The Multicultural Ploy

- JAMES K. FITZPATRICK

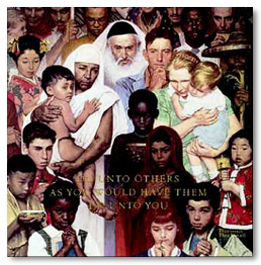

How do we prepare our children to hold to their belief in the uniquely divine origin of Christianity the Word becoming Flesh without them being guilty of the dreaded "ethnocentrism" that their teachers may well condemn? Is there any way to view Christianity as "truer" than Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism without becoming a "bigot" in the process? Is it intolerant, an insult to the people of these other religions, to insist that Jesus was the Way, the Truth, and the Life?

|

What

can parents do when faced with a classroom teacher who is committed to indoctrinating

their children into the "multicultural" view of the world, into concluding,

for example, that it is ignorant and close-minded not to see all of the world's

religions as equal, intolerant to hold that the Catholic Church is the "universal

sacrament of salvation," "united in a mysterious way to the Savior Jesus

Christ," in the words of Dominus Iesus?

How do we prepare our children to hold to their belief in the uniquely divine origin of Christianity the Word becoming Flesh without them being guilty of the dreaded "ethnocentrism" that their teachers may well condemn? Is there any way to view Christianity as "truer" than Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism without becoming a "bigot" in the process? Is it intolerant, an insult to the people of these other religions, to insist that Jesus was the Way, the Truth, and the Life?

The multiculturalists have managed to convince educational authorities that it is their mission to not only inform students about the customs and mores of other cultures, but also to free them from "judgmental" attitudes that lead them to consider non-Western cultures as somehow inferior to the Christian West. This is the unspoken premise of those who promote the "global perspective," through lessons in "values clarification."

It should be noted that there is a certain irony to all this, now that we see so much of the non-Western world struggling to adopt democratic systems of government and concepts of individual rights, to industrialize and integrate themselves with the international banking systems, to free themselves from ancient animist religious beliefs and traditional understandings of the family and the role of women in short, to Westernize themselves.

Moreover, it should not be overlooked that the movements to achieve independence from colonial rule in the non-Western world were inspired by notions of democratic self-rule, national independence, human rights and political liberty concepts that were introduced to the Third World by colonial rulers. The rhetoric of Indian liberator Mohandas Gandhi, for example, was shaped by concepts of individual and national rights that are clearly European in origin. Third World countries achieved independence by appealing to the consciences of their colonial rulers, by pointing out the hypocrisy of denying colonial subjects the very rights and freedoms that the European powers held as central elements of their Western heritage.

Europeans Living in Caves

There is a related phenomenon that deserves mention. Modern social studies textbooks routinely feel free to make allusions to the degree to which non-Western cultures were "more advanced" than Europe at certain stages of history. There will be references to how the Egyptians were building pyramids while Europeans were "living in caves"; that Arabs had developed algebra when Europeans were still working with primitive methods of making calculations; that the Chinese were wearing silk when Europeans dressed in ragged animal skins; that Incas and Aztecs were constructing magnificent temples and solar charts when Europeans were praying to trees.

The irony is manifest: Why is it permissible to praise these achievements of the non-Western world, but "ethnocentric" and "racist" to make note of the accomplishments of the Western world in religion, science, art, industrial development and philosophy what used to be routinely called the heritage of the Christian West?

But the question remains: How can a Christian child be prepared to deal with the multicultural call for understanding and broad-mindedness and an end to ethnocentrism without surrendering his or her faith in the process?

The answer is for the parent to make clear to the child the difference between an intelligent and commendable respect for cultural differences and "indifferentism." A cosmopolitan respect for non-Western societies is an admirable attribute; indifferentism is not.

Indifferentism is the notion that it is wrong-headed to cling to deeply held convictions about our own moral, ethical and religious beliefs. It argues that one religion or ethical system is as valid as another; that truth about these matters lies in the eyes of the beholder. It is an expression of a moral relativism in the international arena, the assertion that it is impossible to propose religious, ethical, artistic, or political truths in a manner that can be communicated to societies outside our own.

