Pennefather heeds her calling

- JACK WILKINSON

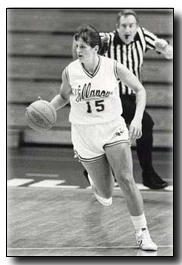

Once upon a lifetime ago, Shelly Pennefather was the sweetest of shooting stars, an All-American at Villanova and the 1987 national player of the year. Since 1991, she has lived here, in the Poor Clare Monastery, at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac in a very modest middle-class neighborhood.

|

Shelley

Pennefather |

Pennefather has taken her vows and the name Sister Rose Marie of the Queen of Angels. She renounced her worldly life, including a six-figure salary as a professional basketball star in Japan, to answer her true calling: To serve God as a cloistered Poor Clare nun.

When the NCAA Women's Final Four begins in Atlanta today, it's unlikely Sister Rose will be aware of the Duke-Tennessee and UConn-Texas semifinal pairings. It's unlikely she knows how close her alma mater came to reaching its first Final Four. Not even after a visitor to the monastery last weekend left a handwritten prayer request in a wooden box inside the cloister's front door:

Please pray for Harry Perretta and his Villanova basketball team when they play Tennessee Monday night in Knoxville in the NCAA Mideast Regional final.

The visitor, a Catholic, meant no disrespect, hoping only that another nun might find it in her heart to inform Sister Rose Marie. Yet the Colettine Poor Clares are one of Catholicism's most austere orders. They sleep no longer than four hours at a time, eat one full meal a day and don't use phones, TVs, radios or any publications except religious texts. They sleep on a bed of straw; they're barefoot except for an hour each day, when they don sandals to walk into the courtyard, where they're allowed to converse with each other.

Poor Clares have little, if any, interaction with the outside world. During Lent, the order has virtually no contact at all. So when Sister Rose Marie spends this Sunday as she does every day primarily in prayer and meditation she'll probably be blissfully unaware of the Final Four semis. She probably doesn't even know the outcome, or significance, of last month's Big East women's championship game, when Villanova upset UConn 52-48 and ended the Huskies' NCAA-record 70-game winning streak.

"I would say she doesn't," said Perretta, who coached Pennefather and still calls her "the best all-around player I've ever seen." "Well, actually, she might know. I called the monastery and left a message on the answering machine: 'We beat UConn and won the Big East.' The problem is, it's Lent. I don't know if Mother [Superior] told her."

Even if the Mother Abbess conveyed Perretta's message, Villanova associate athletics director Lynn Tighe isn't sure her old friend comprehended it. "It won't mean anything to her," said Tighe, Pennefather's freshman roommate at Villanova and teammate from 1983-87. "She won two Big East championships, our junior and senior years. [Upsetting UConn] is a great accomplishment, but she would have no understanding of the magnitude of that. It's the biggest win in the program's history, but she wouldn't understand that. Back when we played, we never lost to Connecticut."

Shelly Pennefather's mother, Mary Jane, has turned down interview requests. So have Shelly's six siblings. Mary Jane, a widow, is a private, devout woman whose children grew up in a house without a TV, prayed the rosary nightly and still honor their mother's wishes. One interview request came from ESPN, which wanted to do a 20-minute feature on Shelly to air during the Women's Final Four. Mary Jane called Perretta on March 11 to turn down that request.

"OK," Perretta told Mary Jane Pennefather. "I'm on the [team] bus, going to play for the Big East championship." Oblivious to this, Pennefather told Perretta she would say the rosary for the Wildcats and call the monastery to ask the Poor Clare nuns to pray for 'Nova.

"And then I get off the phone, and we go and win one of the biggest games of all time," Perretta said. "It's just weird. The only time she could've gotten me on my cellphone was then."

'She was the best all-around player'

When Harry met Shelly, he had a full head of hair, not a comb-over. She had a heavenly jumpshot, one honed by her late father, Mike, a jumper so pure and accurate, it helped make Pennefather one of the top five high school prospects in the country. By the time she graduated from Villanova, Pennefather had scored 2,408 points (still the school record for male or female players) and grabbed 1,171 rebounds (still the women's mark).

