The Secularization of the Supreme Court

- JAMES HITCHCOCK

American courts are taking a steadily more suspicious attitude toward religious interests, and the trend is likely to continue unless Catholics and their allies take a keen interest in future judicial appointments.

|

American Catholics often consider the US Supreme Court unfriendly to their interests, primarily because of abortion and a long series of decisions forbidding public aid to Catholic schools. However, prior to World War II Catholics triumphed in many of the cases they brought before the Court — even though anti-Catholicism was stronger during earlier periods of American history. The post-war reversal was made possible partly by the political naïveté and immaturity of Catholics themselves.

The

most important of the earlier cases was Pierce v. Society of Sisters

(1925), in which the Court invalidated an Oregon law requiring all children to

attend public schools. It was a landmark decision because it formally recognized

the right of religious schools to exist. As late as 1930 the Court upheld a state

program providing textbooks for Catholic schools, the last in a series of cases

in which public aid to religious institutions was found to be constitutional.

Catholic success before the Supreme Court had little to do with any Catholic presence

on the Court; all the favorable decisions were rendered by Protestant justices.

Whatever their personal opinions, most of the justices prior to 1947 appear to

have weighed Catholic claims with judicious fairness.

The

Klansman on the Court

The revolutionary change in the Court began in the 1930s, when, stung by decisions which struck down some of the economic legislation of the New Deal, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began to choose justices inclined to approach the Constitution in a "broad" and "flexible" spirit. A Court chosen to embody this philosophy regarding economic questions espoused the same general theory on other questions as well, and an unforeseen result of Roosevelt's transformation of the Court was a new approach to religion. Some of Roosevelt's appointees were crudely anti-Catholic.

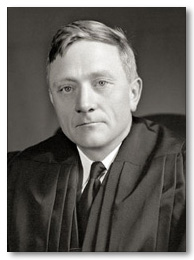

Hugo L. Black (who served on the Court from 1937 to 197l) was a lapsed Baptist who had little use for organized religion of any kind but, like many ex-fundamentalists, retained anti-Catholicism as perhaps the sole legacy of his former faith. His nomination to the Court was almost derailed when it was revealed that he had belonged to the Ku Klux Klan. He repudiated the Klan's racism but not its anti-Catholicism, and his son said that the one thing Black retained in common with the Klan was his suspicion of the Catholic Church. Black gave lectures before Klan groups, exposing what he considered to be the evils of the Catholic Church, and considered Governor Alfred E. Smith of New York unqualified for the Presidency in 1928 because of his Catholicism.

As a lawyer in Alabama, Black had successfully defended a Methodist minister who shot and killed a Catholic priest in front of witnesses, because the priest had officiated at the marriage of the minister's daughter to a Puerto Rican. The future Supreme Court justice fought the case with unusual aggressiveness, peppering his courtroom oratory with anti-Catholic comments.

Black, a Mason, was offended by the fact that the Catholic Church condemned Masonry, whose adherents he characterized as "free-thinkers." In effect he did not think Catholic schools had the right to exist; he thought the Pierce case had been wrongly decided and did not want it to be cited as a precedent. In the seminal Everson case (1947), Justice Black allowed the government to reimburse parents for the cost of transporting their children to religious schools. Privately, however, he confided that he had rendered the decision for strategic purposes only, and in that case he laid down, for the first time, the modern Court's claim that strict separation was the intention of the Framers of the Constitution. Black periodically issued thinly veiled cautions against the Catholic menace. He warned: "The same powerful sectarian propagandists who have succeeded in securing passage of the present law can and doubtlessly will continue their propaganda, looking towards complete domination and supremacy of their particular brand of religion."

Douglas and Frankfurter

|

William

O. Douglas (1898-1980) |

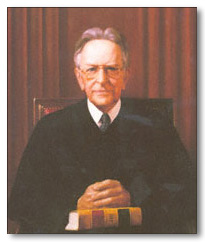

William O. Douglas (who served on the Court from 1939 to 1975) was the son of a Presbyterian minister but grew up with the belief that respectable church-going people were "not only a thieving lot, but hypocrites, and above all else dull, pious, and boring." He claimed to have abandoned belief in heaven and hell because he said that he could not stand the prospect of spending eternity with people like Cardinal Francis J. Spellman of New York.

Although Douglas professedly believed in the strictest separation of church and state, in fact he used his judicial authority to promote his own theological opinions. He characterized the Bible as "a dangerously subversive document for authoritarian governments" and judged religion exclusively in terms of whether it supported "progressive" social causes, warning that the wealth of the churches could lead to violent revolution.

