Austrian Farmer Franz Jagerstatter

- ROBERT ROYAL

A Father Jochmann was the prison chaplain in Berlin and spent some time with Jägerstätter that day.

|

|

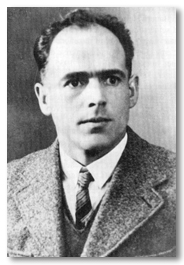

Franz Jägerstätter

|

In recent columns, we have looked at some of the Catholic martyrs under Nazism. But no account of the Nazi martyrs can leave out the remarkable story of the Austrian Franz Jägerstätter. Jägerstätters story is both simple and complex. He was born in 1907 in a village with spiritual and agricultural roots going back perhaps as far as Roman times, where everyone was a farmer. In some accounts of Jägerstätters life, he is described as a simple farmer who stubbornly refused to co-operate with the Nazis after the 1938 German Anschluss overran Austria. This is a true, but incomplete way of characterizing a man whose soul was of a quite rare kind, akin, in fact, to the great contemplatives and saints.

Jägerstätter received only a basic education at the local school, but he developed good reading and writing skills. When in his mature years he became an ardent believer, he would take time out of his demanding work on the farm to read the Bible and spiritual works. By the time he was imprisoned, he was well versed enough in Christian history and thought that this "simple farmer" was delighted to find a copy of St. John Chrysostoms sermons among the prison books.

The town myth is that Jägerstätter lived a wild life as a young man, but later "got religion." However we are to understand this, by 1936 Jägerstätter was a firm and active believer and began serving as the sexton in the local church. Around that year, he wrote to his godchild with the boldness of spiritual expression that was characteristic of him: "I can say from my own experience how painful life often is when one lives as a halfway Christian; it is more like vegetating than living." And he poignantly adds: "Since the death of Christ, almost every century has seen the persecution of Christians; there have always been heroes and martyrs who gave their lives often in horrible ways for Christ and their faith. If we hope to reach our goal some day, then we, too, must became heroes of the faith."

In the meantime, he went about his business, much like others, but with important differences. He had three children and a farm to run, but Jägerstätter did not use family needs as an excuse to deviate in the slightest from what was right. He stopped going to taverns, not because he was a teetotaler, but because he got into fights over Nazism. At the same time, he practiced charity to the poor in the village, though he was only a little better than poor himself. The usual custom in the village was to give a donation to the church sexton for his help in arranging funerals and prayer services. Jägerstätter refused them, preferring to join with the faithful rather than act as a paid official. The period of self-discipline prepared him for much more demanding sacrifices.

When the Nazis arrived, not only did he refuse collaboration with their evil intentions, he even rejected benefits from the regime in areas that had nothing to do with its racial hatreds or pagan warmongering. It must have hurt for a poor father of three to turn down the money to which he was entitled through a Nazi family assistance program. But that is what he did. And the farmer paid the price of discipleship when after a storm destroyed crops he would not take the emergency aid offered by the government.

As the Nazis organized Austria, Jägerstätter had to decide whether to allow himself to be drafted by the German army and thus collaborate with Nazism. Two seemingly good reasons were given to him, sometimes by spiritual advisers, why he should not resist. First, he was told, he had to consider his family. The other argument was that he had a responsibility to obey legitimate authorities. The political authorities were the ones liable to judgment for their decisions, not ordinary citizens. Jägerstätter rejected both arguments. In normal times, of course, obedience to authority may be required even when we disagree on certain policies. But the 1940s in Austria were not normal times: to obey for obediences sake would have been to do what Adolf Eichmann would later plead in his trial in Jerusalem he was just following orders.

The consequences of Jägerstätters position were obvious: "Everyone tells me, of course, that I should not do what I am doing because of the danger of death. I believe it is better to sacrifice ones life right away than to place oneself in the grave danger of committing sin and then dying." But he serenely decided that he could not allow himself to contribute to a regime that was immoral and anti-Catholic. Jägerstätter was sent to the prison in Linz-an-der-Donau, where Hitler and Eichmann had lived as children. According to the prison chaplain, 38 men were executed there, some for desertion, others for resistance similar to Jägerstätters (no others have been positively identified). His Way of the Cross would not be long. In May, he was transferred to a prison in Berlin. His parish priest, his wife and his lawyer all tried to change his mind. But it was useless. On Aug. 9, 1943, he accepted execution, even though he knew it would make no earthly difference to the Nazi death machine.

A Father Jochmann was the prison chaplain in Berlin and spent some time with Jägerstätter that day. He reports that the prisoner was calm and uncomplaining. He refused any religious material, even a New Testament, because, he said, "I am completely bound in inner union with the Lord, and any reading would only interrupt my communication with my God." Very few men could have made such a statement without seeming to be in denial or utterly mad. Father Jochmann later said of him: "I can say with certainty that this simple man is the only saint I have ever met in my lifetime."

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Royal, Robert. Austrian Farmer Franz Jagerstatter. Arlington Catholic Herald (2000).

Published by permission of Robert Royal and the Arlington Catholic Herald.

The Author

Robert Royal is the founder and president of the Faith & Reason Institute in Washington, D.C. and editor-in-chief of The Catholic Thing. His books include: 1492 And All That: Political Manipulations of History, Reinventing the American People: Unity and Diversity Today, The Virgin and the Dynamo: The Use and Abuse of Religion in the Environment Debate, Dante Alighieri in the Spiritual Legacy Series, The Catholic Martyrs of the Twentieth Century: A Comprehensive Global History, The Pope's Army, and The God That Did Not Fail. Dr. Royal holds a B.A. and M.A. from Brown University and a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the Catholic University of America. He has taught at Brown University, Rhode Island College, and The Catholic University of America. He received fellowships to study in Italy from the Renaissance Society of America (1977) and as a Fulbright scholar (1978). From 1980 to 1982, he served as editor-in-chief of Prospect magazine in Princeton, New Jersey.

Robert Royal is the founder and president of the Faith & Reason Institute in Washington, D.C. and editor-in-chief of The Catholic Thing. His books include: 1492 And All That: Political Manipulations of History, Reinventing the American People: Unity and Diversity Today, The Virgin and the Dynamo: The Use and Abuse of Religion in the Environment Debate, Dante Alighieri in the Spiritual Legacy Series, The Catholic Martyrs of the Twentieth Century: A Comprehensive Global History, The Pope's Army, and The God That Did Not Fail. Dr. Royal holds a B.A. and M.A. from Brown University and a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the Catholic University of America. He has taught at Brown University, Rhode Island College, and The Catholic University of America. He received fellowships to study in Italy from the Renaissance Society of America (1977) and as a Fulbright scholar (1978). From 1980 to 1982, he served as editor-in-chief of Prospect magazine in Princeton, New Jersey.