As Don DiCarlo, Villanova's longtime facilities coordinator, told Alex Wolff (author of "Big Game, Small World: A Basketball Adventure"), "If my life depended on one 15-footer, I'd want Shelly to take it."

"She could play guard, forward, center," Perretta said of his 6-foot-1 star. "She was intelligent, could shoot, handle the ball, everything. She wasn't the best forward, or center, or guard. But she was the best all-around player."

She was also Perretta's ticket to the trip of a lifetime: the 1987 Wade Trophy player of the year presentation in Las Vegas. "All my life, I dreamed of going to Vegas, and she got me there. Forget the Wade Trophy," Perretta said, chuckling. "She got me to Vegas." Once there, he went to the racing book; Pennefather, given $100 in tickets by her hosts to spend at Circus Circus, won dozens of stuffed animals at basketball arcade games and handed them out on the Strip to children.

At Villanova, Harry and Shelly sometimes went to the racetrack together. At Liberty Bell and Philadelphia Park, the player would help the coach pick the ponies. Pennefeather, an education major with a concentration in math, loved fiddling with numbers. That talent also came in handy at casinos in Atlantic City, where Perretta sometimes played blackjack while Pennefather counted cards. Years later, Perretta joked that, "Sister Rose is the only cloistered nun in captivity who could handicap horses and count cards."

Tighe, Pennefather's point guard for four seasons, remembers her freshman roommate who loved to watch films on TV in their dorm room, especially "The Sound of Music."

"On bus rides, she'd get everybody to break into song," Tighe said. "She knew the lyrics to every song."

The basketball star who would become a nun was singing about Sister Maria, who would forsake the nunnery to marry Captain Von Trapp.

"It is kind of ironic," Tighe said. "No chance she's leaving, though. Trust me."

Her faith was evident

At Villanova, Pennefather attended mass daily and was very spiritual. "She didn't hide that at all," Tighe said. "It didn't surprise any of us that she was going to be a nun. It just took us all aback that she was going into a cloister."

Pennefather's faith was evident at the 1987 Kodak All-America team banquet in Austin, Texas. As a publicity shot for her senior season, Villanova had Pennefather pose in a white tuxedo, with top hat and cane, standing beside a limousine and beneath a theater marquee bearing her name. In Austin, she wore a simple navy blue suit and told her fellow All-Americans, "I only hope that with the talent each one of us has received, that we never shame the God who gave it to us. . . . Thank you, and God bless you."

Her decision to quit basketball followed three seasons of stardom in Japan. With no WNBA in 1987, Pennefather signed with the Nippon Express. She spent much time alone in Japan, time for reading and introspection, and studying Japanese. She went to daily 6 a.m. mass. "That was where she got the calling to the cloister," Perretta said.

Pennefather is called

By 1991, Pennefather was earning $100,000 a season and could have signed a new contract worth nearly $200,000 a year. Yet during each of her three offseasons, she had returned to the United States and honored a personal vow by working for a month with the Missionaries of Charity, Mother Teresa's order of nuns. For parts of three summers, Pennefather worked in a soup kitchen in Norristown, Pa. She even met Mother Teresa and Mother Teresa's personal confessor, Father John Hardon.

It was Father Hardon's name that Pennefather uttered when she rang the doorbell at the monastery in 1991. The door opened. As Pennefather's late father told Alex Wolff in 1997, "It was as if someone asked you, 'Who said you could play basketball?' And you could answer, 'John Wooden.'"

Pennefather became a novice at the cloister. Her friends and Villanova teammates struggled with her decision. At first, many wept. "Traumatic," Perretta called it. "I said, 'Why do you have to hide?'"

"It was hard," he said. "I don't want to say it was like someone dying, but you're not going to see them anymore. It's like someone says, 'I'm going to Mars.'"

Tighe asked Pennefather, "Why are you doing that? I'm glad you're becoming a nun. But there's so many opportunities out there to teach and coach and influence kids' lives."

