They Brought Their Sick to Him

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

Who can hold out against the father of lies, without the grace of God?

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

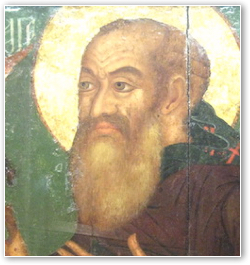

Saint Basil the Great

Saint Basil the Great329 or 330-37

The preacher stands before the crowds, sparing no one's complacency. "You array your bodies and your homes with luxury," he cries, "but the most glorious creature that God ever made, your fellow man, you allow to go in tatters! Hear what the rich man in the parable says. He will pull down his barns and erect a great granary, a monument to his pride, and then he will live at his ease. Fool! That very night the Lord will require of him his life."

His name is Basil, "king." That name is both apt and deeply ironic. You'd never look upon his spare form and think of royalty. For clothing he owns but a cloak and sandals. He lives mainly on bread and water. But by his very poverty and piety he gains an authority over his congregation that kings can never know, in all their regalia and their trailing retinues of favorites and flatterers.

For Basil, poverty was not merely a social problem, to be addressed by distant and impersonal measures. The poor man who borrows as a last resort, and who then scrambles under his bed when he hears his creditor's knock on the door — that is your brother. The boy who survives in the street by stealing, he is your own son. Other preachers might be content with general principles of Christian charity. Not Basil.

The Mass ends, and the people return to their homes in the swarming city of Caesarea, named for the emperor Augustus on his death in A.D. 14. For the Roman armies had reduced the vast high plateau of Cappadocia to the liberty of a Roman province. To the north, the great River Halys bends on its course to the Black Sea. To the south, a great snowy volcanic cone, Mount Argaeus, rises more than a mile and a half above the surrounding country.

If you are poor or sick in this land, so much the worse for you. It's not the honey-sweet land of the Greek isles, near to the swell of the wine-dark sea. It is far inland, brutally hot in summer, icy in winter. The harvests have been poor, and the people are hungry. And the armies of the Arian emperor Valens have been doing bloody work. In that place, at that time, Saint Basil came to a decision.

"We need a new city," he said.

Theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven

"Beggars and strangers come from Zeus," went the old Greek proverb, for the gods would come down to put arrogant men to the test, showing up at their gates with a walking stick and in rags. There was no sense that the poor should be loved. Hospitality is one thing, but love is quite another. Maybe we can translate the proverb in this way: "People who cringe and who don't belong here might be sent by that master of justice — and cunning. We'd better watch out."

But Jesus the journeying preacher from dusty Palestine had changed all that for ever, at least for those who profess to follow him. Blessed are the poor, he said, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. And if you're too rich to beg, your well-laden camel might find entry into its gates a bit tight. The pagans understood, deep down, that there was something at least uneasy about riches. Menelaus, in the Odyssey, is a very rich man — but not much of a man. Socrates didn't own much, but he did cadge dinners at the homes of his rich young patrons. Yes, the pagans understood it, somewhere, somehow, just as pagans nowadays understand it. Such understanding is cheap.

Basil had long been doing the work of Christian charity. Here's how his dear friend, Saint Gregory of Nazianzen, described it:

He gathered together the victims of the famine with some who were but slightly recovering from it, men and women, infants, old men, every age which was in distress, and obtaining contributions of all sorts of food which can relieve famine, set before them basins of soup and such meat as was found preserved among us, on which the poor live. Then, imitating the ministry of Christ, who, girded with a towel, did not disdain to wash the disciples' feet, using for this purpose the aid of his own servants, and also of his fellow servants, he attended to the bodies and souls of those who needed it, combining personal respect with the supply of their necessity, and so giving them a double relief.

See How They Love One Another!

How to bring personal care to the thousands who needed it — that was the problem. Nothing like it had been done in the history of the world. A new city indeed was needed.

So Basil acquired some land outside of Caesarea, and there he began to build.