Is Cannibalism An Alternative Lifestyle?

American educators have introduced this multicultural message remarkably well, with considerable help from the folks in Hollywood. Over the years, I have been able to measure the impact by assigning a brief section from Montaigne's essay "On Cannibalism" to my advanced placement courses in European history. Montaigne, you will recall, was attempting to encourage a greater tolerance between Catholics and Huguenots in 16th century France by pointing out how difficult it would be to convince a cannibal, whose tribe had been practicing cannibalism without shame from time immemorial, that there was something immoral about the practice.

You could not use the Bible to make your point to the cannibal in question, since he would not concede its authority. European-defined notions of human rights would not get you very far either: his village elders used their human reason to conclude that cannibalism was entirely proper.

Needless to say, Montaigne's point was not that cannibalism was a good thing, only that it can be difficult to convince those who do not share your religious and moral background that they are in error. He was hoping that his essay would encourage Catholics and Huguenots to be patient with what they considered each other's religious shortcomings, shortcomings which both Huguenots and Catholics would find far less deplorable than cannibalism.

Almost without exception, however, in my classes, year after year, the students would go farther than Montaigne. Montaigne assumed his readers would agree that cannibalism was indefensible. It was his starting point, the catalyst for further analysis. My students were never willing to make that judgment. Instead, they would repeat the stock lines you might expect: "Cannibalism may have been true for them, even if Europeans disagreed." Or, "Even though I am personally opposed to cannibalism, that would not give me the right to impose my morality on another society. We wouldn't want them coming here and telling us how to behave. Their values are different from ours."

I am not exaggerating for emphasis. These were typical of the statements I would get in my classes over the last ten years. To be sure, the students were uncomfortable when they were saying these things. (My objective, I will admit, was to encourage them to squirm a bit in the hope that they would come to grips with the implications of the multicultural premise.) Still, they saw no alternative. They recoiled at the thought of becoming judgmental. To do so would violate the multicultural wisdom taught to them from their elementary school days and by their favorite rock stars: "Who is to say that our view of these things is right? What right do we have to condemn anyone else's values?"

In recent years I would include in the discussion the practice of female genital mutilation in certain areas of modern Africa and the killing of female infants in parts of China and India. I am happy to inform you that my students were more willing to become judgmental in these cases. But they were never able to explain why. That is the key. They could not come up with an appropriate authority to condemn these practices. They sensed that these things were wrong, but could not say why.

There are other cases where the same inconsistency can be found. If you ask modern educators if Abraham Lincoln was acting ethnocentrically when he condemned slavery in the American South, you will be greeted with impatient frowns. As you will if you ask whether those who called for military intervention against the Nazis were being insensitive to the cultural mores of Nazi Germany. The implication is that you are trying to be difficult.

Yet there is no sophistry implicit in these questions. They force one to deal with the implications of the multicultural premise. It is within bounds to ask why it is not ethnocentric arrogance to condemn Indian female infanticide or the Nazi concentration camps. It is not a satisfactory answer to say that "Killing is different," or that "Genital mutilation is different."

If we are entitled to impose our understanding of right and wrong upon other societies in these areas, we are conceding that objective truth exists, irrespective of cultural disagreements. We also open ourselves to the notion that it very well may exist in other areas as well: perceptions of God, sexual propriety, concepts of natural right and property rights, and the entire array of values and behaviors which European imperialists have been widely condemned for trying to universalize in the last century.

Readers are invited to submit questions and comments about this and other educational issues. The e-mail address for First Teachers is jkfitz42@aol.com, and the mailing address is Post Office Box 185912, Hamden, CT 06518-9997

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

James K. Fitzpatrick. "The Multicultural Ploy." The Wanderer (July 11, 2002).

This article has been reprinted with permission from the author.

The Author

James K. Fitzpatrick is a 1964 graduate of Fordham University in New York. He is the author of five books and numerous articles and reviews in a variety of scholarly journals, such as First Things, New Oxford Review, Homeschooling Today and Human Life Review. He writes two weekly columns for The Wanderer. He currently resides in Hamden, Connecticut.

Copyright © 2002 The Wanderer