The "Black Gown" and What Could Have Been

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

Had America followed the lead of Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, great good would have come of it, and many evils — war, the theft of Indian lands, perfidy, mutual hatred, and the moral collapse that awaits a defeated people under patronage — might never have been.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

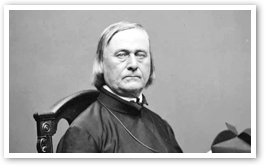

Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J.

Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J.1801-1873

There's a small town in South Dakota named De Smet, nicknamed the "Little Town on the Prairie," after the pleasant children's books written by Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter Rose. Every summer the residents of De Smet hold a pageant for tourists in honor of the Wilders. But they don't seem to hold a pageant to honor the man for whom their town is named, the Jesuit priest Pierre-Jean De Smet, one of the most remarkable missionaries in the history of the Church. That's unfortunate, since Father De Smet was a pattern of courage and Christian charity. Had America followed his lead, great good would have come of it, and many evils — war, the theft of Indian lands, perfidy, mutual hatred, and the moral collapse that awaits a defeated people under patronage — might never have been.

Let's go then to the Rocky Mountains, near the source of the Missouri River. It's the summer of 1840, and Father De Smet, thirty-nine years old, with considerable experience as a missionary, has come to meet the chief of the Snake Indians. It's a meeting that the chief had long desired. Indian tribes from as far away as the Columbia River had sent emissaries to Saint Louis, to ask for a "Black Gown" to come among them and teach them the Christian faith that they had heard about from Iroquois converts long before. Iroquois converts — that shouldn't surprise us, since the French in Canada had no foolish presuppositions about race, and many of the French and the Indians married and raised Catholic children.

Two thousand men, women, and children have come to meet the Black Gown and to be taught. Father De Smet gathered them for night prayers, teaching them in French, with an interpreter. He taught them the Our Father, the Hail Mary, the Creed, and the Acts of Faith, Hope, Charity, and Contrition. Then he showed them a silver medal, a prize for the first person who could recite the prayers by memory. "That medal is mine," said the Chief, and repeated the prayers flawlessly.

The Chief became a Christian father to his people. So Father De Smet writes to his superior:

Every morning, at the break of day, the old chief is the first on horseback and goes round the camp from lodge to lodge. Now my children," he exclaims, "it is time to rise; let the first thoughts of your hearts be for the Great Spirit; say that you love him, and beg of him to be merciful unto you. Make haste, our Father will soon ring the bell; open your ears to listen, and your hearts to receive the words of his mouth."Then, if he has perceived any disorderly act on the preceding day, or if he has received unfavorable reports from the other chiefs, he gives them a fatherly admonition. Who would not think that this could only be found in a well ordered and religious community, and yet it is among Indians in the defiles and vallies of the Rocky Mountains! You have no idea of the eagerness they showed to receive religious instruction. I explained the Christian doctrine four times a day, and nevertheless my lodge was filled, the whole day, with people eager to hear more.

Father De Smet had the Pentecostal gift of understanding the language of the heart. He could translate the faith into Indian idiom, walking in their moccasins, and hearing their expressions of faith accordingly. So when he continued his travels through dangerous territory and reached the fort at the head of the Yellowstone, the Chief said to him, "The Great Spirit has his Manitoos; he has sent them to take care of your steps and to trouble the enemies that would have been a nuisance to you." De Smet's comment is revealing: "A Christian would have said: Angelis suis mandavit de te, ut custodiant te in omnibus viis tuis — he commanded his angels concerning thee, that they should guard thee in all thy ways." The Indians saw in Father De Smet a model of godly manhood. He was courageous, traveling in person to speak to the most sanguinary tribes, like the Blackfoot. He was tireless, traveling more than 180,000 miles, almost all after he had turned forty, on behalf of the spiritual and social welfare of the Indians. He met men as a man; he endured the privations that his guides endured; he sat with chiefs and smoked the peace-pipe; he ate with gratitude what was put before him.

Father De Smet had the Pentecostal gift of understanding the language of the heart.

He was a man of profound prayer. The Indians saw that before he took food, he turned his hands to heaven to "speak to the Great Spirit" Thousands at a time listened in silence as he spoke of Jesus.

