The consolations of fantasy

- NIC ROWAN

On "Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth" at The Morgan Library & Museum.

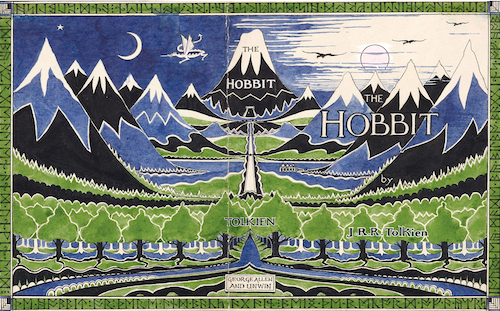

The original cover for The Hobbit, illustrated by J. R. R. Tolkien

The original cover for The Hobbit, illustrated by J. R. R. Tolkien Photo: The Morgan Library & Museum.

"In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit." J. R. R. Tolkien said the first sentence of The Hobbit came to him out of nowhere, and the rest of the book's adventures unfolded from there. The novel reads like a series of bedtime stories, and intentionally so: Tolkien originally devised the tales in The Hobbit to entertain his own four children.

The Morgan Library & Museum presents a similar view of Tolkien in"Maker of Middle-earth," on view through May 12. Visitors enter through a hallway adorned with a mural-sized reproduction of Tolkien's original illustration of Bilbo's hobbit hole and explore a collection of the author's illustrations, correspondence, and writings. Originally on view at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England, last year, "Maker of Middle-earth" fills out the typical picture of the man so well known for The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion. Above all else, the exhibition casts Tolkien as a father and a linguist—and only later as a fantasy writer.

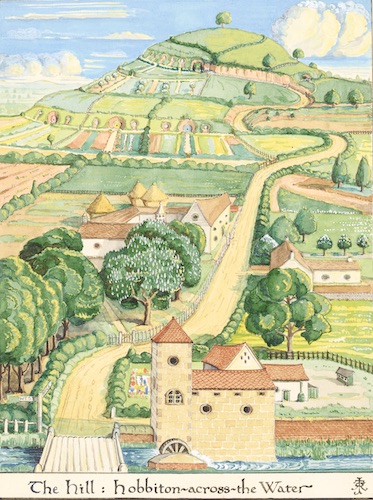

One of J. R. R. Tolkien's illustrations for The Hobbit.

One of J. R. R. Tolkien's illustrations for The Hobbit. Photo: The Morgan Library & Museum.

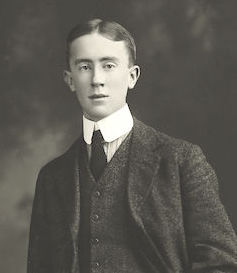

The exhibition opens with a series of photographs and drawings from Tolkien's childhood in South Africa and then moves to letters from his early romance with Edith Mary Bratt (when they met he was sixteen, his future wife nineteen) and his service in the first World War. Throughout his young life, Tolkien wrote and illustrated early versions of his mythology, displaying a fascination with the roots of the English language before it was disrupted and Latinized by the Norman invasion in the eleventh century.

J. R. R. Tolkien at age nineteen.

J. R. R. Tolkien at age nineteen.Photo: The Morgan Library & Museum.

Tolkien used ancient languages of the North, especially Old English and Finnish, as the basis for his two Elvish languages: "The invention of language is the foundation," he wrote of his novels. "The 'stories' were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse."

Ancient words from real languages mix with Tolkien's new words from his invented languages to marry the actual with the fantastical, the old with the new.

In a notable example, he drew the name of the wandering mariner Earendel, who sails into the sky in The Silmarillion, from earendel, or morning star, an Old English word that he found in the devotional poem "Christ I," by an anonymous ninth-century author. Ancient words from real languages mix with Tolkien's new words from his invented languages to marry the actual with the fantastical, the old with the new.

As he delved deeper into language, Tolkien also began creating stories for his children. The exhibition includes original manuscripts and illustrations from his Letters from Father Christmas, an annual update sent to his children on Christmas Day from 1920 to 1942. The most touching of the illustrations, however, is not from the Father Christmas collection. It's a standalone painting of an owl Tolkien made to help his young son Michael overcome his fear of an owl he had seen in his dreams.

An annual update from Father Christmas to J. R. R. Tolkien’s children

An annual update from Father Christmas to J. R. R. Tolkien’s childrenPhoto: The Morgan Library & Museum.