Religion, he concluded, was essentially used to control people. But he identified pockets of religious progressivism amidst what he considered to be a sea of exploitation, and made Catholic priests into both villains and heroes. When bishops in Puerto Rico criticized a candidate for governor, Douglas denounced their action a clear violation of the Constitution; but in 1967, when Father Charles Curran of the Catholic University of America publicly rejected the Church's teaching on birth control, Douglas wrote to congratulate him "in the name of the First Amendment community."

One of Douglas' problems with the Catholic schools involved his own version of political correctness; he feared that Catholic history texts would not deal properly with the Crusades, the Spanish conquest of Mexico, or the Franco government in Spain. ("I can imagine what a religious zealot, as contrasted to a civil libertarian, can do with the Reformation or with the Inquisition.") He once warned Black that "I think if Catholics get public money to finance their schools, we better insist on getting some good prayers in public schools or we Protestants are out of business."

Felix Frankfurter occupied the "Jewish seat" on the Court from 1939 to 1962, although he described himself as "a reverent agnostic." He first devised the formula that the majority of the Court has implicitly followed for decades: religious believers should enjoy full liberty under the Constitution only so long as they accept their faith as purely personal and refrain from making claims about its truth. Frankfurter denounced the Court's religious critics as guilty of a "filthy, dirty, smearing technique," but he tacitly admitted the validity of their criticisms by insisting that the public schools should indeed be dominated by "secularism."

The

"Catholic seat"

From 1894 through the era of the New Deal, there was always at least one Catholic on the Court, and Roosevelt honored the tradition by appointing Francis P. Murphy, a man who had a paradoxical relationship to Catholicism: ostentatious piety on the one hand (he was a Third Order Franciscan), suspicion of the Church as an institution on the other. Murphy, who served from 1940 to 1949, was the original paradigm of the way in which John F. Kennedy would deal with "the religion issue" a generation later. Like Kennedy, Murphy adopted a view of the separation of church and state that seemed to suggest merely that religious principles should make no inconvenient demands on politicians. Also like Kennedy, he enjoyed the confidence of bishops who never questioned his politics; Cardinal George J. Mundelein of Chicago, a strong supporter of the New Deal, called him "a lay bishop." For a time Justice Murphy was on good terms with the influential "radio priest" Father Charles Coughlin and at one point acted as Roosevelt's emissary in an unsuccessful attempt to reverse Coughlin's opposition to the New Deal. At Roosevelt's request, Murphy appeared before the Knights of Columbus to defend the American policy of the "lend-lease" of war materials to the Soviet Union, which the Vatican opposed.

Murphy never attended a Catholic school at any level, but claimed to have been influenced by Jacques Maritain and by modern popes — although none of his public statements manifested any theological or philosophical sophistication. He thought American democracy reflected the divine will and that a "higher law" should govern the interpretation of the Constitution, characterizing this belief as a combination of "the Goddess of Reason [of the French Revolution] and the Sermon on the Mount." For Murphy, religious belief shaded almost completely into liberal politics. He regarded his various public offices as an exercise in "practical Christianity" and embraced a goal "which, in a sense, is larger, more vital, than religion itself...the fulfillment of the ideal of democracy in its every phase."

Prior to being called to Washington, Murphy — perhaps without knowing it — was made to pass a religious test. He was recommended to Roosevelt by the latter's brother-in-law, who told the President that Murphy was a Catholic "who will not let religion stand in his way," and the future justice himself assured a Roosevelt advisor that he kept religion and politics "in air-tight compartments." But, although usually inclined to discount anti-Catholicism, Murphy later came to believe that that he was a victim of a cabal in the White House which prevented Catholics from gaining high positions in the war effort.

Some of Murphy's brethren on the Court continued to hold him to a religious test, and to some extent he internalized the test. Frankfurter said of him, condescendingly, "When I think of the many Catholics that have taken the life of dissenters, I'm not surprised that F.M. wants the undivided glory of being a dissenter," and privately Murphy admitted, "It comforts me that with eight hundred years of Catholic background I can speak in defense of a people opposed to my own faith."

Murphy considered abstaining in the Everson case, but ended by supporting the decision. Frankfurter, however, strongly pressed him to dissent, using tactics little short of moral blackmail, playing on Murphy's evident craving for approval by people who did not respect his faith. ("For the sake of history, for the sake of your inner peace, don't miss," Frankfurter urged, exhorting Murphy to rise above "flattery," "false friends," and "temporary fame" and to look to his place in history.) In connection with the McCollum case (1948), which first applied the theory of absolute separation of church and state, Justice Wiley Rutledge said of Murphy, "He was in a very hard spot, but that didn't keep him from coming through 100 percent."