"She said, 'Lynn, I would never choose this for myself. This is what I was called to do,'" Tighe recalled. "You can't argue with that. I don't know the strength of that calling. You say, 'OK, good luck to you.'"

Visiting the monastery

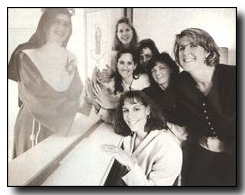

|

Sister Rose Marie of the Queen of Angels and friends |

On June 6, 1997, six years after entering the monastery as a novice and shortly before the WNBA's birth, Sister Rose took her vows as a Poor Clare nun. A crown of thorns was placed on her head, a band bearing the likeness of Jesus Christ slipped on her finger. For just the second time since she'd come to the monastery, her family was allowed to embrace Sister Rose on the altar in the small, painted-cinderblock public chapel. Their next embrace will come in 2019, when she celebrates her vows.

Mary Jane Pennefather and her children including Therese, who played at Villanova from 1997-2000 attend mass periodically at the monastery. As Sister Rose receives holy communion they catch a brief glimpse of her through a Dutch door, which opens to the nuns' choir behind the altar. Because Sister Rose is 6-foot-1, the wall behind the altar was topped by several panels of beveled glass. The "Pennefather clouds," as they're called in the cloister, shield Sister Rose from public view.

The Pennefather family is permitted to visit her three times a year. Perretta cajoled the Mother Superior, who allows him to visit Sister Rose each June. They talk for an hour, a screen separating them, as in a confessional booth. By then, Perretta has unloaded his mini-van, laden with hundreds of dollars of provisions: canned soup, crackers, Ramen noodles, all food stuffs he has brought from Philadelphia. Here, he buys perishable items: fresh fruit, frozen pizzas and fish sticks, cheeses. One year, the nuns wanted flavored seltzer water, another time chewing gum. Perretta always brings Sister Rose's favorite treat: Reese's Peanut Butter Cups, normally a no-no in a place where a meal can consist of a biscuit, a piece of fruit and sliced cheese.

"We talk about normal stuff," Perretta said, "what's going on with me, what's going on with her. All our different friends. We always used to talk a lot when she played for me."

When Perretta's first marriage was annulled, his star player helped him through his grief. Later, Sister Rose prayed her coach would find the perfect wife. Helen Moskinen, who once played for Perretta, and Harry were married in 1997 and have two sons.

'I was in the presence of great people'

Perretta's visits are often illuminating for Sister Rose. "What's that?" she once wondered when he got a phone call. She had no idea what a cellphone was. The Internet? Also a mystery. "There's a professional league?" Sister Rose asked when Perretta first told her about the WNBA.

"This year," he said, "we'll talk about the war."

Tighe is permitted to visit Sister Rose each October.

"I believe she's really happy, and she's doing what she was called to do. We should all be so happy," said Tighe, who occasionally has feelings of personal loss. "Some days, I feel like I've lost my good friend because you can't pick up the phone and call her. But there's no doubt in my mind that she's my friend, because she prays for me each day. I don't know that my other friends do that!" She laughed. "But I'm absolutely certain she does, and there's something pretty special about that."

What has most impressed Perretta about Sister Rose and her fellow Poor Clares is "how witty they are. How intelligent, how they laugh," he said. "I feel like all my buddies are in there. They know me, they know my children's names. The place has an aura, where people are doing things and ask nothing of anybody.

"When I leave there, I feel like I was in the presence of great people," Perretta said. "It rejuvenates me every year. It makes me feel like there's a better place."

There is, of course. A place as heavenly as the jumpers Shelly Pennefather once launched, a place Sister Rose can only imagine.

"We talked about dying once," Perretta recalled. "She said, 'I embrace death.' I said, 'Well, before I go, I'd like to go to Vegas four or five more times.'"

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Jack Wilkinson, "Pennefather heeds her calling." Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 6, 2003.

Reprinted with permission of the author.

The Author

Jack Wilkinson is a general assignment writer in sports for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Jack and his wife attend Sacred Heart Catholic Church in downtown Atlanta where they sing in the ten o'clock choir.

Copyright © 2003 Atlanta Journal-Constitution