Living With Dignity

- ALISON DAVIS

17 years ago I decided I could no longer face life. I wanted to die a strong wish that lasted over 10 years. If euthanasia were legal then, I would no longer be here to write this. But I have changed my outlook on life.

|

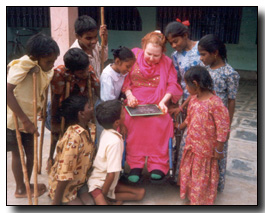

Alison

Davis

at the Ongole Center in India |

Deborah Annetts, writing in the Guardian last week, lamented the fact that a man with cancer went to Switzerland in order to end his life, and suggested that a euthanasia law with "strict legal safeguards" would be an ideal way to deal with the problems faced by people who are "suffering unbearably from an incurable illness." I have good reason to disagree. Had the sort of law she proposes been in place some 17 years ago I would not now be writing this.

I have spina bifida, emphysema and osteoporosis. I use a wheelchair full time, and suffer severe spinal pain on a daily basis. This pain is not always well controlled even with morphine. All the conditions I have are incurable, and it is very likely that my pain will get worse over time. When the pain is at its worst I cannot think or speak, and this can go on for hours, with no prospect of relief. Taking morphine often makes me feel sick, and severe nausea is an added burden.

17 years ago I decided I could no longer face life. I wanted to die — a strong wish that lasted over 10 years. During the first 5 of those years I seriously attempted suicide, by various methods (cutting my wrists, taking overdoses of painkillers with large amounts of alcohol, etc). I wanted to sleep for ever and never hurt again. On the most serious of those occasions I was taken to hospital after my friends found me and called 999. I was treated against my will in hospital, and was extremely angry with the friends who had initiated life-saving treatment.

I was of sound mind. My decision was voluntary. I had several incurable conditions, I had severe pain which could not be remedied, and I had a "settled wish." At the time some doctors thought I had only a short time to live — one suggested 6 months — but I continued to live and had a settled wish to die for about 10 years.

Had a Dutch-type euthanasia law been in place I would have requested death. Under the "strict legal safeguards" which apply there, I would have qualified for euthanasia. Criteria like these are not "safeguards" at all, despite the insistence of those who support euthanasia that they are. They just separate those who are considered "right to want to die" from those considered "wrong to want to die." Those in the latter group receive help to live. Those in the former are killed. The criteria cited as "safeguards" are simply value judgements by those who think they know what sort of person is, in effect, "better off dead."

Pro-euthanasia campaigners have sometimes suggested that I would not, in fact, have qualified for euthanasia under a Dutch model law, because I was not terminally ill, and because they claim I was "depressed." These suggestions are easily refuted. Quite apart from the doctors' (incorrect) estimation of my remaining life-span, the Dutch law does not specify that the patient must be terminally ill, only that s/he must have an incurable condition, be "suffering unbearably" and that there be no alternative way of alleviating the suffering.

Leaving aside the arrogance of those who claim the ability to gauge my mental state at a time when they did not even know of my existence, the Dutch law also does not exclude depression as a reason for allowing euthanasia. Indeed there have been cases of euthanasia in Holland in which the patient's only condition was depression. Deborah Annetts, in her Commentary, cited the aims of the VES as "we campaign for a more humane law in the UK limited to competent adults, suffering unbearably from an incurable illness who are making an informed choice." That statement also does not specify that the person must be terminally ill and not be depressed. I would qualify for euthanasia under those criteria too. Now, some seven years after the wish to die receded I still have the same disabilities and my spinal pain is equally as severe as it was when I wanted to die. What changed was my outlook on life.

I went to India with Colin Harte, my full time assistant, to visit a new project to help disabled children, little knowing that it would change my life for ever. Many of the children are so disabled they can barely manage to crawl in the dust. They are unwanted and unloved by their families, but it is true to say that they saved my life. The first time I visited the children they called me "Mummy." They hugged and loved me, and as I was playing with them, I suddenly loved them all, overwhelmingly and fiercely, as if they really were my own. When we left I said to Colin "I think I want to live." It was the first time I had thought that for over 10 years.

As a result of that visit, I founded and now run a charity called Enable (Working in India) to help those and, now, many more disabled children. "My" children have given me a reason to live. They love me overwhelmingly, just as I am. They too have incurable conditions, and many suffer much pain. But they can and do give and receive a tremendous love, which transformed my life.

Euthanasia would have robbed me of the last 17 years of my life, and it would have robbed "my" Indian children of the chance in life they now have. While the VES speak only of a right to "die with dignity" what people like me really need is help and support to live with dignity until we die naturally.

For more information on anti-euthanasia campaigns in the U.K, see Very Much Alive, a group of disabled people who oppose euthanasia, and Alert, a group campaigning against euthanasia.

You can write to the author of this piece at Alison.Davis2@btinternet.com.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Alison Davis. "Living with Dignity." The Guardian (November 10, 2002).

This article reprinted with permission from the author, Alison Davis.

The Author

Alison Davis runs Enable (Working in India), which she set up to support disabled children in South India.

During a visit to India in 1995 Alison Davis and Colin Harte visited a centre built to care for 35 disabled children in the town of Kanigiri, Andhra Pradesh State, South India, which had just been opened by Fr Gali Arulraj, an Indian priest. They were impressed by Fr Arulrajs pioneering work, and seeing that he was getting very little support, set up a charity in the UK, now called Enable (Working in India), to fund and develop his work.

With Enables support the Kanigiri Centre has grown to accommodate 75 disabled children. A second centre to accommodate a further 50 children (and with room for further growth) was opened in January 2001 in the town of Ongole, 50 miles from Kanigiri.

Copyright © 2002 The Guardian