Murphy's most remarkable opinion, in light of his Catholicism, was his dissent in the Cleveland case (1946), in which the Court reaffirmed the legal ban on polygamy. Justice Douglas (who would eventually go through three marriages) wrote a stinging condemnation of the practice, while the bachelor Murphy argued that polygamy might enjoy a legal status midway between marriage and fornication. Following Murphy's death in 1949, a fellow Catholic, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath, eulogized him as "a devout Roman Catholic, who disregarded personal preferences which we all know were very dear to him, in favor of what his conscience told him to be his duty as justice of this Court," a formula in which moral law was reduced to "personal preference" and "conscience" served the needs of political expediency — an early formulation of what would become the Kennedy Doctrine.

New

precedents

Robert H. Jackson, a nominal Episcopalian, was extraordinarily blunt in revealing his own prejudices: "Our public school, if not a product of Protestantism, at least is more consistent with it than with the Catholic culture and scheme of values."

Rutledge, the lapsed son of a fundamentalist Baptist minister, was one of the founders of the new separationist jurisprudence. Prior to the Everson decision he circulated a warning to his brethren that the Catholic Church was planning "a raid on the treasury."

Although the Court in 1947-1948 claimed merely to be interpreting the Constitution in the way it had always been intended, the majority actually ignored some of the precedents that went against this claim, and regularly misstated those precedents which they did cite. In a moment of candor Douglas approvingly quoted an earlier justice: "At the constitutional level where we work, 90 percent of any decision is emotional. The rational part of us supplies the reasons for supporting our predilections" — a belief to which Frankfurter and Rutledge also subscribed. Logically, therefore, the Court in the 1940s was free to interpret the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment in almost any way it chose.

The Supreme Court's anti-religious

bias can be traced to the personal histories of the men sitting on the Court in

1947. For probably the first time in its history, the Court was composed of a

majority who had come to believe that the faiths in which they had been raised

were false and even pernicious: Black and Rutledge, Baptists who had moved towards

Unitarianism; Douglas, a disgruntled Presbyterian; Frankfurter, a secular Jew;

Jackson, raised by parents who despised the emotional religiosity of their neighbors;

Murphy, a liberal Catholic who thought that his Church had too much power. Ironically,

Justice Stanley Reed, the only member of the Court to question the new separationism,

appears to have belonged to no church.)

The

anti-Catholic Catholic

|

Former

Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun, author of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision |

When Justice Murphy retired in 1949, President Harry S Truman declined to accept the claim of a "Catholic seat" on the Court, and the period 1949-1956 marked the only time since 1894 that no Catholic served on the country's highest court. Truman named Tom C. Clark, a Presbyterian whose chief importance lies in the fact that in the 1960s he redefined religion in the broadest possible way: "a sincere and meaningful belief which occupies in the life of its possessor a place parallel to that filled by God [in the lives of others]." Although some people thought religion had to emanate "from a superior source," Clark held that such was not a tenable principle under the Constitution.

In 1956 President Dwight D. Eisenhower was persuaded that a Catholic should be appointed to the Court, and a search produced the name of William J. Brennan, a justice of New Jersey's highest court, who would remain on the Supreme Court until 1990. Cardinal Spellman was consulted, and confirmed that Brennan was a practicing Catholic. But an acquaintance said of Brennan, "Those who knew him realized that, although he was a decent person and God-fearing, he was not a zealously religious man. He was Catholic with a small 'c.'" Thus Eisenhower's wish to please Catholics by naming one of their own to the Court led, ironically, to the appointment of a man who would use his power to undermine Catholic interests at every point.

During his confirmation hearings Brennan gave another preview of the "Kennedy Doctrine" when he was asked whether his allegiance to the pope would outweigh his allegiance to his country; he replied that nothing could take precedence over his patriotic duties. Some Catholics criticized his answers, but several bishops endorsed him.

Brennan was one of the most influential justices in the history of the Court, and the strictest of separationists. His position seems to have been motivated in part by his liberal religious outlook and his estimate of the effect separationism might have on his Church. Apparently he both expected and desired that many Catholic schools would be closed, while the rest would lose their religious identities. Thus he once assured his brethren:

If public funds are not given, parochial schools will not perish. Two winds are blowing: (a) in the United States, education is no business of Catholics; and (b) it won't be many years until Notre Dame is like Harvard, etc.

