom, he is the master: His songs are stronger songs, and his feet are faster." [1] "His songs are stronger songs." Are God's songs the strongest songs? Yes. What are God's songs? Prayers. Or things wrought by prayer that the world only dreams of.

Frodo, too, uses the magical power of words when he calls Tom's name. Two miracles happen, one spiritual and one physical. First, "with that name, Frodo's voice seemed to grow strong." [2] Second, Tom actually comes! If we find this unconvincing, it shows how little we have taken God at his word, when He repeatedly promises the same thing Bombadil did. To put the Biblical promise in contemporary words, "You just call out my name, and you know wherever I am, I'll come running to see you again. Winter, spring, summer or fall, all you've got to do is call, and I'll be there, yeah, yeah, yeah; I've got a friend." Thus endeth the daily devotional reading from the prophet James. I think James Taylor deliberately meant that. Taylor's been through hard times, but he's a very religious man. If you get a chance, listen to his new hymn it's about two or three years old, but, moving.

Are there magic words? I think we all know there are; there are operative words. There are words that, whatever you believe theologically, are sacraments; they effect what they signify. I'll give you two that everybody knows are sacramental words: "I love you" and "I hate you". And for anybody who has any liturgical understanding, "I baptize thee", or "This is My body". These are not labels; they're spiritual weapons. They're arrows that pierce through flesh and into hearts.

Well, in a lesser but real way, the whole of The Lord of the Rings is an armour-piercing rocket that can get into your underground bunkers, your inner Afghanistans or Iraqs. And the most powerful of these arrows are the proper names, the names of persons, or places. When the Black Rider bangs on Fatty Bolger's door in Buckland saying, "Open in the name of Mordor," all the authority and terror and power of Mordor are really present there.

When Frodo on Weathertop faces the Black Rider, "he heard himself crying aloud: 'O Elbereth! Gilthoniel!'" [3] He's speaking in tongues – He doesn't understand Elvish – as he strikes the Rider with his sword. Afterwards Aragorn commented on this event; he said, "all blades perish that pierce that dreadful King. More deadly to him was the name of Elbereth." [4] Frodo again speaks in tongues in Shelob's lair. "'Aiya Eärendil Elenion Ancalima!' he cried, and knew not what he had spoken; for it seemed that another voice spoke through his." [5]

And when the tiny hobbit with the tiniest sword advanced on the most hideous creature in all of Middle-Earth with the phial of Galadriel, and in the name of Galadriel and El-Bereth, Shelob cowered. And later Sam did the same thing. "'Galadriel,' he said faintly, and then heard faintly voices far off but clear, the cry of the Elves as they walked under the stars in the beloved shadows of the Shire, and the music of the Elves 'Gilthoniel A Elbereth!' And then his tongue was loosed and his voice cried in a language which he did not know" [6] He's not merely remembering his little dead picture of the live Elves. Somehow those Elves are made present. Because Shelob is not afraid of somebody's memories – Shelob is afraid of Elves.

What's in a name? In the name of Jesus, devils were exorcised. Hell was defeated. Heaven's gate was opened. What's in a name? In a name the whole universe was created. Everything is in a name, because that name was the Word of God, the mind of God, the logos. What's in a name? Moses asked God that question at the burning bush, and God answered I Am.

There's an old myth of an original language. It's in the Bible: the story of the tower of Babel – which is beginning to be undone by Pentecost. It's in Plato, in his Dialogue with the Kratulus. It's not a popular idea anymore, but it's in a lot of classical literature. Once upon a time, there was not only one language, but the right language, the perfect language. Well, if that is true, that would explain why every proper name of Tolkien's seems exactly right. That's a power even his critics marvel at. When we read those names, we're remembering; we're doing Plato's anamnesis unconsciously; our cognition is a re-cognition, a recognition. Our word detector buzzes when we meet the right word, the Platonic ideal, the Jungian archetype. We experience discovery rather than invention.

|

The true name is one which expresses the character, the nature, the meaning of the person who bears it. It is the man's own symbol – his soul's picture, in a word – the sign which belongs to him and to no-one else. Who can give a man this, his own name? God alone, for no one but God sees who the man is. |

C. S. Lewis understood this, too. When Mercury descended to earth in The Descent of the Gods in that chapter in That Hideous Strength, here's how he described it:

It was as if the words spoke themselves through him from some strong place at a distance – or as if they were not words at all, but the present operations of God. For this was the language spoken before the Fall and beyond the Moon and the meanings were not given to the syllables by chance, or skill, or long tradition, but truly inherent in them, as the shape of the great Sun is inherent in the little water-drop. This was Language herself, as she first sprang at Maleldil's bidding out of the molten quicksilver of the star called Mercury on Earth but Viritrilbia in Deep Heaven. [7]

The most important proper name to you is your own. In C. S. Lewis's Anthology of 365 Selections from George MacDonald, the one most readers find the most powerful and the most unforgettable is MacDonald's commentary on Revelation 2, verse 17 ("And I will give him a white stone, with a new name written in it, that no-one knows save he who receives it."): Here is MacDonald's commentary on that, and I think this deeply influenced Tolkien, who also loved MacDonald's spirit, though not his style:

The giving of the white stone with the new name is the communication of what God thinks about the man to the man. It is the divine judgement, the solemn holy doom of the righteous man, the "Come, thou blessed," spoken to the individual. The true name is one which expresses the character, the nature, the meaning of the person who bears it. It is the man's own symbol – his soul's picture, in a word – the sign which belongs to him and to no-one else. Who can give a man this, his own name? God alone, for no one but God sees who the man is.