Juggling raising a family and teaching at Oxford put Tolkien's creative output at a premium. "Writing stories in prose or verse has been stolen, often guiltily, from time already mortgaged," he said of writing stories for his children.

Tolkien was able to do much with stolen time. The exhibition displays a series of maps, watercolors, and ink illustrations that display the full breadth of his skills as an artist.

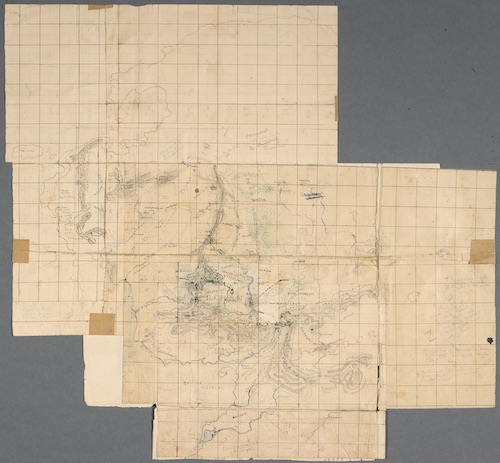

Yet Tolkien was able to do much with stolen time. The exhibition displays a series of maps, watercolors, and ink illustrations that display the full breadth of his skills as an artist. This includes the original covers that he illustrated for the Lord of the Ringsnovels and The Hobbit. Alongside these are Tolkien's detailed maps of Middle-earth, where he blended his love for language and illustration with detailed topographies and elvish script. But even more amusing than these illustrations—which are already familiar to fans from their numerous reprints in his novels—are the newspapers on which he doodled in the style of illuminated manuscripts. These were products of Tolkien's restless mind, many made while presiding over classes at Oxford.

R. R. Tolkien's first map for Lord of the Rings.

R. R. Tolkien's first map for Lord of the Rings.Photo: The Morgan Library & Museum.

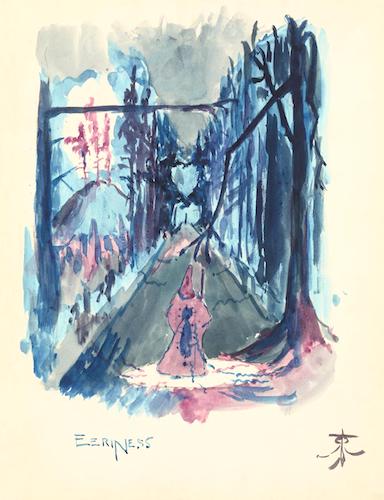

A number of Tolkien's other illustrations are also striking, such as Eeriness, a January 1914 ink drawing depicting a hooded figure walking into the woods, covered with deep purple undergrowth—almost like a proto-Gandalf wandering into Mirkwood. And it very well may be. According to his son Christopher Tolkien, he saved "a very high proportion of everything he ever wrote," not only out of habit, but because his old ideas were inevitably the wells from which he drew new ones.

. Eeriness, an ink drawing by J. R. R. Tolkien

. Eeriness, an ink drawing by J. R. R. TolkienPhoto: The Morgan Library & Museum.

Notably absent in "Maker of Middle-Earth" is any reference to Peter Jackson's film adaptations of either the Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit. No appeals to fanboys and fantasy nerds here. The Morgan also refrains from playing Howard Shore's tin-tuned film score in the background—restraint the Met should have exercised before putting the "Ave Maria" on endless loop at the "Heavenly Bodies" exhibition this past summer.

And so much the better. The exhibition invites its viewers to understand Tolkien, not as a writer who sought to escape reality, but as one who sought to reveal the world through myths of his own making. Tolkien expressed the same conviction in the conclusion to his essay "On Fairy Stories": "The peculiar quality of the 'joy' in successful Fantasy can thus be explained as a sudden glimpse of the underlying reality or truth. It is not only a 'consolation' for the sorrow of this world, but a satisfaction, and an answer to that question, 'Is it true?' "

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Nic Rowan. "The consolations of fantasy." The New Criterion (February 27, 2019).

Nic Rowan. "The consolations of fantasy." The New Criterion (February 27, 2019).

Reprinted with permission of The New Criterion and the author, Nic Rowan.

The Author

Nic Rowan is a media analyst at the Washington Free Beacon. His work has also appeared in the Wall Street Journal, First Things, and The New Criterion.

Copyright © 2019 The New Criterion