The ancients had no true hospitals for everyone. The Romans had built infirmaries for veteran soldiers, or for the valued slaves of the wealthy, but in general, if you were a sick man and had no patron, you were out of luck. You might go to the temple of the healer-god, Asclepius, and pray that he might lift the curse from your body. That was about it.

The apostate emperor Julian famously wrote, in envy, that the Christians put his fellow pagans to shame, because they did a better job taking care of pagans than the pagans themselves did!

Christians, however, had been commanded to tend the sick, in body and spirit, and this duty fell most of all upon the bishop, the priests, and in particular the servants, that is, the deacons. The bishop's very home was to be open to all travelers. That was the command, and the practice lived up to it. The apostate emperor Julian famously wrote, in envy, that the Christians put his fellow pagans to shame, because they did a better job taking care of pagans than the pagans themselves did!

The Christians did so in homage to Christ the Healer, of whom Asclepius was but a shadowy allegory, as Saint Justin had said almost 200 years before. Jesus had gone about Galilee and Judea healing the sick, and his disciples and Apostles would do the same, and if someone was dying, said Saint James, then the priest should lay his hands upon him and anoint him, and confer healing, if not of the body, then of the sin-sick soul. We remember the Samaritan in Jesus' parable, who went down into the ditch by the roadside to take up the man who had fallen among thieves, to clean his flesh with wine and oil, and to bind up his wounds with his own hands.

Hands — not mere money, but hands.

The City Rises

Basil called it the Ptochotrephion, the House for Care of the Poor, but others soon called it the Basiliad, or simply the New City.

Imagine separate buildings for those who were afflicted by the plague, for those who were recovering, for the lepers whom no self-respecting pagan would go near, for women in childbirth, and for people nearly starved with the famine.

Imagine separate buildings for those who were afflicted by the plague, for those who were recovering, for the lepers whom no self-respecting pagan would go near, for women in childbirth, and for people nearly starved with the famine. Imagine hospices for travelers, and chapels for all of us wayfarers on the road to the last things.

Imagine schools — especially shops where a young man with no money and no prospects might learn a gainful trade, to be a mason, a tanner, a potter, a carpenter. Imagine monks, hundreds of them, for whom this entire city is their monastery. One monk washes the purulent sores of a dying man. Another is showing a boy how not to gouge the wood with the plane. Another plies his hoe in a large field of vegetables. Another brings the Body of Christ to a child too sick to move. Another digs a grave. All of them are working and praying.

In his eulogy for Basil's requiem Mass, Saint Gregory Nazianzen praised this wonder of love, greater in real glory than "seven-gated Thebes...and the pyramids, and the immeasurable bronze of the Colossus," and all those other wonders of the world, which gained their founders nothing but a little brief fame. "Go forth a little way from Caesarea," he said, "and behold the new city, the storehouse of piety, the common treasury of the wealthy, in which the superfluities of their wealth, yes, and even their necessaries, are stored, in consequence of [Basil's] exhortations, freed from the power of the moth, no longer gladdening the eyes of the thief, and escaping both the emulation of envy, and the corruption of time: where disease is regarded in a religious light, and disaster is thought a blessing, and sympathy is put to the test." Even the lepers are welcome there, "composers of piteous songs, if any of them have their voice still left to them."

If Only We Had One Now

Such were the hospitals, which the Church bequeathed to the world. And now our sick are cared for in buildings twenty stories high, with medicines and machines that Saint Basil could never have imagined. Yet I have a fond hope that someday, amid the un-music of monitors, within the icy white walls, beyond the reach of accountants and executive officers, something of the human, something of the love that touches the soul of man, will return. We all must die, medicine or no. It would be a good thing at least to die among friends, strengthened and cheered by good men of God, and given that last sweet nourishment for the journey; to be with Christ, to receive Christ, on the way to Christ.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "They Brought Their Sick to Him." Magnificat (April, 2016).

Anthony Esolen. "They Brought Their Sick to Him." Magnificat (April, 2016).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2016 Magnificat