The Catholic Church's best-kept secret

- DAMIAN THOMPSON

Earlier this year I paid several visits to a hospital in the Home Counties to see someone very close to me. Then an angel arrived at the bedside.

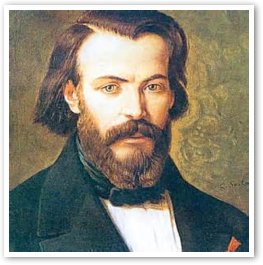

Blessed Frédéric Ozanam

Blessed Frédéric Ozanam1813-1853

Thank goodness the outcome was a full recovery — but there were some harrowing moments for which nothing in my previous life had prepared me. The slightly stilted friendliness of the NHS staff and the fresh pastel paint on the walls were intended to take the edge off the ordeal, but it was all horribly disorientating (the more so because doctors are called by their first names, so at times I didn't know who I was talking to).

The first trip was the most awful, because the person I was visiting was in tremendous pain and, despite being formidably brave, could not conceal it. No one could have. My own attempts at cheerfulness sounded embarrassingly hollow. In the end I gave up and stared at the rain beating against the window.

But then an angel arrived at the bedside. Now, that may seem rather a banal and sentimental description of a middle-aged lady from the local Catholic parish, but the effect was almost supernatural. Angela (not her real name) exuded compassion, cheerfulness and — most welcome of all — a relaxed air that produced a smile from the patient and unclenched my fists. She knew how to visit the sick, which is not just a corporal act of mercy but also a skill that demands more than good nature. Angela had worked out exactly what tone to strike, what questions to ask, how to negotiate with the hospital staff and how to distract a sick person from unremitting pain.

She was from the Society of St Vincent de Paul — the SVP. Throughout my childhood I'd heard priests mention the SVP during the notices at Mass and never given the outfit a second's thought. Members visited old people's homes and hospitals, that much I knew, and how nice of them. My grandparents had belonged to it, possibly on both sides of the family. Also my parents — maybe: as a youth I displayed a stroppy lack of interest in any of their church activities.

So there I was in the hospital thinking: gosh, the SVP are lucky to have the amazing Angela on their books. But then, in the weeks that followed, she was replaced by Gerry (again not his real name), a retired Scottish guy. And he was every bit as amazing. He had a pink, glowing complexion and, like Angela, maintained a low-key cheerfulness that seemed both spontaneous and expertly judged. He visited every day and untangled all sorts of little problems. Even an old cynic like me could recognise Christian love in practice. By that I don't mean that non-Christians can't display the same intensity of compassion, but that both Angela and Gerry were patently motivated by their Catholic faith. Neither brought up the subject of God while I was there, but they didn't need to.

Eventually I became curious about the SVP. So last week I read a little book about the founder of the Society, whom I vaguely remembered wasn't St Vincent de Paul (1581-1660) but a Frenchman of a very different era: Frédéric Ozanam, a married professor of foreign literature at the Sorbonne who died at the age of 40 in 1853. He was beatified in 1997, though that was news to me.

Ozanam lived his life amid religious and political turmoil. Despite the restoration of the monarchy after Napoleon, the intellectual climate in France became dogmatically anti-clerical. Catholicism did not go into decline, however. It was adopted with new fervency by sections of the middle class, who wanted the Church to reach out to workers in order to quell revolutionary passion.

Even an old cynic like me could recognise Christian love in practice.

Ozanam was, by the standards of the day, a liberal. He didn't dislike Jews or Protestants. He organised "conferences" of Catholic scholars and businessmen who ministered to the suffering. His motto was: "Beware of discouragement; it is the death of the soul." By 1848 nearly 10,000 people belonged to these conferences, which became the Society of St Vincent de Paul. The SVP believed in social justice, if not yet in social equality. Ozanam saw his role as standing between the "opposing armies" of industrialists and workers. "If we cannot stop them, at least we can lessen the shock. And being young and middle-class makes it easier for us to be the mediators that our Christian identity makes incumbent on us." He campaigned to restrict working hours in factories.

These are the roots of the Catholic social teaching that bore fruit, many years after Ozanam's death, in the encyclical Rerum Novarum. But I'm equally interested in Blessed Frédéric's insight into the psychological dimensions of poverty, sickness and old age. "A friendly conversation can elicit the secrets of a desolate heart," he wrote. Today, alleviating the pain of loneliness is at the heart of the Vincentian mission; its members are trained to identify those people most in need of the unobtrusive gift of companionship.

I have spent many years writing about the Catholic Church: its battles with secularism, its internal disputes and, inevitably, the scandals it brought upon itself. But not one of my articles made mention of the SVP, which in England and Wales alone makes more than half a million visits a year to vulnerable people in their communities. That statistic is remarkable — but even more special is the self-effacing yet unambiguously Catholic ethos of the SVP. That ethos inspires and equips ordinary people to perform extraordinary acts of kindness in countries all over the world. It's one of the things that makes the Church catholic; it's as much a part of the fabric of the faith as any cathedral or liturgy. In a way, it is a liturgy. And, even though members of my own family had been devoted to the SVP, I ignored it — until the moment when Angela came sailing into that hospital ward with a miraculously sunny smile on her face.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Damian Thompson. "The Catholic Church's best-kept secret." The Catholic Herald (July 4, 2014).

Reprinted with permission of The Catholic Herald, the UK's leading traditionalist weekly. The Catholic Herald serves 65,000+ mass-attenders and much of the clergy every Sunday. It provides readers with in-depth news coverage, rigorous analysis of the Faith, spiritual reflection, features and comment by some of our sharpest Catholic thinkers, and studies the path taken by the Church in Britain and Ireland today

Subscribe to the The Catholic Herald here.

The Author

Damian Thompson is a non-executive director at Catholic Herald Ltd, as well as a regular contributor and advisor on editorial matters. As well he is editor of Telegraph Blogs and a columnist for the Daily Telegraph. He was once described by The Church Times as a "blood-crazed ferret". He is on Twitter as HolySmoke. His latest book is The Fix: How addiction is taking over your world. He also writes about classical music for The Spectator.

Copyright © 2014 The Catholic Herald