Brennan objected to state-supported remedial-education programs in Catholic schools on the grounds that "...they serve the principal purpose of integrating the child, both socially and educationally, into the parochial school. Such services foster in the child a profound dependence on the religious school..." Brennan believed that the public schools were a uniquely unifying force, because they were based on "democratic values," while private schools were not.

Brennan, who proved to be unwaveringly

pro-abortion, never once issued a favorable opinion in a case of concern to his

fellow Catholics. But he once made a passionate, albeit unsuccessful, plea for

the Court to make sweeping modifications in the laws of property, in order to

accommodate the beliefs of American Indians.

Religion

on the defensive

|

Former

Supreme Court Justice Byron R. White, a Kennedy appointee who dissented from the Roe v. Wade decision. |

Of other Eisenhower appointees, John Marshall Harlan III was an Episcopalian generally favorable to religious interests, while Potter Stewart, also an Episcopalian, appears to have been somewhat anti-Catholic, in that he consistently voted to accommodate religious practices in the public schools but equally consistently opposed public aid to Catholic schools. When the Court upheld grants to religiously affiliated colleges, Stewart objected that theology was not an academic subject.

Democratic appointees have almost always been strict separationists, the major exception being a Kennedy appointee, Byron R. White (1962-93), also an Episcopalian.

When Frankfurter retired, Kennedy appointed Arthur Goldberg to the "Jewish seat" on the Court, and, when Goldberg resigned in 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson named Abe Fortas. Goldberg and Fortas were both strict separationists. President Richard M. Nixon rejected the idea of a Jewish seat, and after 1969 no Jew sat on the Court for almost a quarter of a century.

During his brief time on the Court (1965-1969), Fortas was the first to articulate a tenet of separationist jurisprudence which effectively places religious believers permanently in a defensive posture, when he held that in public schools believers have no right to protection from views which are distasteful to them, even though non-believers must be shielded from unwelcome religious ideas.

As a presidential candidate Nixon proclaimed a Republican intention to reverse the Supreme Court's liberalism, but his efforts in the White House produced only indifferent results.

Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, a Presbyterian, was sometimes an accommodationist, allowing some forms of public religious expression and some forms of public aid to private schools. But his Lemon decision (1971) laid down a test for public programs as they impinged on religion — a test which, as it turned out, few programs could pass. Burger also came close to disenfranchising religious believers, when he claimed that the Constitution intended to inhibit public controversy of a religious nature, a claim from which he later backed away.

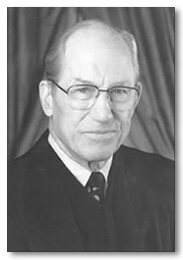

Harry Blackmun, a Methodist,

became the author of the infamous Roe v. Wade decision finding a constitutional

"right" to abortion. He was also a consistent liberal on religious issues, as

was another Nixon appointee, Lewis F. Powell, a Presbyterian.

The

current court

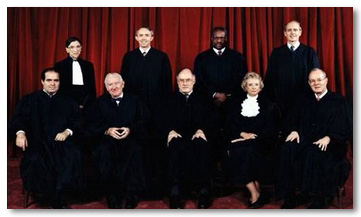

|

The

current makeup of the US Supreme Court: (back row from left) Ruth Bader Ginsburg, David H.. Souter, Clarence Thomas and Stephen Breyer, (front row from left) Antonin Scalia, John Paul Stevens, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, Sandra Day O'Connor, and Anthony M. Kennedy. |

But William H. Rehnquist (an Associate Justice from 1972 to 1986, then Chief Justice to the present day), a Lutheran, has been by far the most important conservative on the modern Court in terms of religious issues, upholding most forms of public religious expression and aid to religious education and opposing legalized abortion. He was also the first justice to attempt a systematic refutation of the separationist philosophy that has prevailed on the Court since 1947.

President Gerald R. Ford appointed John Paul Stevens, who is apparently without formal religious affiliation. An unwavering separationist, Stevens sees opposition to abortion as essentially religious, so that there can be no legal restrictions on the practice. He has also questioned whether private religious education is good for the nation.

Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman on the Court and the first justice named by President Ronald Reagan, is an Episcopalian. She is an influential "swing vote" in religion cases and often determines which side will prevail. She has expanded Clark's secular redefinition of religion, describing its purpose as merely "the solemnization of public occasions" and "expressing hope for the future."