His integrity was unshakeable. Once, when he'd returned to his mission at Council Bluffs, he learned that his spiritual children the Santees had raided their neighbors the Pottawatomies. He rebuked them: "I showed them the injustice of attacking a peaceable nation without being provoked; the dreadful consequences of the Pottawatomies' revenge, that might end in the extinction of their tribe. I was requested to be once more the mediator, and they told me that they had resolved to bury the tomahawk forever."

He did not patronize the Indians. Of the weakling Snakes, so called by their neighbors because they burrowed into rocks and lived like reptiles, eating grasshoppers and ants, he wrote that "there is not, perhaps, in the whole world, a people in a deeper state of wretchedness and corruption." That made him the more eager to bring them the Gospel, to give them hope of a better life to come.

Most of all the Indians honored Father De Smet because he was their advocate before God and man. In 1843, a few years after De Smet's first trek to the northwest, the editor of his fascinating letters said this:

Many of these Indian notions actually thirst after the waters of life — sigh for the day when the real "Long Gown" is to appear among them, and even send messengers thousands of miles to hasten his coming. Such longing after God's holy truth, while it shames our colder piety, should also enflame every heart to pray fervently that laborers may be found for this vast vineyard — and open every hand to aid the holy, self-devoted men, who, leaving home and friends and country, have buried themselves in these wilds with their beloved Indians, to live for them and God.... To aid them in this philanthropic object is our sacred duty as men, as Americans, as Christians. It is at least one method of atonement for the countless wrongs which these unfortunate races have received from the whites.

When those words were written, Geronimo, Sitting Bull, and Chief Joseph were all boys. The "countless wrongs" and the animosity between the Indians and the white settlers would not end for another seventy years. Father De Smet himself wrote these words in 1841, regarding the "savagery" of the peaceful and honorable Flathead tribe:

We have been too long erroneously accustomed to judge of all the savages by the Indians on the frontiers, who hove learned the vices of the whites. And even with respect to the latter, instead of treating them with disdain, it would perhaps be more just not to reproach them with a degradation, of which the example has been given them, and which has been promoted by selfish and deplorable cupidity.

Such clear-minded fairness explains the trust that the tribes from Missouri all the way to British Columbia placed in their honored "Black Gown." The leaders in Washington knew it When the Sioux in 1862 were going to war against the white settlers to avenge themselves for stolen lands and broken treaties, whom could President Lincoln send, at the onset of the Civil War? Father De Smet alone among all the white men in America could make the journey to speak to the Indians. Along the way he heard the testimonies of thousands of Indians, so that when he learned that the government was planning an attack, he refused to give it his sanction and returned to Saint Louis. By 1868 things had gotten so bad that the government again appealed to De Smet, and this time he met Sitting Bull and persuaded him to agree to the Laramie Treaty.

Such clear-minded fairness explains the trust that the tribes from Missouri all the way to British Columbia placed in their honored "Black Gown."

Think of that — the government of the United States, with all its wealth and soldiers, having no one to turn to but one man, a priest of the hated Jesuit Order.

An impressive scene, but not so moving nor so significant as what Father De Smet did to bring the Indians to a love of the Lord. Here I'll end with another scene, among the Crow tribe east of the Cascades. Forty braves thronged about the priest when he arrived, crying, "Black Gown, Black Gown!" and carrying him on their shoulders. They brought their sick to him, and he prayed, but he told them that only God is the true Healer, and that God will punish people who adopt wicked ways, to teach them, to call them to turn their hearts toward him. For the Crows were thieves and worse.

Then the orator of the tribe stood up. "Black Gown," said he, "I understand you. You have said what is true. Your words have passed from my ears into my heart — I wish all could comprehend them." And he turned to his fellows, saying, "Yes, Crows, the Black Gown has said what is true. We are dogs, for we live like dogs. Let us change our lives and our children will live."

It's a message that many more Americans than the Crows needed to hear — and still do.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: The "Black Gown" and What Could Have Been." Magnificat (February, 2015): 203-207.

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: The "Black Gown" and What Could Have Been." Magnificat (February, 2015): 203-207.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2015 Magnificat