On Flannery O'Connor, Brittany Maynard & the Eclipsing of God

- TOD WORNER

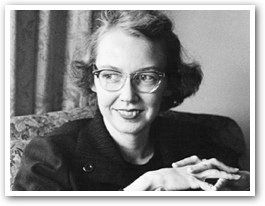

It was 1951 and she was much too young to be so sick.

Much too young. And she had her suspicions about what it was. The fevers. The drenching sweats. The profound fatigue and the joint pains — oh, the joint pains. She had her suspicions. After all, Flannery O'Connor had seen her father endure something like it before her…and he died one month into his forty-fifth year. Years later when she fully grasped that she too had the mysterious yet ravaging rheumatologic disease, systemic lupus erythematosis (commonly known as "lupus"),she wryly recalled the treatment — or rather, the lack thereof — available to her father during his final years.

Much too young. And she had her suspicions about what it was. The fevers. The drenching sweats. The profound fatigue and the joint pains — oh, the joint pains. She had her suspicions. After all, Flannery O'Connor had seen her father endure something like it before her…and he died one month into his forty-fifth year. Years later when she fully grasped that she too had the mysterious yet ravaging rheumatologic disease, systemic lupus erythematosis (commonly known as "lupus"),she wryly recalled the treatment — or rather, the lack thereof — available to her father during his final years.

"At that time, there was nothing for it but the undertaker."

Flannery loved her father. Deeply. And though she spoke little of him, a private reflection scribbled in her college notebook revealed the pain that endured years after his death,

"The reality of death has come upon us and a consciousness of the power of God has broken our complacency like a bullet in the side. A sense of the dramatic, of the tragic, of the infinite, has descended upon us, filling us with grief, but even above grief, wonder. Our plans were so beautifully laid out, ready to be carried to action, but with magnificent certainty God laid them aside and said, 'You have forgotten — mine?'"

She was much too young to be sick. Convinced she had rheumatoid arthritis, her physician knew otherwise. So did her mother. But they concealed the true diagnosis from her fearing it would devastate her. The truth would come to her from a friend, Sally Fitzgerald, on a car ride running errands in the summer of 1952.

"On the way back, on a lovely summer's afternoon, [Sally] glanced over at her passenger, wondering how she could disturb such peace; but she had made up her mind, following much inner struggle, that Flannery should finally know the true nature of her illness. At that instant, Flannery happened to mention her arthritis. 'Flannery, you don't have arthritis,' Sally said quickly. 'You have lupus.' Reacting to the sudden revelation, Flannery slowly moved her arm from the car door down into her lap, her hand visibly trembling. Sally felt her own knee shaking against the clutch, too, as she continued driving along Seventy Acre Road.

'Well, that's not good news,' Flannery said, after a few silent, charged moments. 'But I can't thank you enough for telling me…I thought I had lupus, and I thought I was going crazy. I'd a lot rather be sick than crazy.'"

- Excerpted from Flannery: A Life of Flannery O'Connor by Brad Gooch

She was much too young to be sick. Flannery O'Connor would struggle through steroids and antibiotics, transfusions and infusions, hospitalizations and bedrest. Biting pain, oppressive fatigue and distracting fogginess would be her constant companions. The vision of her father was always before her. And yet from 1952 until 1964, Flannery wrote her novels, Wise Blood and The Violent Bear It Away. She compiled a series of short stories collected in A Good Man is Hard to Find and Everything That Rises Must Converge and others. She wrote dozens and dozens of book reviews for her Catholic diocesan newspapers.

Even more, Flannery wrote letters. To friends. To family. To mentors. To aspiring writers. These letters were collected posthumously and edited by her friend, Sally Fitzgerald. The Habit of Being is an extraordinary testimony to the brilliant, witty, confident yet self-effacing, loyal, struggling yet surviving beauty that is Mary Flannery O'Connor. And in those letters she guided Alfred Corn (see my previous post, Dear Ms. Connor: On Writing Letters to Flannery), she sparred with Cecil Dawkins, and she confided in her friend, "A". And she touched me and thousands more readers to this day. What is more is that during those letters and between those letters, Flannery O'Connor, in her suffering, in her uncertainty and in her fear…was simply there. She was there to feed the peafowl at her Andalusia Farm. She was there to pick up the mail and eat breakfast. And Flannery was there for her aging mother to come late at night into her room to look upon her beautiful, yet dying child. She was there when many in our modern world might argue she didn't have to be. Her suffering, some would argue, justified her to leave it all behind. Just leave it all behind.

In 1946, at the tender age of twenty, Flannery O'Connor composed her end of a private dialogue with God. Never intended for wider circulation, this was published only recently as A Prayer Journal. In it she pleads,

"Dear God, I cannot love Thee the way I want to. You are the slim crescent of a moon that I see and my self is the earth's shadow that keeps me from seeing all the moon. The crescent is very beautiful and perhaps that is all one like I am should or could see; but what I am afraid of, dear God, is that my self shadow will grow so large that it blocks the whole moon, and that I will judge myself by the shadow that is nothing."

"I do not know you God because I am in the way. Please help me to push myself aside." Consider that again…

"My self shadow will grow so large that it blocks the whole moon."

"Please help me to push myself aside."

Shadows of self wane and the brilliant crescent of God enlarges. And in spite of loss, comes indescribable peace. In spite of trials, sweet, enduring peace.

The recent news of Brittany Maynard's young life marred by an inoperable and advanced brain tumor was deeply tragic. As was her suicide. I have taken care of patients with terminal illness and even so, I will never fully appreciate the depth of what each patient experiences and what they must grapple with. But one thing I have seen, time and again, is my patient's grasp that something larger than themselves occurring. This is not simply the feeling of being victim to an overwhelming illness. But rather, it is their keen sense of the larger narrative of life. I have been blessed to see, in the midst of sadness, fear and pain (which can be managed quite sensitively through my efforts and those of gifted practitioners in palliative care and hospice) the emergence of a surreal clarity sharpened and sweetened by an estranged relationship made right, a hand held for just one moment longer or a priest's anointing that unfurrows many brows. By slipping into life's end without actively ending it, there is time afforded for the most unforeseen holy moments and delicate gestures. It is in these very sacred — even sacramental — moments that selves have been pushed aside to make room for God. Shadows of self wane and the brilliant crescent of God enlarges. And in spite of loss, comes indescribable peace. In spite of trials, sweet, enduring peace.

Again, Flannery wrote,

"Our plans were so beautifully laid out, ready to be carried to action, but with magnificent certainty God laid them aside and said, 'You have forgotten — mine?'"

Perhaps, just perhaps, we are part of a larger narrative. And perhaps we are called to profound patience and deep faith in an unfolding world of frustrating mystery and the sweetest grace. May we always seek to enlarge God in our lives. And always avoid eclipsing him.

May God rest the souls of Flannery O'Connor and Brittany Maynard.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Tod Worner. "On Flannery O’Connor, Brittany Maynard & the Eclipsing of God." A Catholic Thinker (November 7, 2014).

Tod Worner. "On Flannery O’Connor, Brittany Maynard & the Eclipsing of God." A Catholic Thinker (November 7, 2014).

Reprinted with permission from the author, Tod Worner.