Reagan also appointed Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy. Scalia, along with Rehnquist, has been a severe critic of the modern Court's approach to constitutional issues. In a public address in 2002, he disagreed with Catholics, including Pope John Paul II, who oppose capital punishment and asserted that judges who do not support the death penalty should resign from the bench. Kennedy, like O'Connor, tends to occupy the ideological middle of the bench. But in the Romer case (1996) he issued an opinion of far-reaching implications, when he proclaimed a constitutional "right of self-definition" in connection with homosexuality.

|

Supreme

Court Justice Clarence Thomas returned to the Catholic faith of his childhood in 1996. |

In 1990, President George H.W. Bush appointed Clarence Thomas, a black Episcopalian who had been raised a Catholic, studied for the priesthood, then left the Church for many years. In 1996 Thomas announced that he had returned to the Church. He is often allied with Rehnquist and Scalia and has vigorously argued that the Court's understanding of the Establishment Clause since 1947 is fundamentally in error. In a case in 2000, Thomas bluntly traced the separationist position to historic anti-Catholicism and called it "a shameful pedigree." But Bush also named David Souter, an Episcopalian who is a strict separationist and a passionate defender of abortion "rights."

President William J. Clinton became the first Democratic president in over a quarter of a century able to name a member of the Court, and he chose two liberal Jewish justices: Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer.

Indicative of changing

political alliances, the Republican ascendancy in the White House in 1988 produced,

for the first time in history, three Catholics sitting on the Court simultaneously:

Brennan, Scalia, and Kennedy, with Thomas later replacing Brennan as part of a

Catholic triumvirate. Through much of its history the Court was an entirely Protestant

body, but Protestants are now a minority.

Will

Catholics respond?

The judicial revolution of the 1940s, which has had a deep and continuing effect on American life, would not have been possible without a certain Catholic political passivity, because of which the Church has far less influence than its numbers warrant. Catholics were an indispensable part of the New Deal coalition, but they made no sustained and effective effort to influence judicial appointments.

Thus, despite his blatant bigotry, there was no significant Catholic opposition to Black's nomination, just as there was no protest against Truman's refusal to name a Catholic to the Court. Murphy was able to present himself as a devotee of Catholic social doctrine, even though he seemed to accept the idea that Catholics had continually to prove themselves to those hostile to their faith.

|

Supreme

Court Justice Antonin Scalia |

Despite the outrageous public comments of Black and Douglas, Catholics during the post-war period were unable (or unwilling) to bring pressure to bear on the Democratic Party to select better justices, and, when a Republican president gave them an opportunity in 1956, the Church's leadership could not identify a candidate able to bring to bear a truly Catholic perspective on the great issues of the day, and they readily acquiesced in Brennan's appointment. Largely because of Catholic political naïveté and loyalty to the Democratic Party, the Court after 1947 could steadily exclude religion from public life.

Justice Murphy's claim to follow papal social teachings — which somehow did not prevent him from justifying polygamy — helps to explain this passivity. Many Catholics were led to believe that those teachings amounted almost exclusively to an affirmation of the welfare state, and they seemed not to understand, or perhaps to care about, the great moral issues involved in the Court's treatment of education and, eventually, of matters like abortion.

With few exceptions, Democratic nominees to the Court since the 1930s have been reliably liberal, while Republican nominees have not been predictably conservative, a pattern attributable, among other things, to the fact that, as recently as the administration of the first President Bush, "mainstream" Republicans themselves did not fully understand (or care about) the nature of the judicial revolution. Catholics and other religious believers have at last awakened to its reality, but whether almost a half-century of aggressively secularist constitutional interpretation can now be overcome is entirely dependant on future appointments to a Court poised between two irreconcilable views of the nation's founding document.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

James Hitchcock. "The Secularization of the Supreme Court." Catholic World Report (April, 2004): 46-51.

This article is reprinted with permission from Catholic World Report.

Catholic World Report is a monthly news magazine covering international news from a distinctly Catholic perspective. Read and quoted by top Church leaders and other publications, CWR not only reports on important events in the Church, it helps shape them. CWR has been at the forefront in public debates about clerical abuse, liturgical renewal, the Eastern churches, and threats to religious freedom.

Catholic World Report also publishes Catholic World News.

The Author

James Hitchcock, historian, author, and lecturer, writes frequently on current events in the Church and in the world. Dr. Hitchcock, a St. Louis native, is professor emeritus of history at St. Louis University (1966-2013). His latest book is History of the Catholic Church: From the Apostolic Age to the Third Millennium (2012, Ignatius). Other books include The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life volume one and two, published by Princeton University Press, and Recovery of the Sacred (1974, 1995), his classic work on liturgy available here. James Hitchcock is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Copyright © 2004 Catholic World Report