Giovanni Bellini: A Shared Moment of Transformation

- LANCE ESPLUND

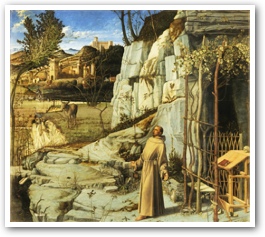

In 1912, Mrs. Bernard Berenson, the wife of the famed Renaissance art scholar, described Giovanni Bellini's "St. Francis in the Desert" (c. 1480) as "the most beautiful Bellini in existence, the most profound and spiritual picture ever painted in the Renaissance."

|

Giovanni Bellini's "St. Francis in the Desert"

|

And ever since Henry Clay Frick acquired the painting in 1915, it has remained one of the highlights of the Frick Collection.

Yet it is also among the most metaphorically rich, complex and unusual Italian Renaissance paintings in America. Its title – which locates St. Francesco Bernardone of Assisi (c. 1182-1226), the founder of the Franciscans, in the desert – throws into strong relief the picture's lush Tuscan setting. St. Francis took vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, distinguished by three knots in his rope girdle. He recreated the first nativity, preached to the animals and tamed wild beasts. The "desert" probably refers to the wilderness of Mount La Verna in the Apennines, where, in 1224 during a solitary retreat, St. Francis is believed to have been the first person to receive the stigmata, or the imprint of the five primary wounds of Christ's crucifixion.

In March, the painting was sent to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for minor cleaning and microscopic, high-tech analysis by conservators, art historians and scientists. Their discoveries – including Bellini's compositional changes, surprisingly bravura brushwork, fingerprints and underdrawing, as well as the revelation that he anticipated some of the innovations attributed to his greatest students, Giorgione and Titian – are the focus of the Frick's boutique show "In a New Light: Bellini's 'St. Francis in the Desert.'"

Organized in conjunction with the Met's Paintings Conservator Charlotte Hale by Susannah Rutherglen, Andrew W. Mellon Curatorial Fellow at the Frick, and Lisa Candage, the museum's New Media specialist, "In a New Light" inaugurates the Frick's Multimedia Room. Located off the Garden Court and mere steps away from Bellini's masterpiece, the room allows visitors to consult computers and watch related videos. (The show runs from May 22 through Aug. 28.)

Technology-driven exhibitions of this kind tend to emphasize information about an artwork and the artist's process at the expense of the aesthetic experience one gets from looking at the original. But this show is different. For one thing, many of the findings presented in the Multimedia Room add to our understanding of the painting's iconography, thus deepening the experience of looking. These include the presence of the nearly invisible wound of the stigmata on St. Francis's foot; and the confirmation that, long after Bellini's death, the painting was trimmed. Only a few centimeters along its top edge were removed, a trim that disposes of a long-held theory that the picture may have been large enough to include heavenly figures. Best of all, however, "In a New Light" moves Bellini's painting to the Frick's skylit Oval Room. For the first time in nearly a century, "St. Francis in the Desert," bathed in natural light and freed from its shadowy existence in the Frick's Living Hall, can breathe, and reveal secrets available to the naked eye.

Unlike other versions of St. Francis, Bellini's does not highlight the stigmatization. Traditional representations of this subject show the crucified Christ with the wings of a seraphim appearing in a vision before the kneeling St. Francis and inflicting the wounds on the saint's hands, feet and side. In his version, Bellini depicts St. Francis by himself, the primary allusion to the painting's subject being his upward gaze and outward-facing palms. The picture's elastic space pulls faraway objects forward and rises vertically as much as it recedes, creating the sense of transformation and an ever-opening world. In departing from the traditional representation of St. Francis's "vision," Bellini conveys the sense that we are experiencing a vision ourselves.

At roughly 4 feet tall by 4½ feet wide, Bellini's oil on panel is large, but not too large; natural yet dramatic. The painting overflows with symbols relating to, among others, Moses, the Virgin, St. John the Baptist, the Immaculate Conception and the Eucharist. Yet the painting is also among the first and largest naturalistic landscapes in Western art.

|

Bellini (c. 1430-1516), working with the new medium of oil paint, depicts St. Francis in the lower right of the picture standing outside his hut, his figure anchoring the creamy celadon and golden-green landscape. The foreground is dominated by a rocky, mossy cliff-face and darkened cave, outside of which is an arbor, or study, topped by twisting grapevines. Inside are the saint's attributes: a desk, a holy book, a hermit's skull, a reed cross and a crown of thorns. Though stony, the landscape feels far from barren. And its prevailing color speaks not of an arid environment, but one ripe with possibility. The painting's middle and background include a walled hill town; rolling, cultivated fields; a river and footbridge; a donkey, a gray heron, and a shepherd tending his grazing flock. Some of these forms feel autumnal yet transformed by a sudden spring.

The sky is active, crystalline and brilliant blue. Light pours prodigiously from the upper left and knifes its way into the landscape, prying it open. Yet the entire painting feels lit from within, as if light were radiating from the rocks and fields. It is as if lightning had just struck; as if the whole world were receiving the stigmata. St. Francis, barefoot, cloaked in his brown habit, perhaps having just emerged from his cave, stands with arms outstretched, head lifted and chest heaving, gazing toward heaven. His world undergoes a metamorphosis: The very rocks surrounding him pool, shifting from solid to liquid. St. Francis, no less than the viewer, is hit by the wave-like force of the painting's otherworldly light. And like a lightning rod he absorbs and disseminates it into the landscape.

Bellini doesn't merely depict a scene from the saint's life. Rather, he creates a work of art that conveys in its entirety a sense of transformation. Like the stigmata St. Francis received, Bellini's picture is an empathetic, physical manifestation of the mystical – an opportunity for us to share in the rapture.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Lance Esplund. "A Shared Moment of Transformation." The Wall Street Journal (May 21, 2011).

Reprinted with permission of the author and The Wall Street Journal © 2011 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Author

Lance Esplund is senior art critic for CityArts Magazine and a regular contributor to The Wall Street Journal, where he writes the biweekly "Fine Art" column. From 2004-2008 he was chief art critic of The New York Sun. He has written numerous museum and gallery exhibition catalog essays and has contributed essays and reviews (some of which have been anthologized) to many journals. He is an adjunct associate professor at Rider University and has taught at, among other schools, the Kansas City Art Institute, Queens College CUNY, and the Parsons School of Design, where he served on the faculty from 1989-2004. In September 2011, he will join the faculty of the New York Studio School.

Copyright © 2011 Wall Street Journal