Hamlet has an identity crisis until he knows Shakespeare.

It is only when the man has become his name that God gives him the stone with the name upon it. For then first can he understand what his name signifies. God's name for a man must be his expression of His own idea of the man, that being whom He had in His thought when He began to make the child, and whom He kept in His thought through the long process of creation that went to realize the idea. To tell the name is to seal the success – to say, "In thee also I am well pleased." [8]

Finally, the most magical language is music – a word about music in Tolkien. Music is clearly the language of creation; God and his angels sing the world into being. Tolkien begins The Silmarillion this way: "In the beginning, Eru, The One, who in the Elvish tongue is Illuvatar (All-Father) made the Ainur of his thought; and they made a great Music before him. In this Music the World was begun." [9] Notice it's not that music was in the world, but that the world was in music. This is the "music of the spheres", in which everything is. This is the "Song of Songs" that includes all songs. All matter, all time, all space, all history – all are in this primal language. Plato knew the power of music. In The Republic, music is the very first step in education in the just society, and the very first step in corruption in the bad one. Nothing is more important to the good society, to education, to happiness.

The Lord of the Rings is full of music, full of music. One of the indices at the end of The Lord of the Rings lists songs or poems in the book. Proper names, yes. Places, yes. But songs or poems? There are so many that he needs an index. The hobbits sing high hymns to El-Bereth, and walking songs, and bath songs. Like Tolkien, Bombadil is a writer of prose who is bursting with poetry and music. Peter Beagle, in the introduction to A Tolkien Reader, calls him, "a writer whose own prose is itself taut with poetry." [10] I think music is an essential part of the Elvish enchantment. When the Fellowship enters Lothlorien, Sam says, "I feel as if I was inside a song, if you take my meaning." And that's how we feel when we enter this whole book.

Endnotes:

- J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1994), p. 139.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 191.

- Ibid., p. 193.

- Ibid., p. 704.

- Ibid., p. 712.

- C. S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength (New York: Macmillan, 1965), p. 319.

- C. S. Lewis, ed., George MacDonald: An Anthology (New York: Macmillan, 1978), pp. 7-8.

- J. R. R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion (London: HarperCollins, 1977), p. 25.

- J. R. R. Tolkien, The Tolkien Reader (New York: Ballantine Books, 1966), Foreward: "Tolkien's Magic Ring", p. xv.

Read part 1 of this talk here.

Read part 2 of this talk here.

Read part 3 of this talk here.

Read part 4 of this talk here.

Read part 5 of this talk here.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Peter Kreeft. "Language of Beauty – part 5: The Power of Names" transcribed from a talk given at Trinity Forum Academy (June 6, 2005).

This talk based on ideas contained in Peter Kreeft's book The Philosophy of Tolkien.

This article is reprinted with permission from Peter Kreeft.

The Author

Peter Kreeft, Ph.D., is a professor of philosophy at Boston College. He is the author of many books (over forty and counting) including: Ask Peter Kreeft: The 100 Most Interesting Questions He's Ever Been Asked, Ancient Philosophers, Medieval Philosophers, Modern Philosophers, Contemporary Philosophers, Forty Reasons I Am a Catholic, Doors in the Walls of the World: Signs of Transcendence in the Human Story, Forty Reasons I Am a Catholic, You Can Understand the Bible, Fundamentals of the Faith, The Journey: A Spiritual Roadmap for Modern Pilgrims, Prayer: The Great Conversation: Straight Answers to Tough Questions About Prayer, Love Is Stronger Than Death, Philosophy 101 by Socrates: An Introduction to Philosophy Via Plato's Apology, A Pocket Guide to the Meaning of Life, Prayer for Beginners, and Before I Go: Letters to Our Children About What Really Matters. Peter Kreeft in on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Peter Kreeft, Ph.D., is a professor of philosophy at Boston College. He is the author of many books (over forty and counting) including: Ask Peter Kreeft: The 100 Most Interesting Questions He's Ever Been Asked, Ancient Philosophers, Medieval Philosophers, Modern Philosophers, Contemporary Philosophers, Forty Reasons I Am a Catholic, Doors in the Walls of the World: Signs of Transcendence in the Human Story, Forty Reasons I Am a Catholic, You Can Understand the Bible, Fundamentals of the Faith, The Journey: A Spiritual Roadmap for Modern Pilgrims, Prayer: The Great Conversation: Straight Answers to Tough Questions About Prayer, Love Is Stronger Than Death, Philosophy 101 by Socrates: An Introduction to Philosophy Via Plato's Apology, A Pocket Guide to the Meaning of Life, Prayer for Beginners, and Before I Go: Letters to Our Children About What Really Matters. Peter Kreeft in on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.